We didn’t try to second-guess. We followed instructions.

Briefings were concerned primarily with navigation, and little else. I had anticipated that once overseas the question we had been avoiding would be asked and answered. It wasn’t. Nor did the pilots discuss it among themselves. Perhaps, almost unconsciously, we thought that to do so would bring bad luck.

The intelligence officer did mention in one briefing session that cyanide capsules would be available if we wanted them. Whether we did or did not choose to carry them was up to us, but, in the event of capture we might find this alternative preferable to torture.

The lessons of Korea were still fresh in mind.

The last item put on the plane before each overflight and the first taken off on its return was the destruct unit.

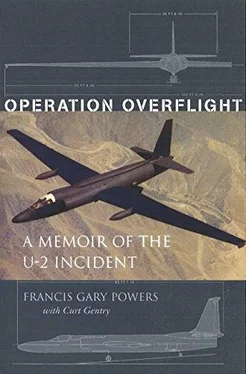

Easily the most enduring myth about the U-2 flights concerns this mechanism, which has engendered an apocrypha so vast it seems a shame to blow it up.

First advanced by the Russians, and later picked up and made much of by certain American writers, was the claim that U-2 pilots were worried that if the device had to be used the CIA had rigged it in such a way that it would explode prematurely, thus eliminating, in one great blast, all incriminating evidence, plane and pilot.

One simple fact quite thoroughly dispels this imaginative fiction. Prior to each and every overflight, maintenance personnel tested the timer. It was a standard part of the preflight check.

Pilots could supervise the testing if they wished to; usually we didn’t bother. We knew and trusted our ground crews. More often than not, these men were close friends (some remain so today). Had such a thing as rigging of the device even been suggested, they were not the type of people to remain quiet about it.

That the device was tested was not because of any suspicion that our employers intended to do us in, but because, as previously noted, there was a slight variance in the allotted time on some units. We were never sure which unit would be used. In a situation where a few seconds could mean life or death, it was imperative not only that we be sure that the timer was working properly but also that we know the exact seconds’ leeway between flipping the switches and the actual explosion.

As for the pilots being nervous about the device, this was quite true. We had also been nervous in the Air Force when flying with payloads. In each case there were a number of safeguards to forestall accidental detonation. But in both we were still flying with a bomb, and there was always the possibility—whether real or imagined, the fear existed—that a small electrical spark might accidentally bypass the most carefully planned circuitry. Neither was especially conducive to peace of mind.

The evening before the flight, I went to bed early. Although it was November, Turkey, being situated on the Mediterranean, had a warm climate almost year round. Made uncomfortable by both the temperature and the unusual hour, I tossed and turned.

The only difference between this and other flights I had already flown, I told myself, was that this would take a little longer and I’d be seeing a different country.

I wasn’t fooling myself. Sleep came hard, even with a couple of sleeping pills.

At five A.M. I was awakened and went to breakfast, after which I reported to Prebreathing to “get on the hose” and suit up. Because of the bulkiness and tightness of the suit, the latter required assistance. During the next two hours I restudied my maps. The routes were color-coded, in blue, red, and brown. Blue indicated the general route, along which some deviation from course was permitted. Red lines marked target areas and were to be flown exactly on course if possible. Alongside were marks indicating where specific photographic and electronic equipment was to be switched on and off. Brown lines denoted routes to alternate bases, if for some reason I couldn’t return to Incirlik.

Following a last-minute briefing on the weather, the intelligence officer asked me if I wanted to carry a cyanide capsule.

I shook my head. Not for any profound reason, rather one that in retrospect sounds a trifle silly. I was afraid the capsule might break in my pocket, and I wanted to avoid the risk of accidental contact.

The plane was already on the runway.

The suit was so cumbersome I had to be helped up the ladder into the cockpit. Once in, it was as snug as always. There was little room for movement.

After the ladder was pulled away, I started the engine. The U-2 has a whine all its own; no matter how many times heard, it thrilled me. This time the feeling was not unmixed with nervousness.

Checking the oil, fuel, hydraulic pressures, the EGT, the RPM, I closed the canopy, locking it from the inside, and turned on the pressurization system.

On signal, I began moving down the runway, pogos falling away the instant the plane left the ground. The ascent, sharp, rapid, started moments later and continued until the base was a tiny speck on the landscape below.

Reaching assigned altitude for this particular flight (it varied), I leveled off.

Periodically I checked the instruments, warning lights and gauges, the clock on the instrument panel.

Exactly thirty minutes after takeoff I reached for the radio call button.

Too close to Russia for voice contact, we had devised a code.

If everything was going well and I planned to continue the flight, I was to give two clicks on the radio.

Since I was still within radio range, this would be picked up back at base.

As acknowledgment, they would click once, indicating message received, proceed as planned. Or they would click three times, indicating that the flight had been scrubbed and I was to turn around and return to base immediately.

This would be the last radio contact until my return.

I clicked twice.

After a moment there was a single click in acknowledgment.

I continued the flight, crossing the Turkish border between Black and Caspian seas and penetrated Russian air space.

There was no abrupt change in the topography, yet the moment you crossed the border you sensed the difference. Much of it was imagination, but that made it no less real. Knowing there were people who would shoot you down if they could created a strange tension. I’d never flown combat; perhaps the feeling was the same. But I thought not. In combat you knew what you were up against. Here you were apprehensive of the unknown. It was the not knowing that got to you.

Were they even aware that I was up here? At this altitude the U-2 couldn’t be seen from the ground, and, above ninety percent of the earth’s atmosphere, conditions were such that jet contrails usually did not form. As for Russian radar, we were, at this time, skeptical of its capabilities, doubtful that it could even pick us up at this height.

Were they, at this very moment, trying to bring me down? The view from the U-2 is restricted. Although you can see miles in front and to the sides, to look down, immediately below, you have to use a view sight, similar to an inverted periscope. From what I could see of the air and ground below, there were no clues. No signs of rockets. No jet condensation trails. Nothing that resembled unusual activity.

Fortunately, just piloting the aircraft and fulfilling the requirements of the mission was a full-time job. Checking the RPM, the EGT, the compass, the fire warning lights, the artificial horizon; watching the ever-critical air speed; homing in on Soviet radio stations; compensating for drift; flipping switches on and off: these were clear and sharply defined things. This was the reality. But the uneasiness remained, like the overlay on a map.

And it would remain throughout this and all other overflights.

Читать дальше