This decision reflected neither simplemindedness nor moral blindness. The Reichswehr understood, better than any army in the world, that total war and industrial war had generated new styles of combat and new methods of leadership. The officer no longer stood above his unit but functioned as an integral part of it. The patriarchal/hegemonic approach of the “old” Prussian/German army, parenting youthful conscripts and initiating them into adult society, was giving way to a collegial/affective pattern, emphasizing cooperation and consensus in mission performance. “Mass man” must give way to “extraordinary man”—the combination of fighter and technician who understood combat as both a skilled craft and an inner experience.

The soldiers were confident that once Germany’s young men changed their brown shirts and Hitler Youth uniforms for army field gray, their socialization away from National Socialism would be relatively easy. The army knew well how to cultivate them from its own resources. The new Wehrmacht had new facilities. Leave policies were generous. Food was well cooked and ample. Uniforms looked smart and actually fit—no small matters to young men on pass seeking to make quick impressions.

The conscripts were motivated, alert, and physically fit. Thanks to the eighteen months of compulsory labor service required of all seventeen-year-olds since 1935, they required a minimum of socializing into barracks life and were more than casually acquainted with the elements of close-order drill. Officers and noncommissioned officers were expected to bond with their men, leading by example on a daily basis.

The army was still the army, and NCOs had lost none of their historic set of tools, official and unofficial, to “motivate” recalcitrants and make them examples for the rest. But military service had for over a century been a major rite of passage for males in Prussia/Germany. The army’s demands had generally been understood as not beyond the capacities of an ordinarily fit, well-adjusted young man. That military service had been restricted during the Weimar years gave it a certain forbidden appeal. And a near standard response of older generations across the republic’s social and political spectrum to anything smacking of late-adolescent malaise or rebellion was that what the little punks needed was some shaping up in uniform.

Recruit processing differed significantly from both pre-1914 practice and the patterns in contemporary conscript armies. While not ignoring experience, aptitude, education, and even social class, the German sorting and screening system paid close attention to what later generations would call “personality profiles.” Determination, presence of mind, and situational awareness were the qualities most valued. Initial training in all branches can best be compared to a combination of the U.S. Army’s basic training with its advanced infantry training, informed by the Marine Corps’s mantra of “every man a rifleman.” That reflected the belief that infantry warfare’s moral and physical demands were the greatest. A soldier who could not meet them was less than an effective soldier no matter his level of technical proficiency. Misunderstandings and mistakes in combat were to be expected. Overcoming them depended more on character than intellect. And character in the context of combat meant, above all, will.

The question of nature versus nurture did not significantly engage the Wehrmacht. Long before Leni Riefenstahl celebrated Hitler’s version of the concept, the armed forces acted on the principle that a soldier’s will was essentially a product of cultivation. Drill was the means to develop the reflexive coordination of mind and body. Troops trained day or night, at immediate notice, in all weather, under conditions including no rations. Combat conditions were simulated through the extensive use of live ammunition. Casualties were necessary reminders of the dangers of carelessness and stupidity.

A persistent mythology continues to depict the German army of World War II as a “clean shield” force, fighting first successfully and then heroically against heavy odds, simultaneously doing its best to avoid “contamination” by National Socialism—a “band of brothers” united by an unbreakable comradeship. That concept of comradeship is arguably the strongest emotional taproot of what John Mearsheimer has memorably dubbed “Wehrmacht penis envy.” Soldiers and scholars inside and outside Germany have consistently cited “comradeship” to explain the “fighting power” the Reich’s opponents found so impressive.

Particularly in the context of the Russian front, the concept of comradeship has been described as an increasingly artificial construction, based on Nazi ideology, generated by material demodernization and consistent high casualty rates that destroyed “primary groups” that depended on long-standing relationships. Small relational groups based on affinity, proximity, and experience were above all survival mechanisms. A man physically or emotionally alone in Russia was a casualty waiting to happen. The ad hoc, constantly renewed and reconstructed communities resulting from heavy losses were held together by the old hands—sometimes of no more than a few days’ standing—who set the tone and sustained by the newcomers not only seeking but needing to belong in order to survive physically and mentally.

“Good” was in fact frequently defined as any behavior that strengthened the fragile, fungible, ad hoc community against external or internal challenges. But however deep ran their brutalization, the ground forces, army and Waffen SS alike, never degenerated collectively into what Martin van Creveld called “the wild horde.” Lawless and disorganized, committed to destruction for destruction’s sake, self-referencing to the point of solipsism, the horde can neither give nor inspire the trust necessary for the kind of fighting power the Germans demonstrated to the end.

Comradeship helped them to remain soldiers, not warriors or killers. And after 1945, for German veterans comradeship became the war’s central justifying experience. Few were willing to admit they had fought for Hitler and his Reich. The concept of defending home and loved ones was balanced, and increasingly overbalanced, by overwhelming evidence that the war had been Germany’s war from start to finish. What remained were half-processed memories nurtured over an evening glass of beer or at the occasional regimental reunion—memories of mutual caring, emotional commitment, and sacrifice for others. Traditionally considered to be feminine virtues, these human aspects of comradeship made it possible to come to terms morally and emotionally with war’s inhuman face—and to come to terms with the nature of the regime one’s sacrifices had sustained.

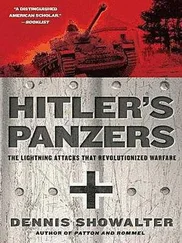

If the Soviets saw war as a science, the Germans interpreted it as an art. Though requiring basic craft skills, war defied reduction to rules and principles. Its mastery demanded study and reflection but depended ultimately on two virtually untranslatable concepts: Fingerspitzengefühl and Tuchfühlung . The closest English equivalent is the more sterile phrase situational awareness . The German concept incorporated as well the sense of panache: the difference, in horsemen’s language, between a hunter and a hack—or, in contemporary terms, the difference between a family sedan and a muscle car. It emphasized speed and daring, maneuvering to strike as hard a blow as possible from a direction as unexpected as possible.

The mobile way of war was epitomized in the panzer divisions. From its inception, the division was conceptualized as a balanced combined-arms force. Tanks and motorized infantry, motorcyclists and armored cars, artillery, engineers, and signals would train and fight together at a pace set by the armor. The panzer division would break into an enemy position, break through, and break out with its own resources, thereby solving the fundamental German problem of World War I. But the panzer division could also create opportunities on an enemy flank or in his rear areas. It could conduct pursuit and turn pursuit into exploitation. It could discover opportunities with its reconnaissance elements, capture objectives with its tanks, hold them with its infantry, then regroup and repeat the performance a hundred miles away.

Читать дальше