Hitler also came out in support of Scandinavian neutrality, particularly for Finland, and postwar research has shown that he did not in fact have any territorial ambitions in that region. All he desired was for the Baltic to remain open for German shipping and for the Swedish iron ore to flow into the Ruhr factories without interruption. But as Stalin saw things, there was something decidedly suspicious about the way the Germans were making such a fuss over Finland’s new regional orientation. Was Finland secretly acting as a broker between Germany and the Scandinavian states? Stalin’s suspicions were aggravated by the fact that the extreme right wing in Finnish politics was soon advocating just such a duplicitous policy; theirs was all a lot of hollow imitation-fascist rhetoric, and responsible Finns dismissed it as such, but the Soviet intelligence service did not write it up that way in their reports to the Kremlin.

The Russians consistently overestimated the influence of both extremes of Finnish domestic politics. When the Great Depression finally reached Finland, its effects spawned a fascist party called the Lapuan Movement (named after a town where a mob of conservative farmers had beaten up a rally of the League of Communist Youth in late 1929), led by a rather pathetic Mussolini clone named Kosola. Most of the Lapuans’ activity was mere hooliganism—taking leftists for a ride to the Russian border and bodily chucking them over the fence, smashing their mimeograph machines, and the like—but they captured sensational headlines in 1931 and 1932 with a kidnapping and an attempted putsch .

The kidnapping was the work of some right-wing thugs led by an ex-White general named Kurt Wallenius, and its victim was the elderly and widely loved first president of Finland, a Wilsonian law professor named K. J. Stahlberg. Threats of execution were issued when the Lapuans’ demands were not met, but in the end the whole thing degenerated into a nasty little farce: Wallenius and his henchmen were too incompetent to handle the kidnapping without bungling it and too irresolute to carry out their murder threat. The Finnish public was shamed and horrified by this pointless act of lawlessness, and a general backlash against the Lapuans greatly eroded their already dwindling popular support.

A tide of rumors ushered in the year 1932, the darkest of them concerning a planned coup d’état that Wallenius was anxious to mount before the Lapuans lost all their followers. The charismatic little scoundrel had been scandalously acquitted of his role in the Stahlberg kidnapping and was now in league with a clique of fascist officers in the Civic Guard, Finland’s territorial militia, totaling some 100,000 men, that traced an unbroken line of descent back to the White Guard of 1918. Finland’s various Communist parties had been outlawed in late 1931, so there was no longer any highly visible leftist threat for the right wing to focus its energies on; the new Lapuan objective was nothing less than the overthrow of the duly elected constitutional government.

The uprising fared no better than had the presidential kidnapping. A core of Lapuan fanatics jumped the gun and caught Wallenius’s gang of conspirators off balance. Wallenius’s group hurriedly tried to mobilize its forces and succeeded in putting into motion about 6,000 armed but hopelessly confused men. An impassioned radio speech by newly elected Finnish president Svinhufvud, an authentic hero of the civil war, took the backbone out of the uprising and left the hapless Wallenius in command of no more than 300 die-hard fanatics. The rebellion expired without a shot being fired.

By the end of 1932, Finland’s brief flirtation with fascism was all but over. The nation’s economy had improved, and the Lapuans, largely by virtue of their brutish tactics and staggering incompetence, had managed to alienate the propertied class from which they had previously drawn both financial support and a degree of borrowed respectability. The movement fragmented into a welter of impotent crank groups, such as the minuscule Military Force party, led by a man who openly worshiped Hitler, or the dreamy-eyed Academic Karelian Society, an association of fanatical irredentists who printed maps of something called “Greater Finland,” which included all of Estonia and stretched eastward as far as the Ural Mountains. One can easily imagine the impact such documents had when they fell, as several specimens did, into the hands of Stalin’s intelligence operatives.

