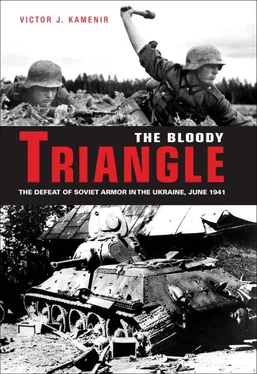

Arrests were not limited to faculty but included students as well. Future marshal of the Soviet Union Ivan Khristoforovich Bagramyan, whose memoirs will be extensively quoted in this work, was a student at the General Staff Academy during the purges. Normally, the first step before arrest was denouncement at a Communist Party meeting, followed by expulsion from the Communist Party. At one such meeting, Bagramyan was accused of being a former member of Dashnaks, an anti-revolutionary Armenian military formation during the Civil War. Despite documented proof that Bagramyan, in fact, fought against this organization, he was expelled from the Communist Party and was expecting an arrest to come at any minute. Following a friend’s advice, Bagramyan appealed the expulsion and, astonishingly, was fully cleared and reinstated. [5] Grigorenko, 90.

However, a black mark stuck to him, and this episode slowed down his rise through the ranks before the war.

During the late 1920s, Bagramyan attended an advanced course for cavalry officers in which two of his classmates were the future Marshals Georgiy Zhukov and Konstantin K. Rokossovskiy. Rokossovskiy was later arrested for his association with Marshal Tukhachevskiy. He underwent severe beatings and tortures at the hands of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD) interrogators and, during multiple brutal beatings, all of his teeth were knocked out. Miraculously, Rokossovskiy was released shortly before the war and appointed to command a mechanized corps. Some men, like still-pugnacious Rokossovskiy, with his mouth full of gold teeth to replace the ones knocked out by NKVD men, survived the purges with their characters intact. Others, like the former Chief of General Staff General Kiril A. Meretskov, emerged from the NKVD basements broken men. During his two months of imprisonment, Meretskov’s tortures were so particularly brutal that even the sinister NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria described them as a “meat grinder.” Even though released and reinstated like Rokossovskiy, Meretskov was nonetheless a changed man, meek and indecisive.

Men, who unflinchingly faced death on multiple battlefields during World War I and the Russian Civil War, were tortured into signing false confessions, implicating themselves and other innocent men for nonexistent crimes. The most common charge was “agent of foreign power.”

The havoc created in the Soviet military by the purges was terrifying. Men who replaced those shot or dismissed the previous year would find themselves similarly dealt with, and their successor would often share the same fate. The extraordinary upheaval moved men several steps up the command chain in a space of a year or two, resulting in young and inexperienced officers promoted far beyond their competency and ability.

The effect of the loss of so many senior officers had a tremendous effect on Soviet enlisted personnel. The generally poorly educated Soviet enlisted men were more susceptible to trust Communist Party propaganda. Many of them believed that their former superior officers were traitors and “enemies of the people,” which undermined their trust in their commanding officers and drastically lowered discipline and combat readiness in the armed forces.

In the Soviet Far East, another charismatic Soviet commander, Marshal Vasiliy Blyukher, was in a position of great power, far from Moscow’s reach. This popular and capable commander shared Tukhachevskiy’s fate and was executed. The officer ranks under his command suffered particularly heavy cleansing. Then-Colonel Grigorenko, upon assignment to the Far East in 1940, found the situation to be dismal:

Almost two years had passed since the mass arrests had come to an end, but the command pyramid had not yet been restored. Many positions remained unfilled because there were no men qualified to occupy them. Battalions were commanded by officers who had completed military schools less than a year before. Some battalion commanders had completed only courses for second lieutenants, and their experience had been limited to several months of command of platoon or company…. In the 40th Infantry Division, not only had the officers of divisional and regimental administrations been arrested, but also the commanders of battalions, companies, and platoons. [6] Ibid., 111.

Stalin’s purges cost the Soviet military close to fifty thousand officers, mostly in field-grade and general ranks, who were executed, imprisoned, or cashiered. While some of them were nothing more than Communist Party hacks in uniform, an overwhelming greater part of them were men with military experience. A majority of them saw service with the old Russian Imperial Army and fought during World War I and the Russian Civil War. In the aftermath of World War I and immediately following the communist takeover of Russia, virtually all the former czarist officers were driven out of the military. Listed among “class enemies,” allegedly hostile to the nascent Communist regime, the officers of the old army were slaughtered in large numbers during the Red Terror. Numerous others immigrated, joined the burgeoning counter-revolutionary “White” royalist formations, or melted into civilian society.

In 1918, as the young Communist government was faced with the life-or-death struggle against armed insurrections of various anti-Bolshevik military formations, foreign interventionists, and home-grown peasant rebellions, the need for qualified officers to lead the brand-new Red Army became dire.

Recognizing the severity of the situation presented by a lack of trained cadres, first commander of the Red Army Leon Trotskiy instituted a wide-scale program of bringing the former czarist officers back into uniform under unobtrusively sounding title of “military specialists.” The purist communists howled at such pollution of proletarian ranks, but Trotsky dug in his heels, and eventually over two hundred thousand former officers were re-integrated into the military. Some went willingly, some not, and more rejoined out of a need to make a living. In many cases, these officers’ participation was obtained only by the Reds holding their families as hostages to ensure men’s cooperation.

However, a majority of officers who rejoined the ranks were not the same men who led the Russian army at the start of World War I. The old, mostly aristocratic, officer corps of 1914 was largely wiped out during the first bloody years of the conflict. They were replaced overwhelmingly by men from the middle class and often from the working class. Many among this new generation of officers were more sympathetic, or simply nonhostile, to the Communist regime. Yet more men served out of sense of patriotic duty to Russia, regardless of political views of those at the helm. A prime example of such men was the Russian General Staff, almost to a man joining the Red Army out of sense of serving their country. Such “military specialists” provided the needed backbone, and some of them went on to distinguished careers in the Red Army. Some, like Zhukov, a former noncommissioned officer (NCO), and Tukhachevskiy and Boris M. Shaposhnikov, former aristocratic officers, went on to gain the highest ranks and top positions in the Soviet military.

Attempting to alleviate shortfall of officer cadres before the war, the Red Army leadership increased the number of officer schools, shortened the course of study at the existing ones, and called up numbers of reservist officers. According to Colonel Bagramyan:

From 1939 to 1940, 174,000 reserve officers were called to active duty. Numbers of students at military academies doubled. In 1940 alone, 42 new military schools were created…. Numbers of students at military schools rose from 36,000 to 168,000 men. [7] In the Soviet/Russian military, the term “military academy” is applied to learning institutions for officers of field and general grades. The term “military school” is applied to a primary officer training institutions producing lieutenants.

All military schools switched from three-year curriculum to two years. At the same time, numerous courses for junior lieutenants were organized….

Читать дальше

![О Генри - Социальный треугольник [The Social Triangle]](/books/405340/o-genri-socialnyj-treugolnik-the-social-triangl-thumb.webp)