The wartime Finnish division had a paper strength of 14,400 men. The average Red Army division was officially supposed to number 17,000, but the varying additions of tank and specialist troops during the Winter War make that figure only a rough approximation.

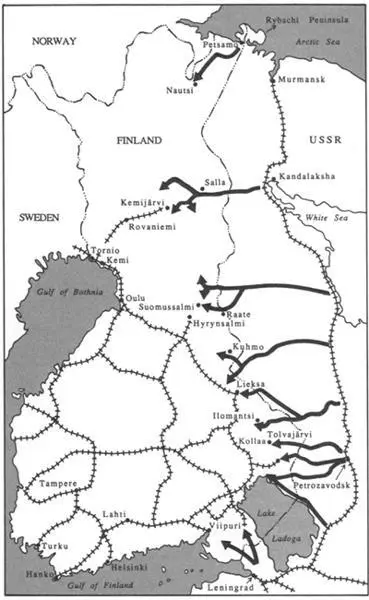

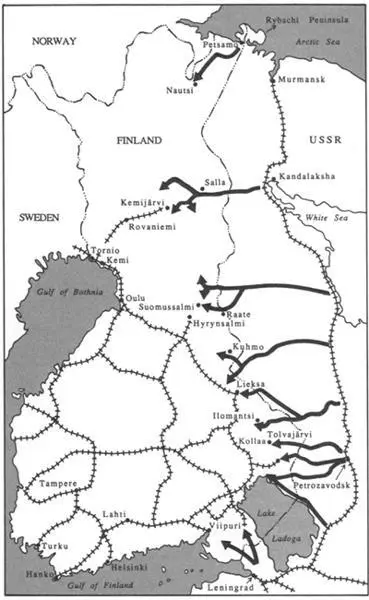

At the beginning of the war, Mannerheim’s forces were deployed as follows:

1. Army of the Karelian Isthmus: Six divisions under the command of General Hugo Viktor Östermann. On the right, the southwest Isthmus, was Second Corps, under General Öhquist, composed of the Fourth, Fifth, and Eleventh divisions, along with three groups of “covering troops” operating forward of the Mannerheim Line in early December. On the left flank, from the Vuoksi Waterway to Lake Ladoga, was Third Corps, commanded by General Heinrichs, comprised of the Ninth and Tenth divisions and one detachment of covering troops.

2. Fourth Corps: Two divisions, manning a sixty-mile line extending in a roughly concave crescent from the north shore of Lake Ladoga, commanded by General Hägglund.

3. North Finland Group: Covering the remaining 625 miles to the Arctic Ocean, this collection of Civic Guards, border guards, and activated reservist units was led by General Tuompo. Its southern unit boundary with Fourth Corps ran through the town of Ilomantsi.

Mannerheim had established his wartime headquarters in the town of Mikkeli (St. Michael). He seems to have liked the symbolism. He knew the place well, for he had mounted his final campaigns against the Reds from there in 1918. Nostalgia and symbolism aside, the village was about equidistant from the Isthmus and from Fourth Corps’s zone of operations and was thus a logical choice. Mannerheim had two divisions in strategic reserve, one near Viipuri at work building fortifications, and the other based at Oulu, on the Gulf of Bothnia. Both units were woefully underequipped with mortars, machine guns, radios, even skis, and not a man could be moved without Mannerheim’s personal order.

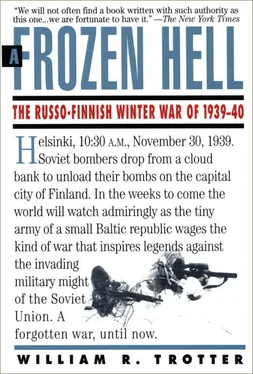

HELSINKI

At 9:20 A.M., November 30, 1939, the first Russian plane appeared over Helsinki. It dropped thousands of leaflets urging the citizens to overthrow the Mannerheim/Cajander/Erkko government, then went on to drop five light bombs in the general vicinity of Malmi Airport.

As dawn gave way to full daylight, the morning sky was bright and clear, except to the south, where a large cloud bank had formed in the direction of Estonia. At about 10:30, the forward edge of those clouds suddenly rippled with light as a wedge of nine Russian planes (SB-2 medium bombers) left cover and leveled off for a run over the capital. The leading aircraft released their first sticks of bombs over the harbor, presumably aiming at the shipping crowded there. All of the bombs fell harmlessly into the water.

