One particular unidentified Predator was in the way, obstructing a pair of fast jets trying to provide close air support to some troops in contact. After several failed attempts to coordinate this UAV with the close air support, Quaife ran out of patience – ‘What the fuck are you doing to me? You’re in my airspace, YOU’RE IN THE WAY’ – and the Predator pilot – in his control room back in Nevada – started getting stressed, telling Quaife to ‘Lose your attitude, dude.’ The row ended up with an email from a US Air Force 2 star, reminding everyone that Brigade had the ‘hammer’ – the control authority for the airspace around Musa Qala.

There was also a US air force general who sneaked into the scene without notice in his own personal fighter jet. Nearly crashing with a Predator and a pair of Harriers, he sent back an ugly message afterwards complaining about overcrowding. ‘Well, that’s exactly why you don’t arrive unannounced,’ thought Tatters.

The choppers took another turn.

Then finally, the argument on approving the air strikes had run its course. An approval message flashed down from the Combined Air Coordination Centre in Qatar. The on-station B1-B was clear to drop. But it was too late, there wasn’t enough time for him to drop his weapons before the helicopters would have either to land or head back. Time had run out.

Some artillery strikes still went in, but they hit only six out of the thirty-four the Americans had originally requested. From his helicopter, Colonel Richardson decided it was not enough. He radioed the choppers: ‘Switch to the Alternate LZ.’

All in all the delay had been little more than fifteen minutes. But the switch of landing zone was to change the whole battle. As the crow flies the new zone was less than 2 miles from the original site, but it was one whole valley further away from Musa Qala.

The Chinooks finally began their descent. The British pilots were happy to hear the landing zone had changed. The primary one was in a narrow wadi below a ridge with well-known enemy trenches. Bringing all the helicopters into that space at one time would have been no laughing matter.

The British packet came in second after the Americans – coming as fast as they could with their Black Hawk guides and then flaring in the last seconds in a gut-wrenching twist to cut their speed and bunch themselves up to land side-by-side in the dust and gravel. As the ramp went down, the pilots held their breath. The way they saw it the first packet would wake up the enemy. Enough time to lay on a full Afghan welcome for the Brits.

A stopwatch in the cockpits counted the seconds as the paratroopers unloaded. Paul Curnow just remembered sitting there raising his eyes to the top of the wadi and ‘waiting for something to happen, waiting for incoming’. But nothing came. It was all clear, and the ramps went up, and the choppers burst away. They turned south and low. It wasn’t quite over yet. They still had to get out of the wadi.

As they pulled themselves out and crested the ridge they finally realized: ‘We’re going to get through this, all the build-up and all the fear, it had ended up without a shot.’ Just then they saw a convoy of British vehicles strung out. It was the Brigade Reconais-sance Force on their way into action. In the light of the setting sun they saw a huge Union Jack flapping from an antenna and a soldier standing behind a .50 cal, giving them one incredible wave and shouting ‘Yeah!’

The only thing missing, thought Curnow, were the credits for the movie rolling down his screen.

Deh Zohr e Sofla, with B Company, 2 Yorks, 17.00

It was time to withdraw.

We walked slowly back up the dirt road. The body of the Taliban was left lying in the mud, covered in a cloth, as were the bodies of the lorry drivers. It was better that local people, when they felt it was safe, should come forward and give the men a decent burial.

