Mannerheim’s display of pique seems to have lit a fire under Östermann because Finnish activity in the forward zone became much more aggressive on the night of December 5–6. A number of ambitious raids were launched against exposed Russian salients. A couple of these actions stung the Russians badly and inflicted several hundred casualties on them. By December 6, however, there really wasn’t much of a “forward zone” left: only a few shallow strips in front of parts of the Mannerheim Line. Virtually all of the still-committed covering troops had withdrawn back into the line by the end of the day.

If, on the one hand, there had been no smashing Finnish victory, at least there had been no Poland-style breakthroughs, either. And if many units had performed badly in their first encounters with tanks, most of them had rallied quickly and mastered their panic. If the Finns had possessed even a single brigade of modern armor, they could have cut several Soviet formations to ribbons; but tanks were costly items, and Finland’s military priorities were strictly defensive.

It is also possible, as some Finnish historians have suggested, that Mannerheim, old cavalryman that he was, had something of a blind spot about armor. He kept up with modern military theory, he knew all about the blitzkrieg, and he encouraged imaginative tactics for use against tanks. But tanks can also serve in a defensive capacity—as mobile reserves that can be used to add weight and power to local counterattacks, as artillery, as mobile antitank units. Given the constricted area of the Karelian Isthmus, the number of tanks needed was not prohibitively large; thirty or forty would have been a great help. [2] Mannerheim may have learned a lesson from the Winter War, however, because when the Finnish Army went into action again, in 1941, it had lots of tanks, most of them, in fact, reconditioned Russian vehicles captured in 1939–40. They were augmented by some Czech models handed down by the Wehrmacht.

Most important of all, however, by actively engaging the enemy from the first instead of passively waiting behind their fortifications, the Finns gained valuable experience. The most precious datum was the knowledge that the Russians were not supermen—far from it; they were slow, ponderous, unaggressive, and unimaginative. They could be beaten.

The Finns who had fought them in the border zone took that message back into the Mannerheim Line, and as they told their stories, there was a discernible stiffening of resolve along the entire defensive front. The defenders were going to need that resolve because there was a firestorm coming down on their heads like nothing any of them had ever imagined.

So congested and confused were the advancing Russian columns that it took an additional thirty-six to forty-eight hours after the covering troops had disengaged for the Soviet artillery to catch up and dig in. During those first days, a number of local probing attacks were sent against the line, but they were not seriously threatening.

The Russians were, in fact, curiously lethargic and followed a predictable workaday routine. Russian infantry, often riding in trucks, would arrive at their jumping-off points at first light and then move out, not very energetically, in the general direction of Finnish lines. Sometimes by simple weight of numbers they forced the Finns to withdraw from exposed or unsupported positions, but thereafter they did nothing to exploit these little victories. In the afternoon, when the light began to fail, the Russians would withdraw a kilometer or two to the east, dig in behind a wagon circle of tanks, parked with their headlights and machine guns facing out, and build huge campfires. The Finns would then creep forward and reoccupy their positions, usually without interference and often reaping the bonus of discarded Russian equipment or bits of thrown away paper that proved useful to the intelligence staff.

Mannerheim was still unsatisfied. He wanted the Finns to do more, to press forward under cover of darkness and attack the enemy while he was warming himself at his campfires. Most Finnish soldiers lacked either the confidence or the experience to try a night attack, at least at this stage of the fighting. Moreover, early December marks the beginning of the period of maximum winter darkness in these latitudes, and very few flare pistols, star shells, or searchlights had reached the line as yet. One cannot blame the Finnish officers for not wanting to risk shaky troops on nocturnal operations without such things.

