I could only imagine the pressures they had been under. Yet I couldn’t help feeling let down. At this, of all times, I wanted them to be united.

Having this to worry about, as well as the trial, did nothing to help my frame of mind.

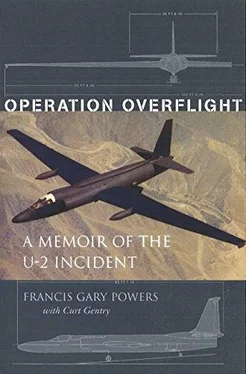

On August 10 Grinev brought me a copy of the indictment. Drawn up by Shelepin, had of the KGB, on July 7, Rudenko, as prosecutor, had approved it on July 9, the same day as Grinev’s first visit: yet they had waited more than a month—until just seven days before the start of the trial—to show it to me. Grinev claimed to have received his copy only that day. Although I said nothing, I frankly didn’t believe him. I later leaned it had been released to Reuters on August 9 and appeared in most newspapers before I saw it.

Typewritten, single-spaced, it ran to seventeen pages. As a legal case it appeared to this layman as sound as any could possibly be. It contained quotes from my interrogations, President Eisenhower’s admission that he had authorized the flights for espionage purposes, testimony from the rocket crew who shot down the plane and the people who detained me. It itemized such physical evidence as maps, photographs of important installations, recordings of Soviet radio and radar signals. It cited Soviet and international law, making it clear that espionage and unauthorized intrusion into the airspace of a sovereign country were crimes in any land.

But it went beyond that. It was, from the first page to the last, a propaganda attack on the United States. It accepted as fact what was in reality conjecture: that the flight had been sent to wreck the Summit talks. It used prejudicial terms such as “gangster flight” and “brazen act of aggression.” It quoted in detail the official lies told by the United States before Khrushchev revealed the capture of the pilot and plane, extraneous material that would be inadmissible in any Western court. It drew unwarranted conclusions, as when it spoke of my “espionage activities” as “an expression of the aggressive policy pursued by the government of the United States.”

Once finished reading it, I realized the trial would not be the USSR v . Francis Gary Powers, but the USSR v . the US and, incidentally, Francis Gary Powers.

But only one defendant would be in the dock, facing the prospect of a death sentence.

And for legal defense he would be completely at the mercy of a man he couldn’t trust.

Exactly what would my defense be?

Grinev was vague. That would depend in large part on the prosecution’s case. Since, from the indictment, this appeared quite solid, he would have to rely heavily on those mitigating circumstances which, he hoped, might cause the court to lessen punishment. Reading from the appropriate code, Article 33 of the 1958 Fundamental Principles of Criminal Law, he cited these. Many were not applicable to my case; the relevant ones included truthful cooperation during interrogation and trial, voluntary surrender and admission of guilt, and “sincere repentance.”

This phrase had been drummed into me even during the interrogations. It was extremely important, Grinev said. I would be asked during the trial whether I was sorry for my action. Upon this answer alone could depend the severity of my sentence.

I thought about it. I was sorry—sorry I had made the May 1 flight; sorry I had been shot down; sorry I was a prisoner having to undergo trial; sorry that as a result of my flight the Summit talks had collapsed. Eisenhower’s visit to Russia had been canceled, and the United States placed in an embarrassing position; sorriest of all that the flight had not been successful, in which case none of this would have happened.

Yes, I could say it, if my life depended on it, as long as I did not have to define too closely what I meant.

Grinev had been given transcripts of the interrogations. We went over them, checking the references in the indictment. I had expected him to ask me a number of questions. But there were very few, either in this or later sessions.

Back in my cell, I reread the indictment carefully, the first time just to see what news I could glean about happenings in the world outside.

But there was little there beyond what I already knew. Though the collapse of the Summit was mentioned, there were no details as to exactly what had occurred.

Both Herter and Nixon were quoted as indicating that the overflights would continue. There was, in the indictment, no statement otherwise. This disturbed me greatly. In some way I would have to get over in the trial that I had been hit while flying at my assigned altitude, that all talk of engine trouble and descending to a lower altitude was false.

I was struck with the sixty-eight-thousand-foot figure. However, maybe I could use that advantageously. If given the chance, I decided to stress that I had been hit at “maximum altitude, sixtyeight thousand feet,” hoping the CIA would realize by “maximum altitude” I meant I was flying exactly where I was supposed to when the explosion occurred. For me to say I was flying at my “assigned altitude” would imply the plane could fly higher, which was true.

If I could get that message across, the trial, for all its propaganda value, would have served one positive purpose. It could be the means for saving the lives of other pilots.

There was no mention of “Collins” in the indictment. Nor had there been in the excerpt from Khrushchev’s speech read to me. That was one of the first things I’d hoped would come out, but apparently it hadn’t. Somehow I would have to get that in too, as a message to the CIA that I hadn’t told everything.

Shouldn’t we rehearse my testimony, go over what I should or shouldn’t say?

That wouldn’t be necessary, Grinev said. The same questions asked during the interrogations would be asked during the trial. So long as I stuck to my earlier answers, there would be no problem.

However, we would have to work on my “final statement.”

I didn’t like the sound of that.

Unlike American law, which permitted the prosecution the final summing up, Soviet law allowed the accused the last word in his own defense. This would be a short statement, which I could read. The important points to be made, Grinev noted, were: I realized I had committed a grave crime; I was sorry for having done so; and I asked the court to realize that the real criminals responsible for my flight were those persons who formulated the aggressive, warmaking policies of the United States.

I told him that I would admit to committing a crime, since under the law I had; that I would say I was sorry, if that was essential to my defense. But I refused to denounce my own government.

It would help my case greatly if I did this, he observed.

I didn’t care.

Despite his arguments, I stuck to my resolve.

It seemed to me we were overlooking some other possibilities. I was not an attorney, but wasn’t there a difference between attempting to commit a crime and actually committing one?

What did I mean?

I was guilty of violating Soviet airspace. Granted. But since none of the data I collected had ever left the Soviet Union, was I guilty of espionage?

Grinev rejected the argument, for what were probably valid legal reasons. All the same, I wanted that point in the statement: none of the information collected during the flight had reached a foreign power, the Soviets had seized it all, and therefore no one had been harmed by my act.

After some grumbling, Grinev let me add it. We worked over the wording of the statement for some time. In fact, we spent almost as much time on those few lines as the rest of my defense.

Both prior to and after the trial there was considerable discussion in the United States as to whether I was actually guilty of violating Soviet airspace, the argument being that as in maritime law, with its twelve mile limit, there must be some boundary beyond which airspace no longer belongs to a single country, that the U-2, flying at sixty-eight thousand feet, or nearly thirteen miles above the earth, might well be considered outside this invisible border. Unfortunately, not having my own attorney, and denied access to U.S. newspapers and magazines, I wasn’t aware of this as a possible defense. However, in all likelihood the court wouldn’t have even considered this argument, since Soviet law is quite firm in claiming sovereignty over all air above the Soviet Union.

Читать дальше