Stalin was unrealistically influenced by the headline-grabbing antics of the Lapuans, the grotesque fantasies of the Karelian irredentists, and the exaggerated reports of agents who were eager to tell the Kremlin what they thought the Kremlin wanted to hear. From remarks made during his later negotiations with the Finns, it seems clear that Stalin really did believe that the interior of Finland seethed with class antagonism and fascist plotters and that all of Finnish society was undercut by smouldering grudges left over from the civil war days. Ill feeling persisted, of course—the conflict had been too bloody for all the scars to have healed in just two decades—but Moscow’s estimate of its extent, importance, and potential for outside exploitation was wildly inaccurate. In fact, the old wounds were healing faster than even the Finns themselves realized; with the onset of a massive contemporary threat from the Soviet Union, those old enmities looked remote and historic.

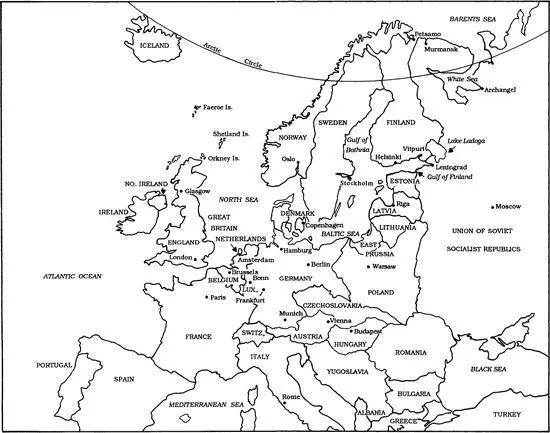

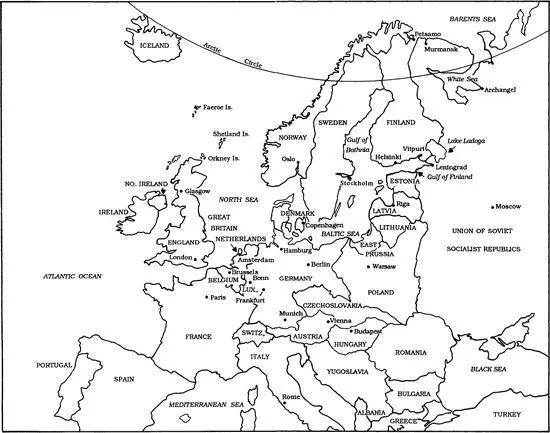

1. Northern Europe in 1939

In April 1938 came the first sign that Russia was no longer satisfied with the status quo of its relations with Finland. An MVD agent named Boris Yartsev, ostensibly a minor diplomatic official in the Helsinki embassy, approached the Finnish foreign minister, Rudolf Holsti, and suggested that it might be in Finland’s best interest to agree to some secret discussions with the Soviet Union, with the aim of “improving relations” between the two countries. The reason, Yartsev claimed, was the gradual worsening of the international situation. The Soviets did not trust Nazi Germany, and if war between those two mighty powers should erupt, a glance at the map would reveal the obvious advantages Germany would gain if Hitler could use Finland as a base for operations against Russia. If such a threat were to develop, Yartsev stressed, it would not be the Red Army’s intention to wait passively behind its fixed defenses but rather “to advance as far as possible to meet the enemy”—a veiled reference to the strategy of preemptive attack. If Finland were prepared to resist German pressure, then Russia would be prepared to extend all possible economic and military assistance. Russia needed some “positive guarantees” from Finland that Germany would never be allowed to use Finnish territory as a springboard to attack the USSR.

Holsti wanted to know what those “positive guarantees” might consist of, but Yartsev had reached the limits of his empowerment to speak. He could not nor would not say more. At this point Holsti brought Finnish prime minister Cajander into the discussions, and both men assured Yartsev that Finland was indeed committed to a policy of strict neutrality and would resist any armed incursion to the best of its ability. Yartsev indicated that Stalin was not likely to be impressed by that statement, given Finland’s military weakness. But if the Finns backed up their protestations with some kind of tangible gesture, it was entirely possible that trade relations between Finland and Russia would suddenly improve. The most suitable gesture would be for Finland to cede, or lease, to the Soviet Union a number of intrinsically valueless islands in the Gulf of Finland along the seaward approaches to Leningrad.

Читать дальше