Nor are you at the factory.

You’ve handed in your notice, and you’re on the road.

It’s not clear from Mom’s letter where you are or where you’re going, only that it has all happened very fast and things are still rather vague, and that you will explain more yourself, in your next letter.

Nor is it clear from the letter that only a day has passed since you left the factory.

“Left on 4 Nov. 1959 at his own request,” says the official testimonial from the personnel department at the factory where you worked for twelve years.

“Final hourly wage rate: 294 öre. Conduct: Creditable. Working capability: Excellent.”

For a day now, you’ve been in untrodden forest.

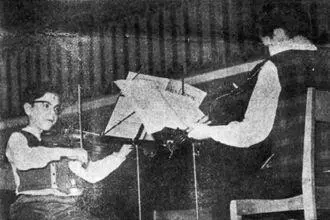

The local paper on December 16, 1959, runs a picture on the front page with the caption: “Göran Rosenberg and Paul Överström played Campra’s ‘Minuet’ in fine accord.”

I can’t remember your being there.

What became of the duet by Pleyel?

In the local paper on January 24, 1959, a thought for the day as usual. On this particular day, a thought about the Jews. In the story of the Good Samaritan in St. Luke’s Gospel, Jesus wanted to show “how wrong the Jews were in their hatred” and how “unprecedented it must have been for a Jew to listen to Jesus” and how Jesus “does what no other Jew would have done,” namely follow the commandment of love and not that of self-love.

Much later, I find out that you’re involved in a violent argument at the factory. It happens in the changing room, where you try to throw a punch at someone and this someone slams you against a locker so hard you end up with a concussion. This someone had wondered out loud what a person like you was doing among the ordinary workers. Why someone like you was not busy lending money or living off other people. Said he’d never seen a Jew working.

After the argument in the changing room, your headaches come more often. The headaches and the nightmares. Early one morning in May, I hear you calling unfamiliar names in your sleep. I don’t remember the names, but your voice frightens me. It’s not your usual voice. It’s a child’s voice, wailing helplessly through the wall between the living room and the bedroom where you both sleep. It’s already light outside and I lie awake waiting for the day to begin, because it’s the day the king’s coming to visit the truck factory and all the children of Södertälje have been given time off school to wave flags along the motorcade route, and I associate the sound of your voice calling out with the day I didn’t get to see the king.

On Thursday May 23, 1957, the king of Sweden and the queen of the Netherlands visit Södertälje. It’s a glorious late spring day, and just in the driveway down to the truck factory’s main offices the local paper counts thousands of children, all waving flags presented to them by Scania-Vabis as the king and queen drive past in a black Daimler and get out onto a red carpet to sit on a royal blue platform, and the reception committee bows and curtseys, and the entire program runs “immaculately.”

You stay at home that day.

I also stay at home that day.

Are we both ill?

I can’t reconcile the voice in the night with your lighthearted playfulness. You’re generally cheerful and jolly, pulling faces to make me laugh, yodeling with your hands cupped around your mouth, tapping out rhythms on your teeth with a pencil, giving silly names to things that have no name. Kigelmigel is your name for a fruit salad of oranges, apples, and bananas, topped with whipped cream. Kigelmigel sounds the way it tastes: soft, smooth, and sweet. Your invented names are all soft and rounded, with an — l or a — le at the end. Maybe it’s the affectionate Yiddish diminutives stepping in to soften the harsh language of Strindberg. I can hear them in the voice calling in the night, too. Mamale. Tattale .

Nor can I reconcile your restless activities and irrepressible ambitions with your frailty and fatigue, and with the recurring visits to the doctor. As I attempt, much later, to piece together all the activities you set in motion and all the projects you’re planning, they can’t all be fitted into the calendar; they trip over each other, overlap, squeeze each other out, as if not even the smallest chink of idle time is allowed to open up. Yet by 1947 you’re already consulting Dr. Paul Lindner at 26 Jungfrugatan in Stockholm about your headaches, anxiety, insomnia, and paranoid thoughts. From then on you go to see Dr. Lindner twice a year for a checkup and prescriptions for vitamins and sleeping pills. In 1950 your anxiety worsens for a time, and Dr. Lindner prescribes a powerful tranquilizer, Oxicon. The anxiety deepens into “particularly severe depression” over the course of 1959, and in a report dated March 3, 1960, Dr. Lindner proposes referring you for special psychiatric care.

Ambition and anxiety competing fiercely with each other, year after year, and I don’t see it. You don’t let me see it. You don’t let anyone see it.

You’re always so cheerful, Karin writes.

It’s only much later that I see the shadows dogging your every step, threatening to plunge you into darkness if you drop the pace even slightly.

It’s only much later that I’m able to reconcile the voice in the night with the voice that so lightheartedly and playfully gives softly resonant names to components of my world.

Time to say something about the term “survivor” as applied to people in your situation, the term that slowly crystalizes out as all others are tested and found inadequate, making the central element of your situation the fact that you’re still alive. People survive things all the time, of course, war, persecution, accidents, epidemics, without necessarily being termed survivors except with specific reference to the event they’ve survived, and mainly as a mere statement of fact. People who survive go on living, they don’t go on surviving. Surviving is normally not a continuous state but a momentary one. I think the term “survivor” initially has the same significance — a statement of fact — for people in your situation too. You’ve survived against all odds and must now go on living in one of the categories available to you: refugees, transit migrants, repatriandi , displaced persons, Polish Jews, stateless individuals. Initially it’s also clear to the world what exactly it is that you’ve survived and how implausible it is that you’re still alive. At least there’s no shortage of evidence. Or of pictures, for those who can bear to look at them. The words are still unfamiliar and unreal, and are sometimes prey to the confusion of languages — gas chambers, death factories, extermination policy, final solution, annihilation — but those of you who have survived have no reason to doubt that the world knows what you’ve survived, and that the world is shaken to its very foundations by the knowledge, and that the world afterward is no longer the same as the world before. It’s impossible to think anything else. It’s impossible to think you’ve all survived in order for the world to forget what it’s just been through and to go on as if nothing has happened. There must be some point to the fact that you’ve survived, since the main point of the event you’ve survived was that none of you were supposed to survive, that you were all supposed to be annihilated without a trace, without leaving even a splinter of bone behind, still less a name on a death list or a death certificate. So initially you all survive with the assurance that you are the traces that weren’t supposed to exist, and that this is your survival’s particular point. It may seem superfluous to attribute a particular point to your survival, as there is generally more point in being alive than in being dead, but how else to justify the fact that you’re alive whereas so many others are not? You all know, if anybody does, that your survival is a result of the most unlikely of circumstances and the most arbitrary of chances, and that by every realistic calculation of probability you should be as utterly annihilated as all those whose faces and voices continue to follow and haunt all of you. You may actually feel that you need to atone for being alive when they aren’t, particularly as I suspect that none of you can free yourselves from the thought that some of them deserved to survive more than you did. It’s a crazy thought, of course, since death and survival in Auschwitz depended not on merit but on the annihilation capacity of the gas chambers and crematoriums; however, I can appreciate that survival in such circumstances might seem unfair, or at any rate undeserved. Why me and not the others? Naturally it’s also an unbearable thought, which has to be pushed aside sooner or later if surviving is to turn into living. So I think it’s initially pushed aside by the assurance that you haven’t survived for yourselves only but for the others, too; that you’re the traces that must not be eradicated, and that you therefore owe a particular duty to the life you’ve been granted, against all the odds and beyond any notion of fairness, and that through this life you must justify the fact that you’re alive while the others are dead.

Читать дальше