The children's flight to Bath suggested to Whicher that Constance and William were peculiarly unhappy, and capable of acting on that unhappiness. It showed that they could make secret plans and see them through, that they were capable of disguise and deceit. Most significantly, it pointed to the privy as the children's hideway, the place in which Constance disposed of evidence and took on a new identity. In his reports, Whicher drew attention to 'the circumstance of the body being found in the same privy in which she cast her female apparel and hair before absconding from the home . . . disguised as a boy, previously having made a portion of the male attire herself, which she concealed in a hedge some distance from the house until the day of her departure'. The day she ran away could be construed as a step towards the murder of Saville.

Whicher worked alone that week. He 'has been actively and assiduously pursuing his inquiries', reported the Somerset and Wilts Journal , 'making no confidants, unless, indeed, Mr Foley be one. He has been plodding on, visiting for himself, and conversing with, all the persons engaged in this catastrophe, and following up, to its utmost, every gleam of light which might be seen to break in upon it.' The Western Daily Press described the detective's investigations as 'energetic' and 'ingenious'.

Whicher kept quiet about what the house-to-house interviews turned up. Heput out word to the local press that he was 'in possession of a clue by which the mystery will shortly be unravelled', which was dutifully reported by the Bath Chronicle . This was anoverstatement- what he had was a theory - but it stood a chance of rattling the culprit into a confession. The Bristol Daily Post was sceptical about the likelihood that Whicher would succeed: 'it is hoped, rather than expected, that his sagacity may unravel the mystery'.

'Sagacity' was a quality frequently attributed to detectives, in newspapers and in books. The Times referred to Jack Whicher's 'wonted sagacity'. Dickens praised Charley Field's 'horrible sharpness . . . knowledge and sagacity'. A detective story by Waters alluded to the hero's 'vulpine sagacity'. The word then denoted intuition rather than wisdom. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries a 'sagacious' beast had a keen sense of smell: the early detectives were being compared, in their quickness and sharpness, to wolves and dogs.

Charlotte Bronte described a detective as a 'sleuthhound', a dog that followed the scent of its quarry's 'sleuth' or trail.* In Waters' stories of the 1850s, the hero was an amalgam of huntsman and hound, closing on his prey: 'the chase was hot after him', 'I ran him to earth', 'I was upon the right track'. 'If any profession now-a-days can be enlivened by adventure,' wrote the celebrated Edinburgh detective James McLevy, 'it is that of a detective officer. With the enthusiasm of the sportsman, whose aim is merely to run down and destroy often innocent animals, he is impelled by the superior motive of benefiting mankind, by ridding society of pests.' Urban detectives hunted their prey through the city streets, deduced the identities of burglars and fraudsters by their signs and signatures, their unintended trails and traces. London was 'a vast Wood or Forest', wrote Henry Fielding a century earlier, 'in which a Thief may harbour with as great Security, as wild Beasts do in the Desarts of Africa or Arabia. For by wandering from one Part to another, and often shifting his quarters, he may almost avoid the Possibility of being discovered.' As Victorian explorers spanned out across the empire, charting new lands, the detectives moved inwards to the core of the cities, neighbourhoods that to the middle classes were as strange as Arabia. The detectives learnt to distinguish the different schools of prostitute, of pickpocket, of shoplifter and burglar, and to track them to their lairs.

Whicher was a specialist in the city's shape-shifters. Like the heroine of Andrew Forrester's The Female Detective , he 'had been much mixed up with people who wore masks'. In 1847, for instance, he caught Richard Martin, alias Aubrey, alias Beaufort Cooper, alias Captain Conyngham, who took delivery of orders of fancy shirts by impersonating a gentleman; and the next year he captured Frederick Herbert, a young man of 'fashionable exterior' who had conned a London saddler out of a gun case, an artist out of two enamel paintings, and an ornithologist out of eighteen hummingbird skins. Whicher's fictional double was Jack Hawk-shaw, the detective in Tom Taylor's play The Ticket-of-Leave Man (1863), whose surname suggests a sure-sighted bird of prey. Hawkshaw is 'the 'cutest [acutest] detective on the force'. He pursues a master criminal who 'has as many outsides as he has aliases'. 'You may identify him for a felon today, and pull your hat off to him for a parson tomorrow,' says Hawkshaw. 'But I'll hunt him out of all his skins.'

