Paul Brickhill

THE DAM BUSTERS

To the men living and dead who did these things

CHAPTER I

A WEAPON IS CONCEIVED—

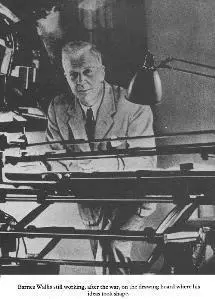

THE day before the war started Barnes Wallis drove for five hours back to Vickers’ works at Weybridge, leaving his wife and family in the quiet Dorset bay where they had pitched tents for a holiday. He had that morning reluctantly decided that war was not only inevitable but imminent, and he was going to be needed at his drawing-board.

Wallis did not look like a man who was going to have much influence on the war. At 53 his face was unlined and composed, the skin smooth and pink and the eyes behind the hornrimmed glasses mild and grey; crisp white hair like a woolly cap enhanced the effect of benevolence. Many people who stood in his way in the next three years were deceived by this.

He spent the last night of peace alone in his house near Effingham, and in the morning, like most people, listened to the oddly inspiring speech of Chamberlain’s. Afterwards he sat in silence and misery.

One thought had been haunting him since the previous morning’s decision: what could he, as an aircraft designer and engineer, do to shorten the war? The thought stayed with him for a long time and through remarkable events before it was honourably discharged.

He had been designing for Vickers since before the first world war. In the twenties he designed the R.ioo, the most successful British dirigible. In the thirties he invented the geodetic form of aircraft construction and, using this, designed the Wellesley which captured the world’s non-stop distance record, and the Wellington, which was the mainstay of Bomber Command for the first three years of the war.

Vickers’ works, nestled in the baked perimeter of the old Brooklands motor-racing track, was turning out Wellingtons as fast as it could, and Wallis was designing its proposed successor, the Warwick. At this time he was on the design of the Warwick’s tailplane, which was being troublesome. Clearly any additional work would have to be done in his own spare time and there was, also quite clearly, not going to be much spare time.

Bombers and bombs were the directions in which he was most qualified to help. Bombs, particularly, seemed a fruitful field. He knew something about R.A.F. bombs, their size, shape, weight and so on; the knowledge had been essential when he was designing the Wellington, so that it could carry the required bombs over the required distance. It was not knowledge which, in Wallis, inspired complacency. The heaviest bomb was only 500 Ib., and aiming was so unpredictable that the Air Force was forced to indulge in stick bombing—you dropped them one after another in the pious hope that one would hit the target. One hoped then that it would go off. Too many didn’t.

R.A.F. bombs, too, were old, very old. Nearly all were stocks hoarded from 1919. There had been an attempt in 1921 to design a better bomb, and in 1938 they actually started to produce them, but in 1940 there were still very few of them. Both new bombs and old were filled with a mediocre explosive called amatol (and only 25 per cent of the weight consisted of explosive). There was a far better explosive called RDX, but production of that had been stopped in 1937. (It was not till 1942 that the R.A.F. was able to use RDX-filled bombs.) Meantime Luftwaffe bombs contained a much more powerful explosive than amatol—and half the weight of the German bomb was explosive.

Wallis knew there had been an attempt in 1926 to make 1,000-lb. bombs for the R.A.F. but they never even got to the testing stage. The Treasury was against them; the Air Staff thought they would never need a bomb larger than 500 Ib., and anyway Air Force planes were designed to carry 500-pounders. Not till 1939 (did the Air Staff begin to think seriously again of the 1,000-pounder, and six months after the war started they placed an order for some.

These shortcomings were not so obvious then, particularly as all air forces favoured small bombs designed to attack surface targets. The blast of bigger bombs was curiously local against buildings, and a lot of little bombs seemed better than an equal weight of larger ones. Even larger bombs needed a direct hit to cause much damage and there was more chance of a direct hit with a lot of little bombs.

To Wallis’s methodically logical mind there was a serious flaw to all this. Factories and transport could be dispersed; in fact were dispersed all over Germany. Bombing (vintage 1939) would not damage enough factories to make much difference.

He started wondering where and how bombing could hurt Germany most. If one could not hit the dispersed war effort perhaps there were key points. Perhaps the sources of the effort. And here the probing mind was fastening on a new principle.

The sources of Germany’s effort, in war or peace, lay in power. Not political power, but physical power! Great sources of energy too massive to move or hide— coal mines, oil dumps and wells, and “white coal”— hydro-electric power from dams. Without them there could be no production and no transport. No weapons. No war.

But they were too massive to dent by existing bombs. One might as well kick them with a dancing pump! The next step— in theory anyway— was easy. Bigger bombs. Much bigger!

But that meant bigger aircraft; much bigger than existing ones. All right then— bigger aircraft too.

That was the start of it. It sounds simple but it was against the tenets of the experts of every air force in the world.

Wallis started calculating and found the blast of bigger bombs was puny against steadfast targets like coal mines, buried oil and dams. Particularly dams, ramparts of ferroconcrete anchored in the earth.

Then perhaps a new type of bomb. But there Wallis did not know enough about bombs and the logic stopped short.

The war was a few weeks old when the dogged scientist dived into engineering and scientific libraries and at lunch-times, when he pushed the problem of the Warwick’s tail-plane aside for an hour or so, he sent out for sandwiches, stayed at his desk and started to learn about bombs. At night at home he did the same, absorbed and lost to his family for hours. As the hard winter of 1939 arrived he progressed to the study of the sources of power.

Coal mines! Impossible to collapse the galleries and tunnels hundreds of feet underground. Possible, he decided, that a heavy bomb might collapse the winding shaft so that the lift would not work. No lift. No work. No coal. But that could soon be repaired.

Читать дальше