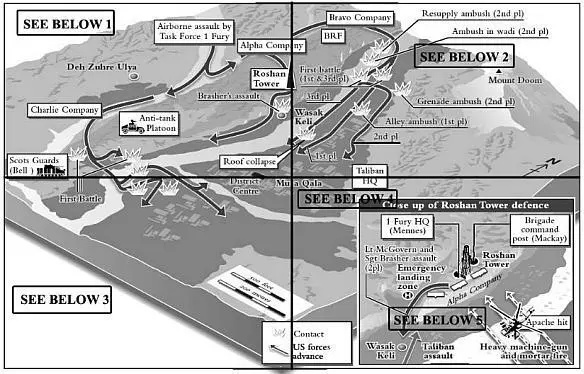

MUSA QALA WADI

7–11 DECEMBER 2007

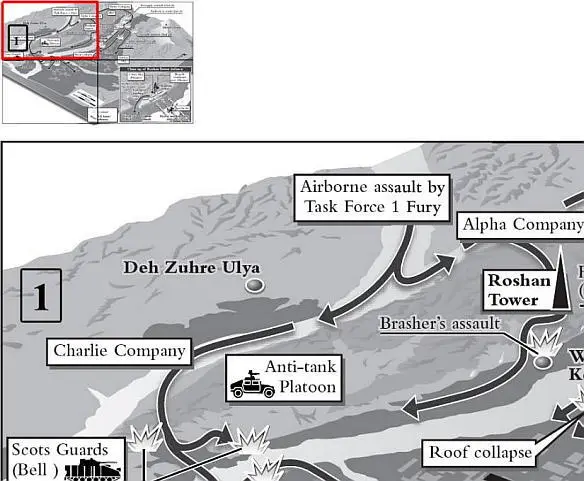

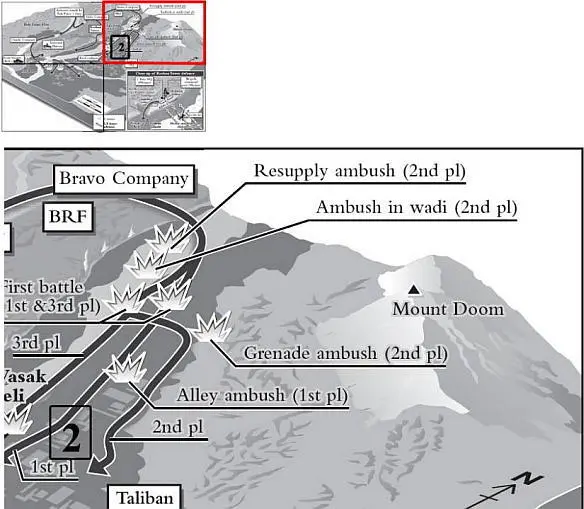

The heaviest fighting in the battle for Musa Qala is between Taliban forces and US paratroopers Task Force 1 Fury of the 82nd Airborne Division. After landing by helicopter at sunset on 7 December, 1 Fury’s three companies march through the night. All are in heavy contact with the Taliban at dawn.

24. Night of the Spectre: 9 December

East of Musa Qala, on Roshan Hill with Alpha Company, 1 Fury, 0700

Sunrise across the wadi ushered in a day that few in 1 Fury will ever forget.

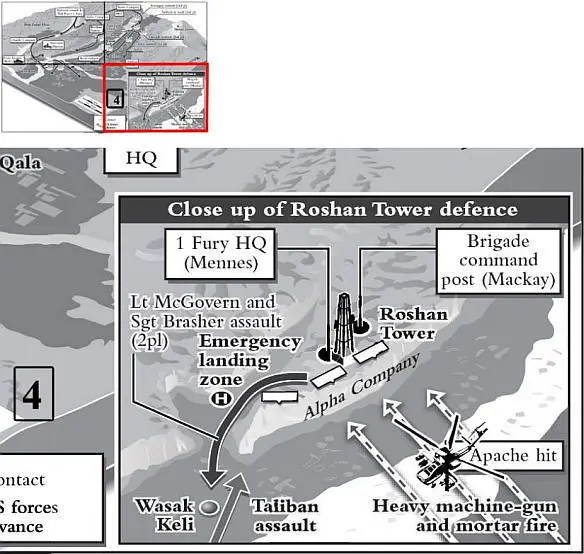

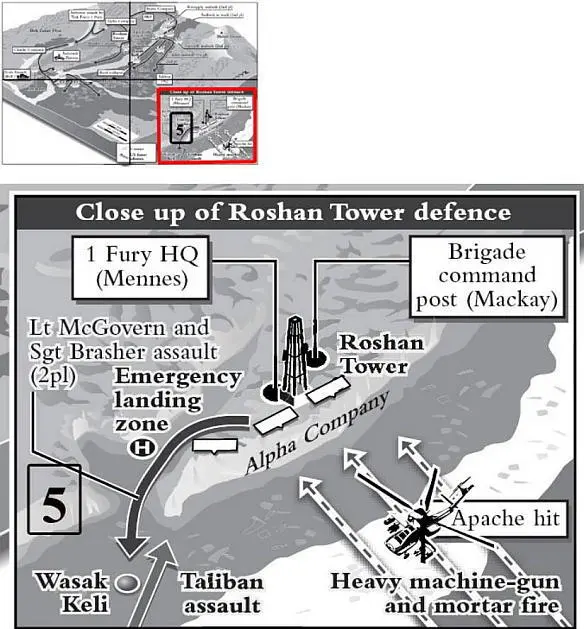

As the men blinked in the early morning light, the rounds from the Dushka guns started whizzing again over their trenches. Forward observers were ready to coordinate return fire. Suspected firing points were identified. The 81mm mortars were called in from the rear, so were the British 105mm artillery guns, firing from the desert. The scouts in their Humvees on the ridgeline thought they saw the Dushka moving on a truck. They called in a mortar strike. The Apaches now on station thought they saw four men crawling into a firing position. They engaged them with their 30mm cannon. And this was all in the first hour .

