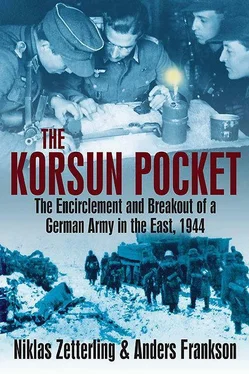

Niklas Zetterling and Anders Frankson

THE KORSUN POCKET

The Encirclement and Breakout of a German Army in the East, 1944

This book deals with a battle known by two names. In Soviet literature it is usually called the battle at Korsun, or even the Korsun-Shevchenkovskii operation, while the Germans prefer to call it the battle at Tscherkassy (Cherkassy), or the “Kesselschlacht bei Tscherkassy.” As the small town of Korsun for most of the time was located at the center of the pocket containing the two surrounded German corps, it seems somewhat more appropriate to call it the battle at Korsun, rather than Tscherkassy, which was situated outside the pocket and which was held by the Red Army before, during, and after the battle. Furthermore, as it was the Red Army that initiated the battle, it would seem reasonable to grant the Soviet side the favor of naming it. On the other hand, few people have a map that will show them where Korsun is located. Chances are far better that they will find Tscherkassy (or Cherkassy, depending on how it is translated) on their maps. We have opted to call it the battle at Korsun in the text and the title of this book is The Korsun Pocket.

Our interest in the battle at Korsun began about 20 years ago. What struck us was the unusual drama of the battle, and the fact that it was in many ways a more even battle than most Eastern Front clashes at this stage of the war. Overall the Red Army had the advantage of numerical superiority, as it had elsewhere on the Eastern Front, but by assembling a significant number of Panzer divisions, of which two were in quite good shape, the Germans managed to collect an attack force and make a determined effort to rescue the two corps that had been surrounded by the initial Soviet attack. Thus it is one of the relatively few battles in World War II where both sides were attackers as well as defenders. To this is added the foul weather, which played havoc with the plans of the generals, so that the stage was set for a dramatic battle, although its scope was not on a par with renowned confrontations like Moscow, Stalingrad, and Kursk.

Relatively little is written on the battle at Korsun. In English it is mentioned in several books, but rarely are more than a few pages devoted to it. In German there are more books written, including volumes focusing on the Korsun battle only. These include books written by men who took part in the battle, either as a high ranking commander, like Nikolaus von Vormann, or as a non-commissioned officer (NCO), like Anton Meiser. In Russian there is also some literature that describes the battle, but it does not present detailed description.

For the German side this does not pose a significant problem because the archival records of many of the units involved are available, either as microfilm at the U.S. National Archives in Washington, D.C. or in the form of the original papers at the Bundesarchiv in Freiburg, Germany. These documents have formed the basis of our description of the German forces and their actions. Other German sources have constituted a complement.

Information on the Soviet side is much more scarce. The most important source has been the Soviet General Staff Study, which was written in 1944, but it is a source with many problems. When comparing it to the German archival documents it is clear that most of the Soviet General Staff Study’s statements on the Germans are wrong. Many explanations found in the study are untenable. From what we have seen of Soviet archival documents on the battle it seems that the Study was partly written as propaganda, although it was not intended for public use. Despite these limitations, we decided to use it, but with great caution. Fortunately we also obtained access to some Soviet archival records, but these were not as extensive as those for the German side. As we have preferred to say too little, rather than to risk making erroneous statements, we have not been able to give such extensive coverage of the Soviet side as we have done for the German side. This is not due to any bias on our part, but rather reflects the availability of reliable sources. Indeed, we could have described the German activities in much more detail, but we had to prioritise the material in order to produce a reasonably balanced book. For the Soviet side, on the other hand, we have included as much as possible of what we found relevant and reasonably reliable. Despite these limitations it has been our intention to present as much new information as possible, with references to enable the deeply interested reader to look for further information about the battle.

The maps deserve some comments. We have used a variety of sources to produce them and the level of detail available in the sources differed considerably. Thus the information found in the maps is varied. In some cases we have opted to include information on the location of specific units, even though we do not have information on the location of all units involved. Finally it must be said that the frontlines were not always as clearly defined as they appear on the maps. In many situations the units were stretched over wide areas, with very little infantry to maintain a coherent defensive front. In such situations both sides often resorted to maintaining control over the villages and keeping an eye on the terrain in between. In such situations the frontlines indicated on the maps can at best be regarded as approximate.

We hope to have written a book that can be read by those who wish to discover something they have not read about before, as well as by those who have a deep interest in World War II and already possess an extensive knowledge about the conflict. Whether we have succeeded or not is up to the readers to judge. Our judgment is that the book has benefited considerably by the assistance of various other people: Karl-Heinz Frieser, Kamen Nevenkin, Mirko Bayerl, and especially Egor Sjtjekotichin, who helped us with Soviet archival documents.

Both armies allowed infantry to ride on armored vehicles, in this case a German StuG III assault gun. (SIPA PRESS)

In the afternoon on 8 February 1944, Colonel Hans Viebig, commander of the German 258th Infantry Regiment, picked up the phone and tried to contact some of his superior commanders. He had just received important information and it was necessary to immediately convey it. Within a short time Viebig had Johannes Sapauschke, the chief of staff of XXXXII Corps, at the other end of the connection. Sapauschke was told that a Soviet jeep, carrying a large white flag and accompanied by trumpet blasts, had approached the defense lines of the 258th Infantry. Obviously it was a parlayer, and Sapauschke was not surprised.

Together with the XI Corps, the XXXXII Corps had been surrounded for almost two weeks by Soviet troops. They had cut off the salient held by the two German corps and created a pocket near the Dnepr River, about 130 kilometers southeast of Kiev. By now, ammunition was running low for the surrounded Germans, who could not hold out much longer. Many soldiers who were ill or wounded had been assembled near the little town of Korsun, where doctors and nurses did their best to care for them, but shortages of medicine and other equipment made their struggles difficult. A few thousand wounded had been evacuated by air, but still there were more than 50,000 men inside the pocket created by the Soviet 1st and 2nd Ukrainian Fronts, commanded by generals Nikolai Vatutin and Ivan Konev.

Читать дальше