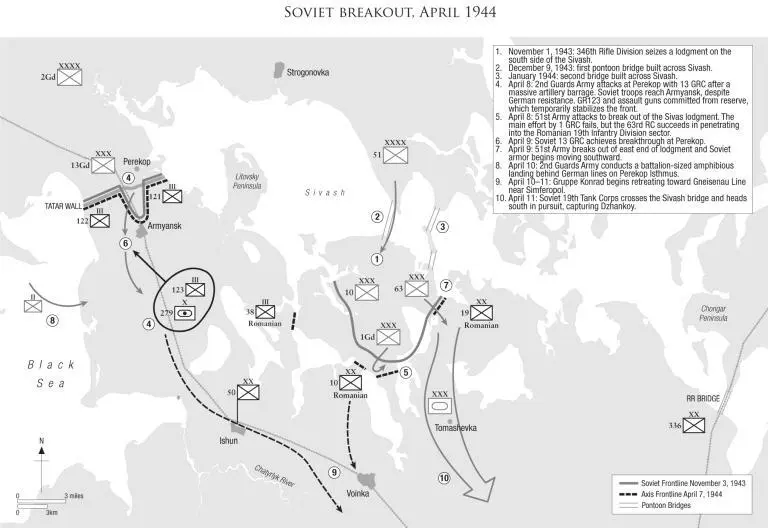

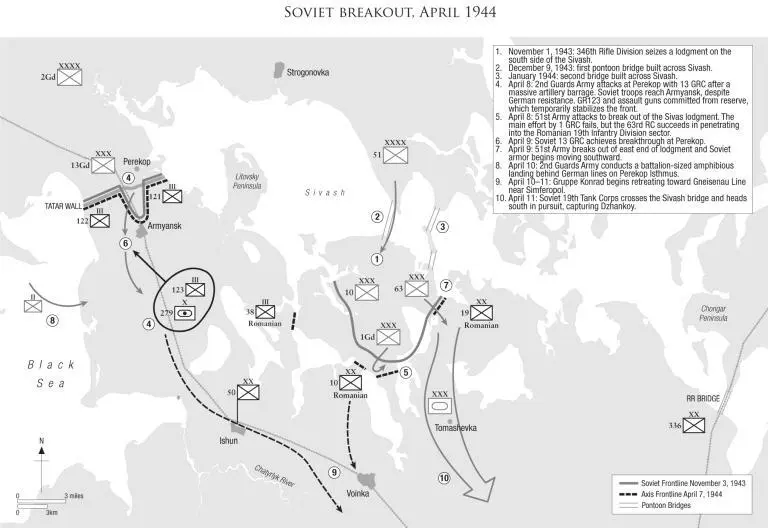

The next morning, April 8, 1944, the artillery of both the 2nd Guards Army and the 51st Army opened fire at 0800hrs. The Soviet artillery delivered a punishing 2½-hour-long prep fire against the Axis positions, from tube and rocket artillery, as well as heavy mortars. The 8th Army also returned again in strength, strafing and bombing the German positions. This time, II./JG 52 was able to intercept some of the Soviet bombers, although it made little difference. Soviet aircraft were everywhere over the Crimea. At 1030hrs, both Soviet armies commenced their ground attacks.

The 51st Army put its main effort against the center of the Axis perimeter around their Sivash lodgment, with the 91st Rifle Division and 32nd Guards Tank Brigade (32 GTB) attacking the Romanian 10th Infantry Division. The Romanian positions were well protected by mines and artillery, which broke up the Soviet attack. German StuG IIIs supporting the Romanian defense knocked out 27 of the 32nd Guards Tank Brigade’s 53 tanks. Surprisingly, a supporting attack made by Koshevoi’s 63rd Rifle Corps’ 267th Rifle Division and the 22nd Guards Tank Regiment against the Romanian 19th Infantry Division on the eastern end of the lodgment was more successful. Upon Tolbukhin’s specific recommendation, Koshevoi sent the 2nd Battalion/848th Rifle Battalion to wade across the shallow Lake Aygulskoe to outflank the Romanian positions. Although German sources claim that the Romanian 94th Infantry Regiment panicked and ran, Koshevoi notes that the enemy fell back slowly to a second line of defense and that only 550 prisoners were taken. [3] Peter K. Koshevoi, V gody voennye [ During the War ] (Moscow: Military Publishing, 1978).

When Kreizer realized that he was achieving no success in the center but that the Romanian 19th Division was buckling, he shifted the depleted 32 GTB and more infantry to reinforce this sector.

At the Perekop Isthmus, Zakharov’s 2nd Guards Army used relatively novel tactics. Instead of relying upon mass, as in previous offensives, Zakharov used only General-Major Porfiri G. Chanchibadze’s 13th Guards Rifle Corps in the initial attack. Like Stalin, Chanchibadze was a Georgian and he had a similar tough outlook, which made him well suited for a breakthrough operation. While the 126th Rifle Division and the 87th Guards Rifle Division launched supporting attacks on the flanks, the heavily reinforced 3rd Guards Division (3 GRD), under General-Major Kantemir A. Tsalikov, made the main effort in the center. Rather than just futilely throwing tank brigades at the enemy front, as in the past, Zakharov kept Vasil’ev’s 19th Tank Corps in reserve. The Soviet ground assault was preceded by artillery-delivered smoke rounds to reduce the accuracy of German automatic weapons, then the infantry rose up from the trenches and assaulted the enemy frontline trenches around Armyansk. [4] Konstantin V. Sychev (ed.), Boyeviye dyeystviya stryelkovoy divizii [ The Fighting Infantry Division ] (Moscow: Military Publishing, 1958).

