While I was most anxious to read the newspapers, I came to dread the sight of them.

“See,” Major Vasaelliev would say, brandishing a paper, “there’s no reason for you to withhold information. We’ll find it out anyway. Your press will give it to us.”

Often they did. From American newspapers they learned that Watertown was in Nevada, not Arizona; that flights had been made from English bases; that the U-2s were used to measure fallout from Soviet hydrogen-bomb tests.

“Did you know that President Eisenhower personally authorized the flights over Russia?”

“No, I didn’t. Is that true?”

A trick? Or had the incident become much bigger than I suspected?

With the release of the news, there was another change: gradually nature took over, and I began to eat again. At first it was only a cup of yoghurt at breakfast and lunch, but before long I was even trying the foul-smelling fish soup. Though I never found any pieces of fish in it, from the aroma it was obvious a very ripe one had at least swum through.

I estimated my weight loss to be between ten and fifteen pounds. The heart palpitation remained, however, and that worried me.

As did what was going on in the United States.

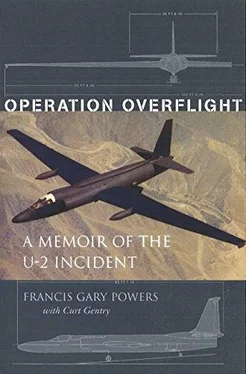

Toward the middle of May, I received additional clues. I was taken out of the prison for the second time, to examine the wreckage of the plane. A display had been set up in a building in Gorky Park. On the walls were large signs in Russian and English, the latter reading: THIS Is WHAT THE AMERICAN SPY WAS EQUIPPED WITH; POWERS FRANCIS GARY THE PILOT OF THE SHOT AMERICAN PLANE; AMMUNITION AND OUTFIT OF THE AMERICAN SPY. Below the signs were displays with my maps; identification; parachute, helmet, pressure suit; survival gear—knife, pistol, ammunition, first-aid kit.

The poison pin was prominently displayed. As were the gold coins and flag reading “I am an American…”in fourteen languages.

Accompanied by an interpreter, stenographer, and a dozen technical experts, I was questioned about each piece of equipment. If it was a standard aircraft part, such as the tachometer, I’d identify it readily. But if part of the special equipment, I’d examine it curiously, as if seeing it for the first time.

And in a sense I was. Never before had I realized how identifiable everything on the plane was. The engine was stamped “Pratt & Whitney”; the camera bore, in addition to its model number, focal length and other specification, the name plates of its U.S. manufacturers; the destruct device was labeled “DESTRUCTOR UNIT, Beckman and Whitley, Inc.,” with the penciled-in date on which it had been received at Incirlik—August, 1959; the radio parts had the trademarks of General Electric, Sylvania, Raytheon, Hewlett-Packard, and others.

Nor was it surprising that they kept insisting I was military. The granger was stamped “MILITARY EQUIP.” A sign under the fueling hatch read:“Fuel only with MIL-D-25524A. Permission to use emergency fuel and climb limitations must be obtained from Director of Materiél.”

No effort had been made to disguise the nationality of the plane. Yet, had the destruct device been used, only a small portion of the aircraft, that containing the surveillance equipment, would have been destroyed. Again it seemed no one had really considered the possibility the plane might go down in hostile territory.

The aircraft itself was a mess, some parts missing entirely. The instrument panel revealed indications of a fire in the cockpit, but apparently a small one, since the maps and other papers were merely singed. The wings and tail were displayed separately from the battered fuselage. I was especially interested in examining the tail, to determine whether there was evidence it had been shot off.

But there were no scorch marks, and the paint was intact.

Everything I saw confirmed my belief that the aircraft had not been hit, but disabled by a near-miss.

Seeing the display, I no longer had any doubt that the Russians were exploiting the incident for maximum propaganda value.

From being worried that no one knew I was alive I had gone full circle to being much too well known. I was not at all sure it was a desirable change.

Shortly after this I was informed I would be tried for espionage under Article 2 of the Soviet Law on Criminal Responsibility for Crimes Against the State. Maximum penalty, seven to fifteen years’ imprisonment, or death.

This aroused no great hope. Before, they could have killed me and no one would have been the wiser. Now they would have to observe the amenities. But the end result would be the same. After a secret trial, I would be shot.

Could I see an attorney now? The investigation is not yet completed. When will it be completed? When we have learned everything we wish to know.

With the press each day adding to their knowledge, I knew that sooner or later they would succeed in trapping me in one or more lies. Should that happen, they would question everything I had already told them. Thus far I had succeeded in withholding the most important information in my possession. But this didn’t mean I could do so indefinitely. There were other ways to make me talk.

One reason I was so concerned was an incident that had occurred a few nights earlier.

Because the bed was so uncomfortable, I always slept fitfully. Very late that night I had rolled over and opened my eyes, to find one of the guards in my cell. It startled me. Seeing I was awake, he picked up my ashtray, indicating it was smelling up the cell. Another guard was standing in the doorway. After handing it to him to empty, the first guard then returned it to the table, closed and locked the door. I returned to sleep, only to reawaken sometime later, in a haze, seeing him there again. This time he left without explanation.

Nothing like this had happened before. Once locked in my cell at night, I had been left alone. It bothered me. Had I dreamed it? No. There was the empty ashtray. Perhaps his excuse was true. But if so, why had he returned? Since, so far as I knew, neither guard spoke English, the idea that I was talking in my sleep and they were trying to listen seemed unlikely, as did the possibility that they feared I had obtained a weapon or some other contraband and were searching my cell. Still another explanation occurred to me. That I might have been drugged. For the first time, I seriously wondered.

The incident remained unexplained. But it made me more anxious than ever that they not doubt my story.

My interrogators now held most of the cards. They knew what had happened since my capture. I didn’t. Each new question increased the possibilities of contradiction, exposure. In some way I’d have to further limit those possibilities.

Notification of the pending trial gave me the excuse I needed. Since I was to be tried for my May 1 activities, I now refused to answer any questions, of whatever kind, on anything happening prior to that date.

This would count against me in the trial, they warned. Reading the appropriate section of their criminal code, they pointed out, as they had on many previous occasions, that the only possible mitigating circumstances in my case were: (1) voluntary surrender; (2) complete cooperation; and (3) sincere repentance.

I had surrendered voluntarily. But as for the last, I had already repudiated that.

Earlier in the questioning, they had asked me if, having it to do over, I would have made the flight. Yes, I replied, were it necessary for the defense of my country.

Since I was unrepentant, the only things now in my favor were my voluntary surrender and complete cooperation.

I stuck to my resolve. I would discuss nothing that happened prior to May 1.

Perhaps it was in an attempt to change my mind that they now decided to make a radical departure.

Читать дальше