Maybe someone shows you the picture — someone who already knows who you are and where you’ve come from.

But there I go, anticipating your life.

It’s so easy to do, and so unnecessary.

Time enough for that.

The place is still Alingsås, the time is the summer of 1946, and you’re still waiting for an answer that’s tarrying, and in the land of the vast forests there’s a debate going on about what to do with people like you. It can no longer be assumed that people like you can move on. That much has become obvious.

But it can’t be assumed that you can stay, either. In the land of the vast forests, the inhabitants aren’t used to the idea of thousands of people with wildly foreign languages and cultures suddenly taking up residence behind the Co-op at the forest edge. Only recently, even a dozen was unthinkable; jobs would be stolen, cultures destroyed, and the pure Swedish breed contaminated. Such views have not vanished completely, even if a deepening blush of shame now attends them. It may seem astonishing that such views persist at all, given that the land of the vast forests is crying out for people to man its unscathed cotton mills and truck factories. But xenophobia is old and ingrained, while the hunger for labor is new. On September 15, 1945, an editorial in the Dagens Nyheter sounds a note of warning about letting “the Polish-Jewish refugees” stay on:

If they hear that Sweden feels obliged to let them stay permanently, they will presumably be more than delighted. But the social workers who counsel them must beware of fostering that idea. It does not chime in with the authorities’ intentions, nor does it harmonize with opinion in informed Swedish Jewish circles. On the contrary, those circles urge caution in equating these herds [italics added] with the stateless group of the prewar years. They are concerned that the former will be indiscriminately let loose on the labor market. They also maintain that there should be careful checks on their conduct and a critical assessment of their professed demands.

Clarifying the position and future prospects of these groups is a matter of urgency. No doubt it will at least prove necessary to introduce a reasonable waiting time with provisional solutions, a waiting time that may well prove quite difficult. We are not used to dealing with people so alien to Swedish attitudes and standards. The feat of humanitarian rescue is worthy of honor. The rescue work that still remains may prove harder, above all because it must seek to extract the individuals from the mass.

Does it surprise you that such things are written? Or does it merely confirm what you already know or suspect about the land of the vast forests? I’m trying to understand why, over time, so many of you want to leave again, not because you’re forced to but because you want to, in fact long to, and reading lines like these helps me understand a little better.

Strangely enough, there’s some uncertainty about how many of you ultimately stay on. The Swedish historian Svante Hansson, who in 2004 published the most thorough investigation of the matter so far, concludes that it must be investigated still further, since you’re such a difficult group to keep track of. From his own findings, he estimates that in 1951 at least five thousand Jewish survivors still remain in Sweden, although the true total is probably considerably higher because no one knows exactly how many of the survivors marry Swedish citizens and thereby disappear early on from the register of stateless persons. He notes that Jewish survivors continue to leave Sweden for many years. By 1955, only 3,600 of the 1945 survivors are estimated to remain. Between 1945 and 1955, a total of 8,782 persons continue their journey with support from the Jewish community in Sweden. In 1946, there are few countries to which they can go, Palestine and the United States being all but closed to Jewish immigration, South America far away and complicated, Australia far away and expensive, Europe as closed as before the war.

In the beginning nearly all of you want to move on, but as answers fail to arrive and onward journeys have to be postponed, the land of the vast forests and labor-hungry factories takes hold of you, one by one. A temporary stay has to be extended for an indefinite period, and in an indefinite period there are many decisions that must be made and many things that must happen without anyone’s really having made a decision about them.

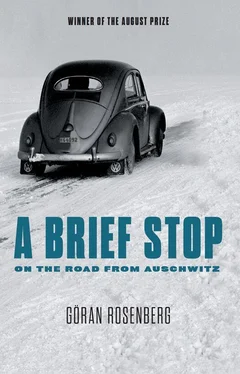

In the end, a decision must be made as to whether Sweden is to be the last stop on the road from Auschwitz and the place to start life anew.

In the early years, it’s the labor hunger that decides where a new life can make its beginnings. These are the years when Sweden is transformed from a country convinced it can’t tolerate too many “aliens” to a country crying out for them. By 1948, a hundred thousand “aliens” have been granted Swedish residence permits, of whom “almost all are fully employed in the labor market.” This last part is carefully recorded on July 31, 1948, on the front page of my newspaper of record throughout this narrative, Stockholms Läns och Södertälje Tidning , and immediately clarified with “no one granted a residence permit here has the right just to drift aimlessly.” The director of the State Aliens Commission, Nils Hagelin, is also keen to clarify: “Work is the best medicine for those who come from war-torn countries and find it hard to cope with orderly conditions.… That is how they will most rapidly become part of society, and there are very few who abuse our hospitality by making trouble.”

I don’t know what Mr. Hagelin means by making trouble. I only know that in a police report submitted to the Ministry of Justice in Stockholm on March 12, 1954, in connection with your application for Swedish citizenship, personnel manager Stina Fors at Alingsås Bomullsväfveri AB has something to say about making trouble.

Yes, I know, that’s much later, and again I’m anticipating events, but this concerns your time in Alingsås — though goodness knows how Miss Fors after so many years can remember this specific thing about you. Anyway, here the word “trouble” appears in connection with your name, which is the reason I mention it, because it might tell you something about what at this time was meant by trouble in reference to people like you.

So that there may be no misunderstanding, let me point out that Miss Fors is the only person in the police report from Alingsås to associate you with trouble, in fact the only one to have anything remotely unfavorable to say about you and the woman who is to be my mother and who is applying for Swedish citizenship together with you. The owner of the Pension Friden, Evald Stenberg, remembers “Mr. and Mrs. Rozenberg” as “very reliable, steady and decent, and he can therefore recommend them for Swedish citizenship.” The waitress at Pension Friden, Margareta Åberg, remembers you both as “decent and steady” and recommends the same. Only Miss Stina Fors remembers differently:

Dawid Rozenberg was employed as a weaver at the factory in the period 4/2 1946 — 2/8 1947 and from 19 October 1946 until the time he left, he rented lodgings in the factory-owned property at 29 Lendahlsgatan, where he lived with Hala Staw, who was at that time working at the linen factory.

He did his job satisfactorily and the factory did not have any particular complaints about him, but as a tenant he caused the company some difficulty in that he — or possibly Staw — often made trouble with the other tenants.

Miss Fors is of the view that if Mr. and Mrs. Rozenberg are still behaving as they did during their time in Alingsås, it is questionable whether they should be granted Swedish citizenship.

Thus has the woman who is to be my mother, Hala Staw, or Haluś as you usually address her in your letters, or sometimes Halinka, almost imperceptibly joined the guests at the Pension Friden in Alingsås and taken a job as a seamstress at the linen factory, Sveriges Förenade Linnefabriker, and on October 19, 1946, moved with you into a temporary, factory-owned accommodation for foreign textile workers at 29 Lendahlsgatan, where you and she are now referred to as “Mr. and Mrs. Rozenberg,” so perhaps it would be appropriate to explain how this has come about.

Читать дальше