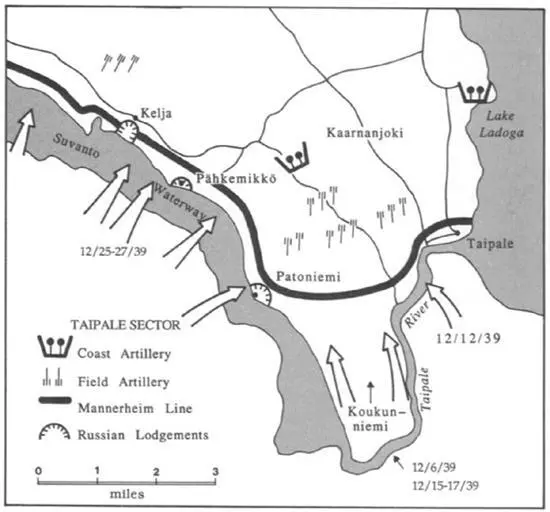

The first major Russian blows did not fall on the “Viipuri Gateway” at Summa but, rather, on the extreme left flank of the Mannerheim Line, in what would come to be known as the Taipale sector, after the small Ladogan fishing village that anchored its right flank. Meretskov knew the Finns would expect him to hit Summa first, and the reasonable assumption was that the defenders had concentrated both their strongest fortifications and their tactical reserves in that part of the line. He therefore resolved to launch a strong feint attack at Taipale, in hopes of drawing off those reserves and softening up the Summa sector.

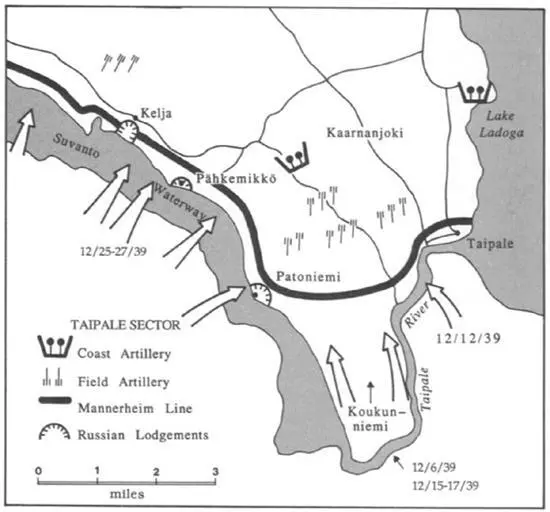

But the Finnish Tenth Division, dug in at Taipale, knew it could count on no significant reinforcements. Mannerheim and his generals knew exactly what Meretskov was up to, and they were not going to shift a single company from Summa if they could help it. The line at Taipale followed the outline of a long, tapering, blunt-ended promontory, bounded on the south by the Suvanto branch of the Vuoksi Waterway and on the north by Lake Ladoga itself. Between the wide Suvanto and the lake ran the narrow Taipale River.

Along the Suvanto sector the Finns enjoyed a slight advantage of elevation and had some dry ground to dig in. Across the base of the promontory, however, the water table was very close to the surface and the entrenchments there were little more than augmented drainage ditches. The narrow tip of the peninsula, called Koukunniemi, was no-man’s-land. The Finns had voluntarily given it up because it was low, marshy, and utterly barren of cover. This was a sensible step to take, for it enabled them to streamline their positions and concentrate their limited strength. They also hoped that, by leaving the cape undefended, they could tempt the Russians into attacking there in strength. The open tongue of land was a killing ground. Every millimeter of it had been ranged by Finnish artillery and a fire plan worked out to bring down destruction on any force that gained a foothold there.

4. Russian Attacks on Taipale Peninsula, December 1939

As soon as their first artillery batteries caught up with them, late on December 6, the Russians moved against Taipale. Their attack began with heavy artillery preparation, a foretaste of what was to come all along the line. After a four-hour bombardment, the Red infantry swarmed forward. They attempted a crossing at the Lossi ferry landing but were thrown back. Just as the Finns had hoped, the enemy did swarm on to the vacant promontory of Koukunniemi, and once they were in the bag, the Finnish artillery plastered that exposed ground with devastating effect. The Russians sustained hundreds of casualties, and the survivors of the barrage fled at the first sign of a counterattack by Finnish infantry.

Skirmishing and artillery duels now flared constantly along the entire Taipale sector as the Russians probed, tested the defenders’ strength, and brought up more guns. The next major Soviet effort against Taipale came on December 14, and by that date patrols and aerial photographs had given the Finns a clear idea of what sort of odds they faced. From December 6 to December 12, only one Russian division was engaged on this front; now a second division was deployed. Russian artillery strength had risen, during that same interval, to fifty-seven batteries, as opposed to the nine motley batteries the Finns could call on.

Читать дальше