Then the formation banked toward the downtown heart of the city, apparently aiming at the architecturally renowned Helsinki railroad station. Although there was no resistance and weather conditions were ideal, the Russians didn’t manage to get a single hit on the station itself. They did, however, thoroughly plaster the huge public square in front of the building, killing forty civilians.

Three planes peeled off and raked the municipal airport, setting fire to one hangar. The Helsinki Technical Institute was badly hit, and several students and faculty were killed. The Russian formation then broke into small groups, and these roamed at will above the city, scattering random bundles of small incendiary bombs, doing little serious damage but causing a chaotic rash of small fires that stretched the city’s fire-fighting resources to the limit. On their way out, the planes took time to strafe a complex of working-class housing units and to drop their last few high-explosive bombs on the inner city, some of which severely damaged the front of the Soviet Legation building.

Then the bombers throttled for altitude, formed into a neat formation again, and flew off to the east, the empty sky behind them dotted with a few puffs of smoke as Helsinki’s antiaircraft batteries clawed after them in vain. None of the flak batteries had opened fire until the last moments of the raid, and not one of their shells came within 1,000 meters of an enemy aircraft. Not until the Red bombers had vanished did the city’s air-raid sirens belatedly start to howl their now-pointless warning.

2. Major Soviet Offensives of November 30-December 1

Another raid, this time by fifteen planes, struck at about 2:30 P.M., after the all-clear had sounded and while the streets were choked with civilian and emergency traffic. Most of the bombs fell at random, but another fifty people died and two or three times as many were injured. All told, Helsinki suffered 200 dead that first day.

On the same morning the Red Air Force launched heavy attacks on Viipuri, on the harbor at Turku, on the giant hydroelectric plant at Imatra, and—for some inexplicable reason—on a small gas mask factory in the town of Lahti.

Out in the Gulf of Finland, landing parties from the Soviet Baltic Fleet occupied without resistance the disputed islands of Sieksari, Lavansaari, Tytarsaari, and Suursaari.

After detouring past craters, corpses, and piles of flaming debris, Gustav Mannerheim’s car pulled up to government headquarters. Inside the Marshal sought out President Kallio and withdrew his resignation. Kallio had been expecting him and, on the instant, activated him as commander in chief of the Finnish armed forces.

By the end of the day, the Finnish government had changed hands. The major instrument of that change was the veteran left-center political leader Väinö Tanner, head of the powerful Social Democrats. Tanner spent most of the day huddled in an air-raid shelter, and he emerged from that experience more convinced than ever that the inflexible nationalistic regime of Prime Minister Cajander and Foreign Minister Erkko would have to yield power. Tanner had already lined up the necessary parliamentary support when he approached Cajander that night, after the civilian government had moved to its wartime headquarters at Kauhajoki, northeast of Helsinki.

To soften the emotional blow, Tanner engineered a symbolic vote of confidence for Cajander in the Finnish Diet, then he took Cajander aside and told him that he had two choices: resign now with honor intact, or suffer the historical shame of being booted out of office in the morning. It was a bitter moment for Cajander: he and Erkko had worked hard to lead the nation through several relatively prosperous years, always with considerable public support for their policies. Now they were being pronounced unfit to lead Finland in time of war. Nevertheless, although there was much hard feeling in private, the public changing of the guard was accomplished with grace and dignity on the part of all concerned.

Tanner himself replaced Erkko as foreign minister. To fill Cajander’s place at the prime minister’s desk, Tanner picked Risto Ryti, president of the Bank of Finland. The new government’s policy was clear: to reopen negotiations and end hostilities as fast as possible. To maximize Finland’s bargaining power, the military strategy would be to hold on to every inch of Finnish soil and to inflict maximum casualties on the enemy—to present Stalin with such a butcher’s bill that he, too, would be eager for negotiations.

While Tanner worked the diplomatic front, Ryti ran the war effort, including the campaign to obtain aid from abroad. He worked closely with Marshal Mannerheim, usually at the Marshal’s headquarters rather than the civilian government’s. Mannerheim refused to leave his command post when there was a battlefield crisis to deal with, which, after the first hours of the war, there usually was.

Читать дальше