In this flat, the Child takes up more space than the naked eye can see. Around the Child, an expanding web of ambitions and plans. The little cardboard box of alphabet blocks, made and decorated by hand, is not just a Toy but also a Project, and the perpetually changing letter combinations that the Child and the young man who is now his father lay out on the living room floor on those long Sunday afternoons form not only the words of a new language but also the building blocks of a new world. The Child shall make the Place his own so that a new world will become possible for them as well is the Project that rapidly fills the small apartment with its invisible inventories of dreams and expectations. After all, what the two new arrivals need is not a roof over their heads but firm ground beneath their feet, and if the child can take root somewhere, perhaps they too, in time, will find a foothold.

The Child, then, is me. And the Place I will make theirs by making it mine has its geographic center in a yellow three-story apartment block with two entrances and eighteen rental units just below Platform 1 of the railroad station, where the big passenger trains make a brief stop on their way south, even the expresses, even the night trains, even the trains to Copenhagen and Hamburg. From the kitchen and living room windows in the small first-floor apartment in the block nearest the forest, you can see people moving about in the railroad cars. And people being moved along by the railroad cars. And with every train, behind the reflections in the railroad car windows, a new world, mutely oblivious of its brief stop in the world that is to be mine.

Foreign kings are also said to have made a brief stop here, to be greeted by flag-waving people on the platform or to have their royal railroad cars routed into a siding for a royal breakfast and then coupled to the Swedish royal train in order to arrive in full state at Stockholm Central and the Royal Palace, but I have no memory of such a world outside our kitchen window. Presumably it was before the war, before our block was built, and before I existed, when the only things to be seen if one happened to look out of the railroad car window in our direction were sandy heath and sparse pine forest.

What’s certain is that a few months after the end of the war, General Patton, who first won fame as an armored division commander, made a brief stop on Platform 1 before boarding the 21:53 train to Malmö. Earlier that day he’d visited the Södermanland tank regiment at Strängnäs and studied the twenty-two-ton Swedish tank model 42 and the Swedish armored troop carrier SKP, built by Scania-Vabis, and he’d declared the Swedish carrier to be superior to the corresponding American model. Though perhaps he was just being polite. And perhaps not at the moment seeing entirely eye to eye with the American military leadership, which had just relieved him of his command of the Third Army. It was the evening of December 3, 1945, and a large crowd had gathered at the station to pay tribute to “the popular general.” As Patton’s train pulled away from the platform on the southbound track, loud cheers were heard. That too was before I existed, but by then our apartment block was already in its ringside seat, newly built and filled with tenants, and perhaps some of those who had just moved in had been tempted on that late December evening into opening one of their windows facing the platform to see if they could catch a glimpse of the man who only a year before had crushed German resistance in northern France with a sensational combination of genius and brutality. George S. Patton was his full name. I remember him only as George C. Scott in Patton and might therefore have been inclined to cheer less lustily, but those who with no reservations whatsoever shouted hurrahs for the real Patton on the platform outside our future kitchen window and saw him in the flesh as he climbed aboard the train to Malmö, and who maybe still felt the anxiety of wartime in their bodies, would surely never forget what they had seen, since they turned out to be among the last people to see General George S. Patton alive. Just a few days later, he was fatally injured in a car crash outside Mannheim in defeated, occupied Germany.

My first proper memory of the station outside the kitchen window is of trains that never stop as they clatter endlessly through the nights — caravans of freight cars, open or covered, screeching and whining like an overburdened chain gang on a punishment march. I remember them because they’re the first things to wake me as the windowpanes rattle and the rail joints hammer against the wheels and the crackling flashes from the double locomotives cut through the curtains and a putrid smell of chemicals and decay rolls down from the platforms and into our beds and our dreams.

On the narrow strip of ground between the apartment blocks and the steep slope up to the fence and the platforms, the architects of the Place have left some of the original pines standing and encouraged grass and white clover to spread beneath them. It’s my first playground. I hunt for four-leafed clover in the grass, play hide-and-seek among the trees, and float bits of bark in the puddles on the footpath below the embankment. A four-leafed clover is an early sign of luck, a double four-leafed clover an early mystery. Gradually the games grow bolder and more absorbing and go on later and later into the afternoon and can’t be immediately interrupted just because somebody opens the kitchen window and shouts that it’s time to come home: Chodź do domu , calls the voice from my kitchen window. The person calling is the young woman who’s now my mother, and she’s calling in the first language I learn and the first language I forget. In winter the largest stretch of grass between the pines is hosed with water, and the bigger boys come down with their ice hockey sticks and the games grow rougher and it gets dark earlier and the voice at the window takes on a more anxious tone. And soon, another language.

They want to leave nothing to chance. Nothing is to come between the Child and the Place. No foreign words. No foreign names. Nothing that might make the Child lose the foothold for all of them. So when they hear that the Child’s first words are in a foreign language, they force themselves to speak to him in a language still alien to them, and they’re quick to put books in the new language into his hands and to spell out the words of the new language for him in alphabet blocks on the living room floor.

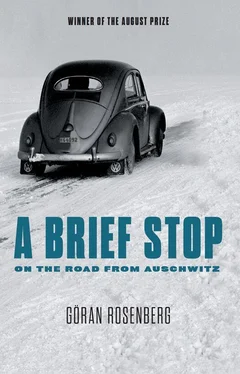

On the advice of new friends, they’ve already fixed on a name for the Child. It’s the most common boy’s name in the new language. The name is important, their friends have told them. A foreign name stands out and becomes a handicap. The name they initially chose, Gershon, after the Child’s paternal grandfather, is therefore superseded by Göran, a name that seems devised to distinguish between foreigners and natives. The complicated intonation of the long ö is what does it. They could also call him Jakob, after his maternal grandfather, which would be easier to pronounce and wouldn’t really stand out because it’s a name that belongs here too, but I imagine they want to play it safe in the name game. They give him the name Jakob as well, but a middle name isn’t something you shout out of a kitchen window.

In the matter of the Language, they’ve calculated correctly. Perhaps in the matter of the Name too, but that’s harder to know for sure. It’s safe to say that the Language is what first binds the Child to the Place, since it’s here that the Child sees everything for the first time, absolutely everything , without the weary discernment that comes with knowledge of what everything in the world is supposed to be called and experience of how everything in the world is supposed to look.

Читать дальше