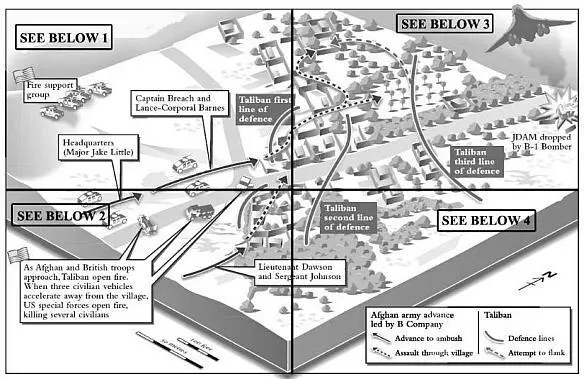

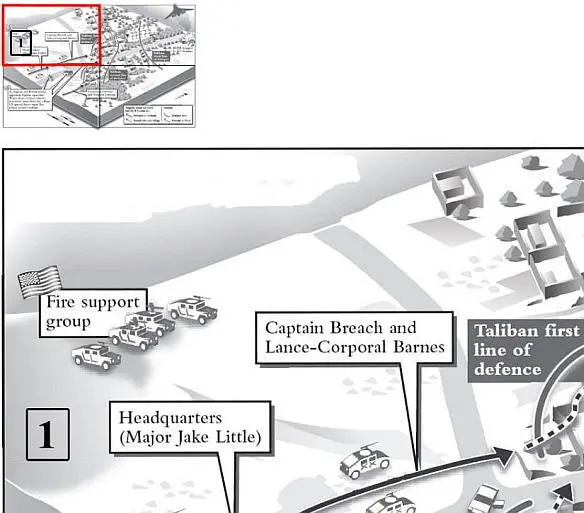

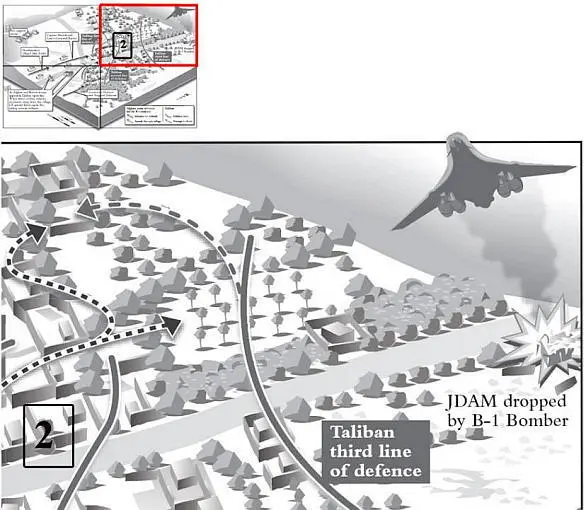

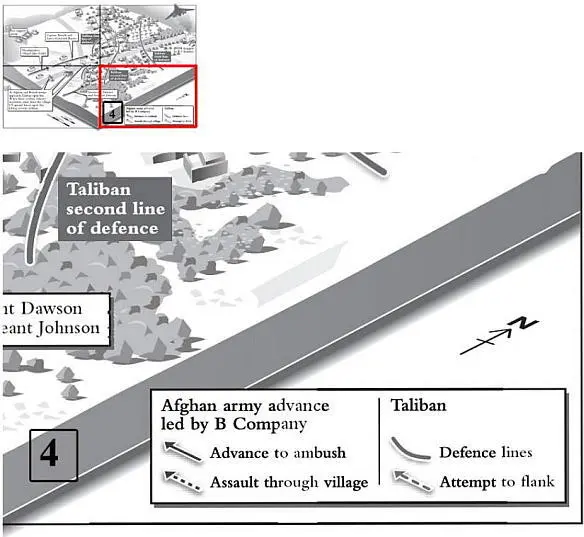

FEINT ATTACK ON VILLAGE OF DEH ZOHR E SOFLA

7 December 2007

23. Battle for the Wadi: 8 December

One mile south-west of Musa Qala, 05.33

An American paratrooper stood in pitch darkness. He was catching his breath after a long march. As he smoked, he shielded the orange glow of his cigarette in the cup of his hands. He looked upwards, and, as the tobacco burned down, the sky began to change. From the east came the dimmest of lights. One by one, the stars were snuffed out.

Then he heard in the wind the call to prayer. The words came not from some loudspeaker. They were shouted in Arabic, as they had been for fifteen centuries, by a lone man standing on the roof of a town mosque.

Allahu Akbar

Ashhadu an la ilaha illa Allah

Ashadu anna Muhammadan Rasool Allah

God is Great

I bear witness that there is no god but Allah

I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of Allah

Rise up for prayer

Rise up for Salvation

Prayer is better than sleep

Allah is Great

There is no god but Allah

One hundred yards from the American soldier and his platoon, a group of young Afghan men shook away their thin blankets. They leaned their weapons on the side of a mud-brick compound and prostrated themselves towards the holy city of Mecca. Few of these men doubted God’s will that today would be the day of shaheed , of holy martyrs.

The paratroopers of 1 Fury had been marching through most of the night, slowed down by their unexpected arrival at a more distant landing site. The absence of a moon did not help. The night-vision goggles they used were high-tech, but they worked by amplifying the ambient light. On utterly dark nights like this, with no illumination but the stars, they had all the clarity of a poorly tuned television set. It all made for hard going as, laden with supplies, the paratroopers had trudged on foot through a series of rocky desert ravines.

As they emerged from the desert, the stage for the battle ahead was to be an altogether different scenery: the cultivated green zone of the Musa Qala wadi. Overlooked by sharp cliffs, it stretched as wide as 3 miles by the town itself. But it was cut in two by a flat gravel riverbed which, as much as 600 yards across in places, was the town’s most natural defence. A small but fast-flowing and treacherous stream snaked through the middle, and the town of Musa Qala lay on the far, western bank.

Brian Mennes, the 1 Fury commander, proposed to defeat the Taliban in Musa Qala by sweeping towards it from three sides. His Bravo Company would cross the riverbed and come down from the north. Charlie Company would also cross and then sweep up from the south, and Alpha Company would seize the high and low ground opposite the town itself.

By first light on 8 December, the slow march had put them behind schedule. Bravo was across the riverbed but had established only a toehold, and Charlie, who had the furthest to walk, had yet to make it across. But Alpha had successfully taken the Roshan Tower, a mobile telephone mast on a twin-peaked hill that overlooked and dominated the town and where Mennes had now established his command post.

Читать дальше