Wilson, Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland, 234, 237

Winant, John G., 149-53, 157-59, 182

Winckler, Barbara, 166

Winckler, Charlotte, 165

Winckler, Ekkehart, 165

Winocour, Jack, 496

Winterfeldtstrasse, 359, 457

Wittenberge, 116, 297, 298

Wittingen, 318

Wöhlermann, Colonel Hans Oscar, 110, 397, 398

Wolf, Johanna, 56, 404

Working Security Committee, 151, 156

Wriezen, 265

Wulle-Wahlberg, Hans, 420

Y

Yalta Conference, 101-3, 161-62

agreements violated by Stalin, 162, 164, 235

Younger, Flight Sergeant Calton, 410

Yushchuk, Major General Ivan, 186, 368, 391

Z

Zarzycki, Bruno, 39, 60, 430-32

Zehlendorf, 17, 18, 434, 478, 484-85

Zerbst, 330

Zhukov, Marshal Georgi K., 38, 177, 185, 194, 248 n , 345, 449, 500

background of, 244-45

called to Moscow, 243-51

criticism of, 360-61

in Oder offensive, 347, 350-51, 360-62, 391, 393-94, 412, 472-73

plans attack on Berlin, 21-22, 250-51, 254, 302-3, 352

reprimanded by Stalin, 393-94

Ziegler, SS Major General Jürgen, 397

Zones of occupation, see Occupation of Germany

Zoo, 62-63, 511-12

air raids on, 14, 169

closes, 408

described, 168-71

shelled, 484

Zoo Bunker (Zoo towers), 167-68, 377, 382, 466, 483-84, 514

Zossen, 70, 368

bombing of, 79n

described, 77-79

Heinrici at, 77-90

Russian capture of, 432-34

Russian drive on, 393, 407, 412-13

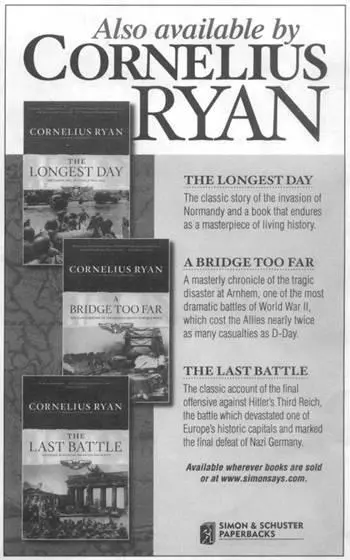

CORNELIUS RYANwas born in 1920 in Dublin, Ireland, where he was raised. He became one of the preeminent war correspondents of his time, flying fourteen bombing missions with the Eighth and Ninth U.S. Air Forces and covering the D-Day landings and the advance of General Patton’s Third Army across France and Germany. After the end of hostilities in Europe, he covered the Pacific war. In addition to his classic works The Longest Day, The Last Battle, and A Bridge Too Far, he is the author of numerous other books that have appeared throughout the world in nineteen languages. Awarded the Legion of Honor by the French government in 1973, Mr. Ryan was hailed at that time by Malcolm Muggeridge as “perhaps the most brilliant reporter now alive.” He died in 1976.

