Construction on the northern Coastal Battery No. 30, located near the Bel’bek River, proceeded much more slowly, and it was not until March 1928 that the Revolutionary Military Council allocated 3.8 million rubles to restart work, which did not actually begin for two more years. The project was badly organized, falling far behind schedule. Coastal Battery No. 30 was declared operational in mid-1934, but its complicated rangefinder system was not ready until 1940. However, the Achilles Heel of both 305mm batteries was that they drew their electrical power from Sevastopol’s power grid through a transformer station; if civilian power was lost the massive turrets would become inoperable. Auxiliary diesel generators were emplaced near the command-post bunkers, but only sufficed to provide power for communications and lighting. In fact, both 305mm batteries only became fully operational about six months before the German invasion. Lieutenant Georgy A. Aleksandr had arrived to take command of Coastal Battery No. 30 in November 1937 and Lieutenant Aleksei Y. Leshenko took command of Battery No. 35 in November 1940.

Once Stalin’s program of forced industrialization became established by the mid-1930s, the Black Sea Fleet was provided with greater resources, which enabled it to continue to improve its coastal defenses right up to the start of the German invasion. In addition to protecting Sevastopol, the Soviet Navy built three large coastal batteries to protect Kerch. The Black Sea Fleet also was provided with 300 antiaircraft guns to provide additional protection against enemy air attacks on its bases.

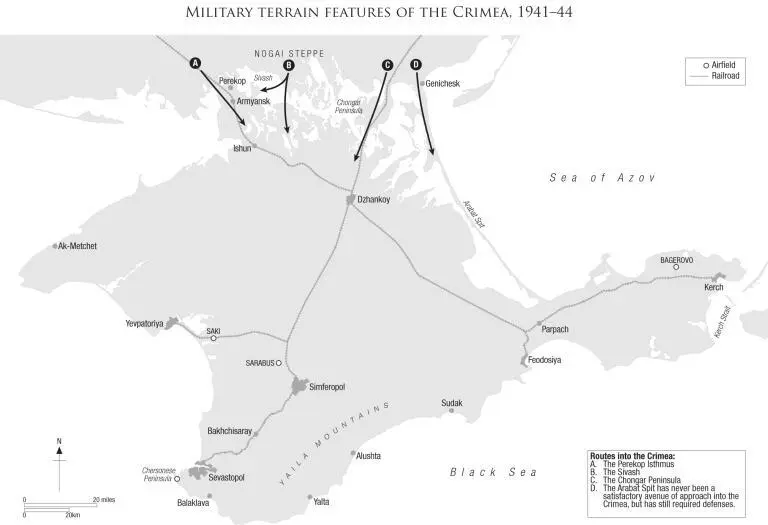

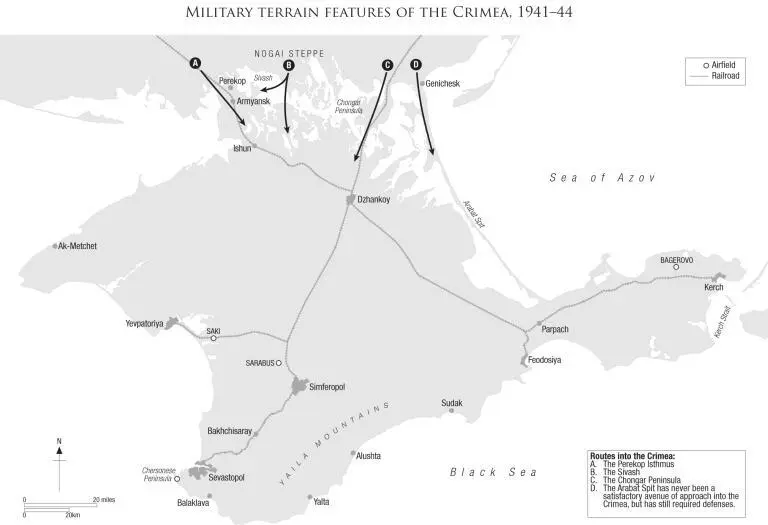

The Black Sea Fleet was responsible for the defense of its main naval base at Sevastopol, including coastal artillery and antiaircraft guns, while the Red Army was responsible for the land defense of the Crimea. There were no large naval infantry ( morskaya pekhota ) units formed in the Crimea at the start of the war. The only major Red Army formation in the Crimea in June 1941 was General-Lieutenant Pavel I. Batov’s 9th Rifle Corps, comprised of the 106th and 156th Rifle Divisions and 32nd Cavalry Division. This corps had been organized in the North Caucasus Military District and moved to the Crimea in mid-May 1941. Batov arrived at the corps headquarters in Simferopol just two days prior to the beginning of the German invasion. Falling under the authority of the Odessa Military District (to become the Southern Front on mobilization) Batov was instructed that his mission was to defend the Crimea against possible amphibious or airborne attacks, but he received no guidance on coordinating with the Black Sea Fleet. Altogether, Batov’s 9th Rifle Corps had about 35,000 troops and could be supplemented by local militia. The Soviet Air Force (VVS) units assigned to the Odessa Military District were grouped around Odessa and had no significant presence in the Crimea in June 1941.