Some of the local newspapers welcomed Whicher's presence in Wiltshire. 'The skill of a London detective, accustomed to the darker criminal atmosphere of a city, has been called in aid of our own able officers,' reported the Bath Chronicle that Wednesday. 'We cannot but believe the searchers are on the track.' Yet the crime in this pretty village took Whicher into murkier territory than he ever encountered in the city: this was not an investigation into aliases and false addresses, but into hidden fantasies, buried desires, secret selves.

CHAPTER EIGHT

ALL TIGHT SHUT UP

19 July

On Thursday, 19 July, Whicher arranged for the waters of the Frome to be lowered so that the river could be dragged. The Frome lay at the edge of the Kents' grounds, down a steep bank and under a thick, feathery arch of trees. After almost three dry weeks, the river was not as swollen as it had been at the start of the month, but it was still full and restless. To lower its level, men blocked off the rush of water from the weir upstream, and then pushed out in their boats, scraping rakes or grappling hooks along the riverbed in the hope of pulling up a discarded weapon or garment.

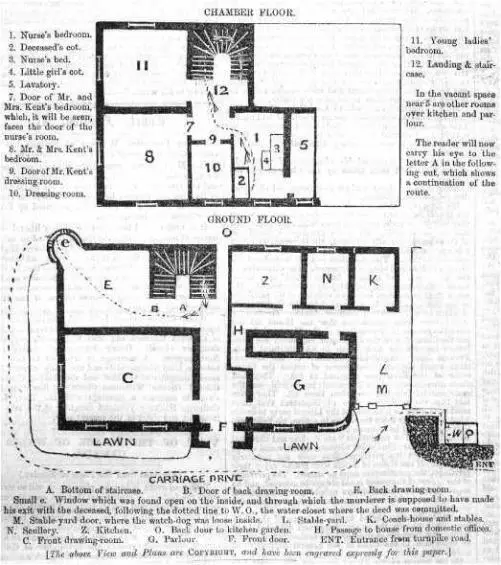

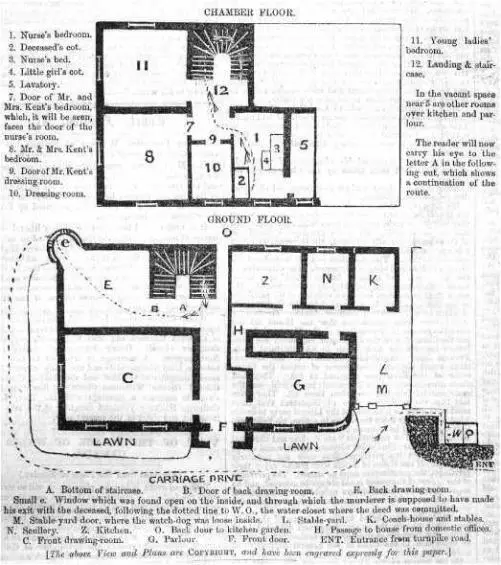

The police rooted in the flowerbeds and gardens around the house. They combed the field beyond the lawns. Samuel Kent described the grounds behind his property: 'At the back of the house is a large garden, and a field in which was standing grass; that field is about seven acres in extent . . . The place is much exposed; the premises are large and very accessible.' His description of a home that was helplessly open, as if backing onto a plain, captured his feeling of defencelessness after Saville's death. The family's privacy was destroyed, its secrets uncovered, the house and grounds and the lives of everyone within exposed to all.

At first Samuel did his best to point the police away from the rooms of his family and servants. Like Elizabeth Gough, he insisted that a stranger had killed Saville. Perhaps the murderer was a disgruntled former servant, he suggested, taking revenge on the family. Before Whicher's arrival, Samuel showed Superintendent Wolfe the places in which an intruder could have hidden. 'Here is a room which is not often occupied,' he said, indicating a furnished spare room. Wolfe pointed out that a stranger could not have known that the room was rarely entered. Kent took him to a lumber room in which toys were stored. No one would hide here, Wolfe said, because they would have feared someone coming in to fetch a toy. As for the cockloft beneath the roof, said Wolfe, 'There was a considerable quantity of dust . . . and I think that if a person had been there I must have seen traces.'

A few newspapers speculated that a stranger had committed the crime. 'A intimate personal knowledge of every room in Road Hill House . . . convinces us that it would have been perfectly possible not only for one but for half-a-dozen persons to have been secreted on the premises, without risk of detection, on that night,' reported the Somerset and Wilts Journal later , in an astonishingly detailed exposure of the building's private places:

Читать дальше