Meanwhile, on the website of the Citadel Inn we can read that it incarnates “a revival of royal hospitality” and the “majestic traditions” of Austro-Hungarian “authentic imperial luxury.” In the last few years, whenever there has been building work around here, or trenches have been dug for pipes and cables, the workmen have found human remains. During the war, what is now the hotel was known as the “Tower of Death.”

15.

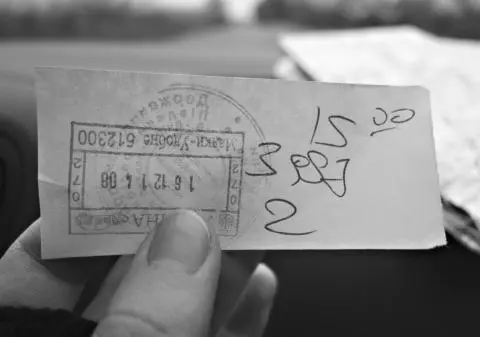

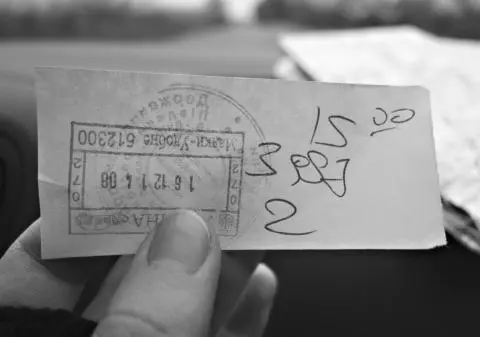

The Bessarabian Ticket

Ticket to transit across Moldova to get to Bessarabia. Mayaki, December 2014.

You need a ticket to go to Ukrainian Bessarabia. You leave Odessa, cross the bridge over the Dniester River, and ten minutes’ drive down the road arrive at a Ukrainian border post. There they give you a slip of paper with some stamps on it. The border guard writes down on the slip how many people are in your car and the time, and tells you to drive on and not to stop. For the next 7.7 kilometers you are in Moldova, or sort of. You don’t pass a Moldovan border post unless you turn off at a junction, and a few minutes later you arrive at another Ukrainian one.

“Why did you stop?” demanded the policeman.

“To buy apples.”

“You are not allowed to do that.”

“How did you know we had stopped?”

“Because I can see how long it took you to get here.”

This is the way the Soviets drew the border. Now the road is under Ukrainian jurisdiction but the woman who sells apples from bright red buckets on the side of the road is in Moldova. If you stepped off the road to buy them, you entered Moldova illegally.

Even most Ukrainians don’t know much about Bessarabia. It is not a part of their country that looms large in their history or imagination. Politically, geographically and ethnically it is something of an anomaly. It is a kind of footnote, albeit home to more than half a million people. Sometimes they refer to it as an “appendix.” And they mean that in a literal sense. Many don’t even seem to know why it is really part of Ukraine. It hangs off the bottom of its body politic and, as Ukraine went to war, some of its people, and those in Moscow planning the destruction of Ukraine, wondered if a quick surgical operation would suffice to extract it from the country.

Look at modern histories and accounts of Ukraine, and Bessarabia barely rates a mention. Maybe this is because historically there were not so many Ukrainians or Russians here, but I suspect that it is because it doesn’t fit into the big narratives people want to create or believe about the country. Unlike many elsewhere, especially in the west of Ukraine, most of its people did not yearn for generations to be part of a united and independent Ukrainian state but, as conflict engulfed parts of the east in 2014, they realized they did not want to die to be part of Russia either.

Bessarabia is isolated and often forgotten, but in many crucial ways its stories and those of its people are just the same as those in the rest of the country. After nearly a quarter of a century of independence almost everyone in Ukraine, unless they are very rich or a politician, or quite often both, feels angry and resentful at someone. This is the story of modern Ukraine, only in Bessarabia it is often more so. In that sense, understanding Bessarabia means understanding why you need a ticket to get here, and understanding that means understanding something about Ukraine.

To understand what “Ukraine” and “Ukrainian” mean, we need to understand how names are used in different ways in different contexts. Here the issue is: what is Bessarabia? Today the appendix curls out west of Odessa. From the rest of the country there are only two roads in. One crosses a rickety bridge over the Dniester, which also serves as a railway bridge. To the north of this is a vast liman or lagoon-cum-estuary where the river flows out to the Black Sea. At the top of the liman is the second road. Here you cross the bridge over the Dniester at the town of Mayaki and you get to the border point where they give you the ticket. To the west, Bessarabia is bounded by the Danube and to the north by Moldova.

Bessarabia has nothing to do with Arabs, as its name might lead one to conclude. Its name derives from that of the Basarabs, the medieval Moldovan princes who once held sway here. Historically, the region that is now Ukrainian, most of which also has the alternative name of Budjak, was the core of Bessarabia. Once the Russians took it from the Ottomans and consolidated their control with the Treaty of Bucharest in 1812, it became a part of what they called New Russia or Novorossiya. The Russians then used the name Bessarabia to describe both this southern part, what is now Moldova, and some lands to its north, which are also now in Ukraine. Today, says Anton Kisse, an ethnic Bulgarian politician and local big shot, it is hardly surprising that people are worried. After all, war and change come here every generation or two.

Ottoman mosque, now a museum, surrounded by weaponry from the Second World War. Izmail, December 2014.

In my notebook I started to write down the dates of who had ruled this land during the last two hundred years during an interview with Alexander Prigarin, an ethnographer and specialist on the region at Odessa University. After a few lines he became exasperated and took my book to write himself.

1812–1856 Russia

1856–1878 Moldova

1878–1918 Russia

1918–1940 Romania

1940–1941 USSR

1941–1944 Romania

1944– USSR

It seems odd that he ended his list like this and not like this:

1944–1991 USSR

1991– Ukraine

And perhaps not to complicate things, he left out:

1917–1918 Moldovan Democratic Republic

…which only lasted a few weeks.

And this is the simplified version! In detail it is an even more tangled web, as some districts remained Russian after 1856 and Moldova united with Wallachia in 1859 to form Romania. But the result of this history is the ticket. In 1939 Stalin and Hitler drew their infamous line from the Baltic to the Black Sea in the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. The Soviet Union had never recognized Romanian control over all of the old Russian province of Bessarabia after the First World War. So now, in the new circumstances, they explained in the wake of the pact that they were just reasserting control over what was rightfully theirs, a forerunner of what would happen in Crimea in 2014, although there Russia had previously recognized Ukraine’s territorial integrity. After the Soviets took control of this southern part, with its higher proportion of Slavs, it was amputated from the rest of the region and given to Ukraine and a sliver of territory to the east of the Dniester River given to the new Moldovan Soviet republic. But, as it was all in the Soviet Union, it did not really matter if the road from Odessa passed through Moldova and that Moldova itself, already stripped of the Bessarabian Black Sea coast, had no access to the sea even via the Danube. In 1999 the Moldovans and Ukrainians made a deal though. Ukraine got to control the road which runs through the village of Palanca, where women sell apples by the side of the road, and in exchange Ukraine gave Moldova a 430-meter strip of territory which adjusted the map and allowed the Moldovans to build themselves a port on the Danube at Giurgiulesti, which otherwise was cut off from the river by a virtual stone’s throw. From afar, all this seems like obscure detail—but to those who live with the vicissitudes of Soviet cartography, coping with the results is everyday life. These are small places, but Ukraine is now faced with a war based on maps and history. Why did much of the Russian-speaking east, south and Crimea end up Ukrainian, ask those who reject its sovereignty—not Russian?

Читать дальше