The Soviet General Staff expected to fight future wars primarily on foreign soil, but acknowledged that enemy bombers and warships might be able to attack facilities in exposed areas such as the Crimea. Although Turkey was regarded as an unlikely threat, it had amassed more than 500 combat aircraft by 1940, making it the largest air force in the Balkans and the Middle East. Turkey’s acquisition of five foreign-built submarines also aroused Soviet concern. However, the ratification of the Montreux Convention in 1936 eased Soviet concerns by inhibiting foreign fleets from transiting through the Turkish Straits into the Black Sea.

The Kingdom of Romania had not been regarded as a potential enemy during the interwar period, but this changed when Germany and the Soviet Union signed their infamous Non-Aggression Pact in August 1939, which secretly condoned the Soviet acquisition of the Romanian border province of Bessarabia. In June 1940, the Red Army invaded Bessarabia and humiliated the Romanian Army, providing a motive for revenge. Five months later, a coup in Bucharest installed a fascist dictatorship, which quickly signed an alliance with Germany. The new German-Romanian alliance threatened the Soviet position in the Black Sea and for the first time since the Russian Civil War exposed the Crimea to possible enemy air or amphibious attacks. The Royal Romanian Air Force was rapidly developing its offensive capabilities in 1937–40 by taking delivery of Italian-made S79 medium bombers in 1938 and German-made He-111H medium bombers in 1940. By June 1941 the Romanians had formed four bomber groups with 96 bombers. In addition, they had three long-range reconnaissance squadrons equipped with 37 Bristol Blenheims – which posed a credible threat to the Black Sea Fleet.

Although the Soviet High Command was very concerned about the possibility of enemy amphibious landings in the Crimea, there was actually little possibility of that occurring. The Royal Romanian Navy was little more than a coast guard, with only four destroyers, one submarine, a single minelayer, and a few assorted auxiliaries. Romanian vessels were mostly obsolete and too outclassed to risk a head-on action against even part of the Black Sea Fleet. Furthermore, Romania’s merchant marine was tiny, with only 35 vessels of 111,678 GRT (gross register tonnage). Five of these merchantmen were modern vessels that would be useful for convoy operations, but the fact is that Romania lacked the ability to move more than limited quantities of troops and supplies across the Black Sea and had no ability to conduct an opposed landing.

CHAPTER 2

The Onset of War, June–August 1941

“The beauties of the Crimea, which we shall make accessible by means of an Autobahn. For us Germans, that will be our Riviera.”

Adolf Hitler, July 5, 1941

The exact details of Soviet strategic planning prior to Operation Barbarossa are difficult to quantify, but a number of Stalin’s pre-war strategic assumptions are clear. Foremost, Stalin believed that the Red Army was strong enough to deter a German invasion for the time being. Even if the Germans were tempted to commit aggression against the Soviet Union, Stalin believed that there would be adequate early warning to provide the Red Army time to prepare and deploy its forces for combat. Soviet military leaders were not ignorant of the threat posed by Germany after the sudden fall of France in 1940, but believed that their forces and plans would prevail. A series of war games conducted by the Soviet General Staff in Moscow in December 1940 suggested that the Germans would make their main effort in Ukraine, but that their forces would be pushed back to the border long before they reached the Dnepr River. [1] Richard W. Harrison, The Russian Way of War: Operational Art, 1904–1940 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2001), pp. 247–269.

When war came, the mission of the Black Sea Fleet was to assist the Red Army’s Southern Front in defending the coastline of the Black Sea. To that end, one of the primary tasks was laying defensive minefields outside Sevastopol and the other Black Sea ports. However, the fleet also wanted to use its naval air arm and submarines to attack enemy naval targets and facilities in the Black Sea – but little real planning had been put into this concept. At the start of the war in June 1941, the Soviet Stavka (high command) was wary that Turkey might allow Axis air and naval forces to move through her waters in defiance of the Montreux Convention, so Batov’s 9th Rifle Corps was ordered to deploy its forces along the coast from Yevpatoriya to Kerch to repel potential amphibious or airborne attacks. No effort was made to construct ground defenses at either Perekop or Sevastopol, since the Stavka believed that the fighting would be confined to the border regions. Instead, the Soviets would use the Crimea as a springboard for air and naval attacks on Romania in order to distract German forces from the main area of battle.

Читать дальше