The photographers moved into place. I was determined to show no emotion, whatever the sentence. But my fingers gripped the railing even tighter.

“At the same time,” the judge continued, “weighing all the circumstances of the given case in the deep conviction that they are interrelated, taking into account Powers’ sincere confession of his guilt and his sincere repentance, proceeding from the principles of socialist humaneness, and guided by Articles 319 and 320 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Soviet Federated Soviet Republic, the military division of the USSR Supreme Court sentences:

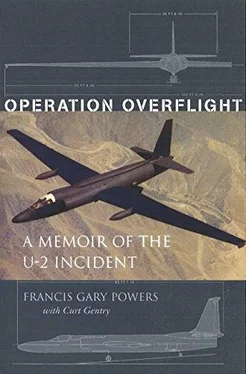

“Francis Gary Powers, on the strength of Article 2 of the USSR Law ‘On Criminal Responsibility for State Crimes,’ to ten years of confinement ….”

I didn’t hear the rest. I looked for my family, but in the confusion couldn’t see them. All over the hall people had stood and were applauding. Whether because they felt the sentence suitably harsh or humanely lenient I did not know.

From the moment Rudenko had said he would not ask for the death sentence, I had expected the full fifteen years.

Only as I was being led from the courtroom did the full impact of the sentence hit me.

Ten long years!

My mother, father, sister Jessica, Barbara, and her mother were already in the room when I was ushered in. I couldn’t help it. Seeing them, I broke down and cried. They were all crying too.

My hopes for a private meeting were overly optimistic. Besides four guards, two interpreters, and a doctor, there were also, for the first few minutes, a half-dozen Russian photographers.

A table had been set up in the center of the room, with sandwiches, caviar, fresh fruit, soda, tea. None of us touched it. We just looked at each other. For three and a half months we had been awaiting this moment, fearful that it might not occur, but still saving up things to say. Now that it was here, they were all forgotten. There would be long silences; then everyone would try to talk at once. I hadn’t realized how much I’d missed hearing a Southern accent, until hearing five of them.

It was mostly small talk, but I’d had very little of that. Family news. Messages from sisters, nephews, nieces. A report on how our dog, Eck, was adjusting to Milledgeville. Decisions—whether to sell the car, rent or buy a house, ship the furniture from Turkey.

I now learned the rest of my sentence, which I had not heard in the courtroom. “Ten years of confinement, with the first three years to be served in prison.” This meant, one of the interpreters explained, that after three years in prison I might be assigned to a labor camp in some obscure part of Russia. With permission, my wife could live nearby and make “conjugal visits.” There was also the possibility, one of the American attorneys had told my father, that I could apply for the work camp when half my prison time was served, in other words in a year and a half. And my sentence started from the moment of my capture, which meant I had served over three and a half months of it already. Of course, there were still other possibilities. They were appealing to both President Brezhnev and Premier Khrushchev. They had tried to see the premier, but he was vacationing at the Black Sea, although his daughter, Elena, had attended the trial.

We grasped and held tightly like precious things the little bits of hope in the sentence. But the words “ten years” hung over the room.

We tried to make plans, but too much remained unknown. Barbara wanted to stay in Moscow, possibly get a job at the American Embassy. I was against that. There was no assurance they would let her visit me, and I would soon be transferred to a permanent prison outside Moscow; I hadn’t been told where or when.

I learned another bit of news. The Russians had shot down an RB-47 on July 1, somewhere in the Barents Sea. The Soviets said it had violated their territory; the United States declared it hadn’t. The pilot had been killed; the two surviving crew members—Captains Freeman B. Olmstead and John R. McKone—were being held by the Russians. There was no word yet as to whether they would be brought to trial.

I knew neither man. But I knew how they felt.

My mother had brought me a New Testament. One of the guards took it; it would have to be examined, the interpreter explained. Barbara brought a diary, which I’d asked for in one of my letters. That was taken too. I wondered whether my captors were worried about hidden messages or whether they thought my own family was trying to smuggle poison to me.

Noticing I was without a watch, my father offered me his. No, I told him, they probably wouldn’t let me keep it, and if they did, I’d only be watching the time.

My mother was concerned about my loss of weight. I was concerned about their health. All showed the tremendous strain they had been under, Barbara especially. Her face was very puffy, as if she had been crying or—I hated to think it—drinking heavily.

The friction between Barbara and my parents was obvious, though the cause remained a puzzle. I was determined that if allowed to see them again—the interpreter had said this might be possible—I would try to arrange separate visits.

The interpreter warned us that our hour was nearly up.

I had a message for the press, I told them. Grinev’s denunciation of the United States had come as a shock to me. I had not known what arguments he would use, until hearing them in court. I repudiated them, and him, entirely. As for his statement that I might remain in the Soviet Union, I would leave Russia, and gladly, the minute they let me do so. I was an American, and proud to be one.

The hour was up. The guards led me away.

That evening the guards brought me the New Testament and the diary. The latter was a five-year diary. I would need two of these, I realized, before my sentence was completed.

My first entry was brief, purposely. I was afraid that once starting to write, I would release a well-spring of pent-up emotions.

August 19, 1960: “Last day of trial. 10 yr. sentence. Saw my wife and parents for one hour.”

The nineteenth was a Friday. Saturday and Sunday were very hard. Everything went on as usual in the prison, yet, knowing I had ten years to look forward to, everything was subtly, immutably changed.

Looking back, I could see I had brainwashed myself into anticipating the death sentence. Perhaps it was a trick of the mind, an escape device. Perhaps unconsciously I had realized all along that for me the worst possible punishment would be a long imprisonment.

On Monday, August 22,1 was taken to the Supreme Court Building in central Moscow for my last meeting with my mother, father, and sister, during which my father several times referred cryptically to “other efforts” being made to secure my release.

I had no idea what they were. But he obviously did not wish to elaborate, with my jailers present.

He was extremely angry with Grinev. McAfee had sent him, weeks ago, a detailed brief with suggestions for my defense. He had given no indication of having read it.

I said that I was not exactly happy with his “defense” myself, that Grinev had made it through the trial with a perfect score—not a single objection, not one statement which contradicted the prosecution.

As my father had already told the press, he was convinced that the Russians wouldn’t make me serve my full sentence. If for no other reason, they wouldn’t want the expense of feeding me.

I hoped he was right, but was afraid it wouldn’t be quite that simple.

It was a difficult parting: my parents leaving their only son in this hostile land; I was not sure, considering their age and health, whether I would see either of them again.

After they left, Barbara and her mother came in. They brought along a United States Embassy “News Bulletin,” with quotations from President Eisenhower’s last press conference. The President regretted “the severity of the sentence,” noted that the State Department was still following the case closely and “they do not intend to drop it,” and added that there was no question of my being tried on my return to the United States. As far as the government was concerned, I had acted in accordance with the instructions given me and would receive my full salary while imprisoned.

Читать дальше