Another Soviet innovation was the use of the 512th Separate Tank Battalion equipped with 16 TO-34 flamethrower tanks and the 1452nd Self-Propelled Artillery Regiment with a mix of KV-85 tanks, JSU-152 howitzers, and Su-76 assault guns to support the infantry attacks. The 3 GRD concentrated all its effort against a single German battalion, II./Grenadier-Regiment 122. This time, German mortars and automatic weapons failed to stop the Soviet infantrymen from reaching the first line of trenches, which were quickly taken in a frenetic moment of hurled grenades and submachine-gun bursts. Soviet flamethrower tanks burned out German machine-gun nests and antitank guns in the rubble of Armyansk, which was quickly overrun. Indeed, the Soviet breakthrough was going better than expected until the supporting armor ran into a very large field of antitank mines located behind the German HKL, which knocked out eight tanks. As the Soviet attack bogged down in the minefield, Panzerjägers engaged the stalled tanks, knocking out five more. German artillery was also directed onto the Soviet penetration corridor, destroying two JSU-152s with direct hits. Yet despite these losses, the 13th Guards Rifle Corps had torn a large hole in the German front line that could not be repaired, and Zakharov fed more troops into the breach. Sixt scraped some infantry platoons together to counterattack the flanks of the Soviet breakthrough and committed Hauptmann Karl-Otto Leukefeld’s I./Grenadier-Regiment 123 from reserve, but could not regain any ground. Konrad then sent the two batteries of assault guns forward and they were able to stem the Soviet advance, but lost a number of their vehicles. By the end of the first day of the ground offensive, Tolbukhin’s two armies had achieved local penetrations, but had not yet achieved a true breakthrough. Nevertheless, Gruppe Konrad had very little in the way of reserves left to influence the battle.

The next morning, both of Tolbukhin’s armies continued to pound away at Gruppe Konrad. Even after the loss of Armyansk, the 50. Infanterie-Division still had a front line of sorts across the Perekop Isthmus, but it was crumbling on the western side. Zakharov simply kept attacking with infantry and artillery until the German line finally broke around 1600hrs. With the help of massed Sturmovik attacks and a brigade of BM-31 multiple rocket launchers, Koshevoi’s reinforced 63rd Rifle Corps overwhelmed the Romanian 19th Infantry Division as well, and by late afternoon a small group of tanks were heading south. [5] Grylev, Dnipro-Karpaty-Krym: Osvobozhdenie pravoberezhnoi ukrainy i kryma v 1944 gody [ Dnepr-Carpathians-Crimea: The Liberation of the Right Bank of Ukraine and Crimea, 1944 ].

Konrad alerted Jaenecke that his forces could only delay the enemy and that he should activate plan Adler as soon as possible. After several hours of hesitation, Jaenecke activated Adler at 1900hrs on April 9 – without informing the OKH – and ordered Allmendinger’s V Armeekorps to abandon its positions at Kerch and retreat immediately toward Sevastopol. Eremenko was quick to note the German preparations to retreat, which included destruction of the harbor facilities in Kerch, and immediately ordered his ground forces to advance and the 4th Air Army to attack German convoys heading westward. Tolbukhin also spotted preparations by Gruppe Konrad to withdraw to its second line of defenses at Ishun and ordered Vasil’ev’s 19th Tank Corps to cross the bridge across the Sivash and enter the battle through the 51st Army’s breakthrough zone. Although the crossing was slow, it caught the Germans completely by surprise.

While Gruppe Konrad was struggling to maintain its positions on the Perekop Isthmus, Zakharov decided to increase the pressure on the German defense by conducting an amphibious landing behind the German lines on the Black Sea. Before dawn on April 10, 512 troops from Captain Filipp D. Dibrov’s 2nd Battalion/1271st Rifle Regiment were landed on the coast. As usual, the troops landed without heavy weapons and could hold only a small beachhead. Gruppe Konrad soon counterattacked with a company of infantry and several assault guns, but the Germans could not spare sufficient troops to eliminate the beachhead. Consequently, Dibrov’s battalion was the final straw that convinced Konrad to abandon his remaining positions on the Perekop Isthmus and retreat to the second line of defense at Ishun. This retreat proved difficult, since some sub-units of Sixt’s 50. Infanterie-Division were already bypassed and a number of artillery pieces and flak guns had to be abandoned. Indeed, Gruppe Konrad put up only token resistance at Ishun for a few hours, since the breakout of the 51st Army from the Sivash lodgment threatened to cut them off. Konrad, whose headquarters was in Dzhankoy, directed his forces to pull back to the Gneisenau Line.

Читать дальше