Then all eyes turned behind after a loud boom. A black-grey mushroom cloud billowed up. Radios crackled. The scout platoon had been trying to push up the back of Roshan Hill. A Humvee had struck a pressure-plate IED. Corporal Tanner O’Leary, twenty-three, from South Dakota, was killed outright. Another soldier was wounded.

There was no time for contemplation. Up on Roshan Hill the firing became more intense. The Taliban Dushkas were getting braver by the minute. Most times, in most contacts in Helmand, the arrival of Apache attack helicopters on station would bring a lull in the battle. The Taliban would hide. But in this battle it just intensified. The Taliban started to fire directly at the choppers.

Some thought the .50 calibre rounds being fired by the Taliban that day were explosive-tipped. They seemed to be blowing up as they made impact. However many guns the Taliban had, it seemed they could take a heavy pounding. The Apaches were firing back at their positions with 30mm rounds and Hellfires. They took out a truck full of weapons. They took out one, perhaps two Dushka positions. But if they flew away and then returned, then machine-gun fire would pour out from a whole new spot.

The desert west of Musa Qala, with B Company, 2 Yorks

The helicopter finally came that morning for Jonno’s body. Nichol Benzie, the Chinook pilot, remembered being woken up to go and do the mission. As with all flights in those days, it was not a case of simply going and getting Jonno and coming back. They also picked up some prisoners. And then they were ordered over to pick up both O’Leary’s body and the gunner who had been injured in the explosion. As they approached, recalled Benzie, they saw a Humvee that had been destroyed in a really, really bad way. ‘And you’re always nervous, then, landing because if a mine’s blown up the Humvee, then what other mines are there?’

Jonno’s departure on Benzie’s chopper meant B Company could finally move off the ridge. But first Jake wanted to get rid of Jonno’s Vector, as well as the Afghan truck. It was partly to destroy the sensitive equipment and to deny any ammunition left behind inside the twisted wreck to the enemy. But it was also about providing some closure for the lads. So everyone could move on.

Packing up camp, B Company moved off with the American Green Berets and the ANA along the desert plateau. They stopped about a mile away. The American forward air controller was going to call in an air strike: one JDAM on each of the vehicles.

On the ground it seemed a long, long wait – almost two hours of just standing waiting for the plane to drop its bombs. All the time the vapour trails in the sky showed there were plenty of aircraft on station who could do the job. What the soldiers on the ground did not see, however, was how this one request from Jake to deny two vehicles caused one of the biggest rows back at the Brigade HQ of the entire air operation.

It all came down to how air strikes were organized. When troops were in contact – their lives facing an immediate threat – then commanders on the ground like Jake had almost total authority to call in whatever close air support they needed. Every pilot had responsibility for what he dropped, and he would always ask for some double or triple checks. But there wasn’t the need for every target to be approved by someone at a higher level. But strikes that dropped bombs when no one’s life was in immediate danger were governed by a whole set of different rules. Time and again questions came back from higher command demanding: ‘Are there any civilians near by?’ and ‘Do you know where all the friendly forces are?’

On the ground, Jake was insisting there were neither ‘friendly forces’ nor civilians near by. Above him, the pilots were getting frustrated. All down the Musa Qala valley, and across Helmand too, there were troops in contact. But these planes were just circling around and burning up their fuel waiting for an OK to destroy two empty vehicles in the desert.

Simon Tatters, the brigade air liaison officer, could work out what was happening. A rogue Predator was wandering around near the scene and collecting pictures to which the brigade had no access. Controlled from Nevada but – apparently – under the control of an unknown commander, it was being used to second-guess the judgements that Jake and the forward air controller and the human pilots were making. The Predator, recalled Tatters, was ‘providing, from our point of view, disinformation’. The picture they were building up from the ground was being questioned, and the ‘frustration slowly built and built and built.

Among their augmented air team, the brigade had three American air force colonels, so Tatters was glad it was the American who was typing out the ‘fucks’ and ‘bullshits’ on the electronic chat as the frustration grew.

The first aircraft overhead, a pair of F-15s, went away and refuelled from a tanker aircraft, came back, waited around and returned to base without dropping a thing. Now a couple of A-10s were on call. And they too were getting angry. They had been pulled away ‘from the fight elsewhere’.

‘The aircraft had good eyes on,’ said Tatters, ‘but it was a time-sensitive target, because we needed to deny these vehicles to allow the ground units to move on. And it just went on and on and on and on, and meantime, there were a lot of things happening elsewhere. This was starting to detract.’

After two and a half hours, the permission finally came through. It came with relief but also derision. Tatters guessed the final word had come from the general in Qatar. Perhaps he was on holiday somewhere and they had needed to track him down.

Читать дальше