A BRIDGE TOO FAR — 1974

THE LAST BATTLE — 1966

THE LONGEST DAY — 1959

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 1966 by Cornelius Ryan

Copyright renewed © 1994 by Victoria Ryan Bida and Geoffrey J. M. Ryan

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

11 13 15 17 19 20 18 16 14 12

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-18654

ISBN-13: 978-0-684-80329-6

eISBN-13: 978-1-439-12701-8

ISBN-10: 0-684-80329-1

I have not seen the Ehrenburg leaflet. But many of those I interviewed did. Furthermore, it is mentioned repeatedly in official German papers, war diaries and in numerous histories, the most complete version appearing in Admiral Doenitz’ Memoirs , page 179. That the leaflet existed I have no doubt. But I question the above version, for German translations from Russian were notoriously inaccurate.Still Ehrenburg wrote other pamphlets which were as bad, as anyone can see from his writings, particularly those officially published in English during the war by the Soviets themselves, in Soviet War News , 1941-45, Vols. 1-8. His “Kill the Germans” theme was repeated over and over—and apparently with the full approval of Stalin. On April 14, 1945, in an unprecedented editorial in the Soviet military newspaper Red Star , he was officially reprimanded by the propaganda chief, Alexandrov, who wrote: “Comrade Ehrenburg is exaggerating… we are not fighting against the German people, only against the Hitlers of the world.” The reproof would have been disastrous for any other Soviet writer, but not for Ehrenburg. He continued his “Kill the Germans” propaganda as though nothing had happened—and Stalin closed his eyes to it. In the fifth volume of his memoirs, People, Years and Life , published in Moscow, 1963, Ehrenburg has conveniently forgotten what he wrote during the war. On page 126 he writes: “In scores of essays I emphasized that we must not, indeed we cannot, hunt down the people—that we are, after all, Soviet people and not Fascists.” But this much has to be said: no matter what Ehrenburg wrote, it was no worse than what was being issued by the Nazi propaganda chief, Goebbels—a fact that many Germans have conveniently forgotten, too.

The estimated figure of Jewish survivors comes from Berlin Senate statistics prepared by Dr. Wolfgang Scheffler of Berlin’s Free University. They are disputed by some Jewish experts—among them Siegmund Weltlinger, who was Chairman for Jewish Affairs in the post-war government. He places the number who survived at only 1,400. Besides those underground, Dr. Scheffler states that at least another 5,100 Jews who had married Christians were living in the city under so-called legal conditions. But at best that was a nightmarish limbo, for those Jews never knew when they would be arrested. Today 6,000 Jews live in Berlin—a mere fraction of the 160,564 Jewish population of 1933, the year Hitler came to power. Of that figure no one knows for certain how many Jewish Berliners left the city, emigrated out of Germany, or were deported and exterminated in concentration camps.

There was another category of laborer—the voluntary foreign worker. Thousands of Europeans—some were ardent Nazi sympathizers, some believed they were helping to fight Bolshevism, while the great majority were cynical opportunists—had answered German newspaper advertisements offering highly paid jobs in the Reich. These were allowed to live quite freely near their places of employment.

Unser Giftzwerg literally means “our poison dwarf”—and the term was often applied to Heinrici in this sense by those who disliked him.

Zossen was, in fact, heavily bombed by the Americans just seven days before, on March 15, at the request of the Russians. The message from Marshal Sergei V. Khudyakov of the Red Army staff, to General John R. Deane, chief of the U.S. Military Mission in Moscow, now on file in Washington and Moscow, and appearing here for the first time, is an astonishing document for the insight it offers into the extent of Russian intelligence in Germany: “Dear General Deane: According to information we have, the General Staff of the German Army is situated 38 kms. south of Berlin, in a specially fortified underground shelter called by the Germans ‘The Citadel.’ It is located… 5½ to 6 kms. south-southeast of Zossen and from 1 to 1½ kms. east of a wide highway… [Reichsstrasse 96] which runs parallel to the railroad from Berlin to Dresden. The area occupied by the underground fortifications… covers about 5 to 6 square kilometers. The whole territory is surrounded by wired entanglements several rows in depth, and is very strongly guarded by an SS regiment. According to the same source the construction of the underground fortification was started in 1936. In 1938 and 1939 the strength of the fortifications was tested by the Germans against bombing from the air and against artillery fire. I ask you, dear General, not to refuse the kindness as soon as possible to give directions to the Allies’ air forces to bomb ‘The Citadel’ with heavy bombs. I am sure that as a result… the German General Staff, if still located there, will receive damage and losses which will stop its normal work… and [may] have to be moved elsewhere. Thus the Germans will lose a well-organized communications center and headquarters. Enclosed is a map with the exact location of the German General Staff [headquarters].”

Читать дальше