Sablin might scribble a few comments in the margins and make a suggestion or two, but what he does not want to see happen is officers merely standing in front of their sailors and reading the notes.

This is the heart and soul of Communism. The Soviet people not only depend on the sailors to defend the Motherland with their lives but also expect the sailors to understand what they are fighting for and believe in it.

The Rodina believes in you; she only asks, dear Comrades, that you believe in her.

Pure Communism, and with it prosperity is just around the corner. Each five-year plan sees huge progress on all fronts, in manufacturing, in agriculture, in the glorious strides that the scientists have made in space, and in the magnificent sacrifices that the men in uniform have made and continue to make.

The ideals of Marx and Lenin are just as much alive today as they have ever been. Capitalism is the religion of greed and of the self and will fall under its own weight.

Sablin wants to believe the Party line with all his heart and soul. But like just about everybody aboard the Storozhevoy, and every other warship in the fleet, he knows that this is just a bunch of bullshit. All the bigwigs across the Soviet Union meet once every five to seven years in Moscow to tell the nation that progress is being made. Ministers of agriculture, transportation, buildings, defense, and culture all come to the podium and tell outright lies about increased farm yields when food is scarce, about new roads when streets even in Moscow are so filled with potholes that most cars are driving around with missing hubcabs and broken shocks, about new apartment buildings, which are crumbling even as they are being built, about improved defense, which is draining the national treasury, leaving little or nothing for the people, and about culture, which is actually the one boast that is not entirely a lie. The Bolshoi Ballet Company continues to be the best in the world, and Soviet symphony orchestras are nothing less than stunning.

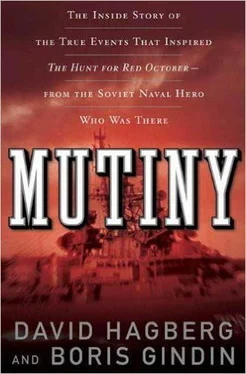

“They were traitors in the pure meaning of the word,” Gindin says. “All these ministers and the entire government were corrupt and totally dishonest with the people. They were enjoying the benefits of a luxurious life that we would never see or even dream of. They were telling us lies about the bright future while selling the people down the river.”

It’s the zampolit’s job to convince the officers of the truths of these lies and to make sure that the officers, in turn, convince the sailors. And until this early evening Sablin has done nothing short of a stellar job.

He’s standing in front of the officers waiting for them to make their choice, white or black, with him or against him. But this is mutiny, and the fact that he’s been such a terrific zampolit makes the situation all the more unbelievable. Maybe he is testing them.

Boris Gindin is only a couple of weeks from a much-needed leave to be with his mother and sister after his father’s death. Following Boris’s leave he would normally be reporting back to his ship for the next six-month rotation at sea. But that’s not supposed to be the way it’ll happen. Potulniy has agreed that if Boris sticks it out at the shipyard in Kaliningrad and gets the Storozhevoy in shape for his next rotation, the captain will write a letter of recommendation that will almost guarantee the shore job Boris wants.

Now this is an emotionally complicated situation for Gindin. On the one hand, he loves his job aboard ship, in charge of the gas turbine engines and other mechanical equipment. He has friends, he has a good crew who follow his orders without question, he has the respect of a man he considers to be one of the best captains in the Soviet navy, and despite his understanding of the propaganda coming out of Moscow, he is proud that he is making sacrifices protecting the Rodina. On the other hand, he is getting lonely and he’s getting tired of it. He wants to find a girl he can marry so he can settle down and raise a family. He doesn’t want to be like a lot of other young officers he knows, married and divorced already because six-month rotations at sea are almost impossibly hard on a new marriage. In his mind, he needs a shore job in order to find a wife.

In September Boris got a two-week assignment to the Zhdanov Shipbuilding Yard in Leningrad. Potulniy was ordered to send his gas turbine senior lieutenant to the yard because Gindin had been involved in the construction of the Storozhevoy and he had an intimate knowledge not only of the engines but also of how they should be installed in the first place.

Pushkin was Gindin’s hometown, but it was close enough to Leningrad that he had a propiska, which is a document giving a Soviet citizen permission to live somewhere. It’s often a major stumbling block to changing jobs. The employer might be willing, but unless the prospective employee has a propiska, taking the new job can be a moot point.

Shipyards building or repairing warships are required to have navy representatives to oversee the work, inspect the finished products, and sign off that the jobs have been done to specs. The gas turbine guy at the yard was gone, so Boris was sent to fill in.

From the day Boris arrived in Zhdanov he realized that this was a dream come true. It would be a perfect place for him to work and to continue with his career. Navy officers don’t have to serve aboard ship to get paid and to get promoted. There are important jobs ashore, such as that of a ship inspector.

Not only that, but Gindin figured that if he could land a job in Zhdanov, he would no longer have to spend six months at a stretch at sea, which meant he could find a girl, get married, and raise the family he wanted. He would be a naval officer, earning good money, getting the respect of the people around him, and yet almost every night he would be able to get aboard the train to Pushkin and go home.

It couldn’t get any better than that. The problem was how to do it.

Gindin scheduled an appointment with Captain First Rank Anatoli Goroxov, the man at the shipyard who was responsible for filling all the navy specialty positions—mechanics, electrical, acoustics, rocket systems, guns, and torpedoes. Gindin was filling in as a gas turbine specialist and he wanted to know whether the position was only temporarily vacant or Goroxov needed someone permanent.

As soon as Goroxov saw Gindin’s résumé and found out that he had a propiska for Leningrad and the area, the captain was over the moon. The Storozhevoy’s young gas turbine engineer was an answer to a prayer.

The only hitch was that since Goroxov had no real idea who or what Gindin was, he would need a reference. A letter from Captain Potulniy would do nicely.

Boris did his work at the yard without a hitch, and as soon as he reported back to the Storozhevoy he laid out his request to the captain. Potulniy was a good man. He didn’t want to lose Boris, whom he had come to trust and to rely upon, but by the same token he was a fair man who did not want to stand in the way of an officer’s advancement. So Potulniy said yes. He would write the letter of reference if Gindin would first go with the ship to the parade and celebration in Riga, then spend the two weeks at the Yantar Shipyard in Kaliningrad and finally help take the ship back to base at Baltiysk.

The main reason Potulniy laid those conditions on Gindin was because Captain Lieutenant Alexander Ivanov, who was commander of BCH-5, Gindin’s boss, would be on leave. The job then of running the entire mechanical, electrical, and steam boiler/fuel group would fall on Gindin’s shoulders.

Of course Gindin jumps at the captain’s kind offer. It’s a chance of a lifetime, a dream come true.

Читать дальше