On 19 June Gaddafi announced a bounty for any NATO aircraft shot down. For 32 Brigade an Apache was their most likely prize. We were well and truly in the frame for a massed ambush somewhere near Zlitan. On 21 June a new US Navy remotely piloted helicopter drone, known as Fire Scout, crashed near Zlitan. Libyan State TV showed images of wrecked helicopter parts and jubilant pro-Gad demonstrators claiming to have shot down an Apache. The hourglass had turned; we needed luck as well as judgement to bring us safely though the campaign.

Chapter 8

The Raid on Brega

With the bounty promised to anyone who shot down a helicopter, surface-to-air missiles and anything else that could hit us were now massing on the coast and the risk-versus-reward calculation was changing. We didn’t notice. The two SA-24 shoots had scared us, but our defensive equipment and our tactics had worked. This made us braver. They had thrown their best at us and we had killed them in reply. In fact, we had, unwittingly, normalized the threat. Right from the first mission, getting brassed up by big weapons was just what happened. The Apache was designed to deal with this, and we were happy to be there, but unfortunately we were being hampered by the risk aversion of our operational heritage. When the missiles started coming at us it was a matter of duty and common sense to stand and fight and kill. Taking on the most lethal of Gaddafi’s weapons was expected with each mission. The bounty, the change in their MO and the warnings made no difference. The rapid immersion in violence had changed us. I had lost my understanding of what normal was. Launching every mission with a high chance of dying had replaced normal.

After the high octane SA-24 rampage of Zlitan the worry-beads in Italy wanted to move us away from that area. It was all quite sensible. An increased threat from a weapon system that would surely bring us down, a bounty on our demise and an enemy determined to see us die were all big concerns. We had to come up with new ways of keeping Gaddafi guessing. Nick Stevens and I scoped all sorts of options, including feet-wet day raids and long periods on alert on deck ready to react to any opportunity target. None were taken. We just needed to take the heat out of the threat, and that meant moving away. Twenty days after the first mission we returned to Brega.

An elite battalion from 32 Brigade had moved from Zlitan to reinforce the town, which was now completely militarized. ‘Elite’ in pro-Gad terms meant SA-24, triple-A, superior training and absolute loyalty to the regime. A new location, yes, but the same pro-Gad would be firing at us. The risk was unchanged, but we didn’t care. We knew we were good for the fight. Zlitan, Brega or Tripoli, we were good to go wherever the targets were. In terms of combat psychology we were still excited and willing to take risks. It was exhilarating, and continually getting away with our lives had reinforced our collective courage. Rushing in low-level against more of the same was welcomed. We relished it.

The raid on Brega

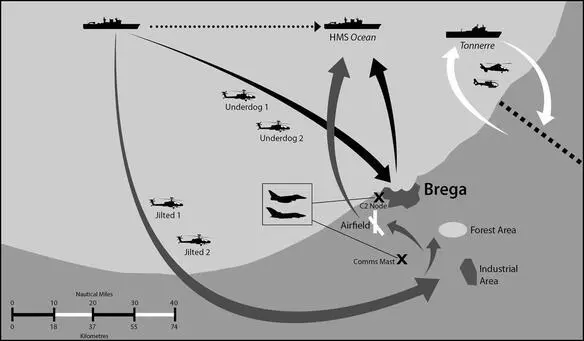

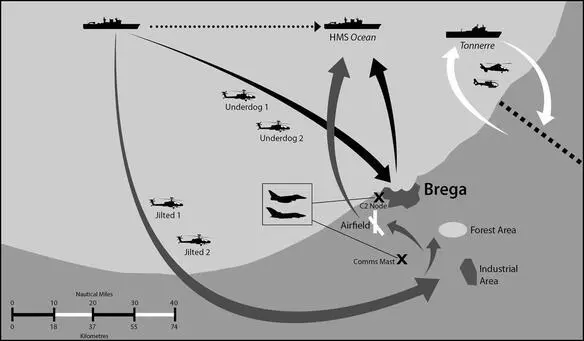

I flew to the French amphibious vessel, Tonnerre , to discuss their experiences of Brega and share ours of Zlitan. They had been operating close to the front line and flying several patrols night after night to the same target area with tremendous success. They were a big outfit, too, with a large planning staff dedicated to aviation as well as a squadron twice the size of ours. We had an open, brotherly discussion about the threat, the firing points, the pro-Gad MO and what to do about it. They had certainly shaken Brega and given the regime serious concerns. They had battered the enemy relentlessly for three weeks. Now we were going to join them in a combined raid to strike pro-Gad positions throughout Brega.

When the outline mission pack came in I called Chris James at the CAOC who explained the plan:

It’s probably a four-aircraft job. The jets will drop a C2 node in a warehouse and a communications mast just west of the town at H hour. That’s the important event – everything hinges on it. You need to be getting into position before that. The French will be going in at the same time right up by the front line. That’s east by a few kilometres so you’ll be over Libya at the same time but we have agreed a deconfliction line to stop you bumping into each other. As soon as the jet strike goes in you are clear to proceed. If you need to change the timings you’ll have to do it early because these guys have some seriously complicated refuelling schedules to coordinate and we need to tell the French. There are two areas for you to strike. The first is close to an industrial complex south of the town, an area where they are routinely hiding technicals; and the airport might have some action going on too. The other area is the port itself. It is teeming with pro-Gad and technicals.

‘Sounds like at least a four-aircraft job,’ I replied, hopefully.

‘Yes. The French have been hitting them hard since the start of the month, since that first night of the op. That’s probably why they’ve moved in this battalion from 32 Brigade. You know what this means. It’s likely to be strong out there… they’ll have a real go at you.’

We knew it. Pro-Gad would be pleased with his Fire Scout shoot-down. They would believe the regime propaganda that it was an Apache. And they would be bold about taking us on. Lots of them, with triple-A and SA-24. A proper shoot-down would be a big boost for the regime. Conversely, a massive kicking from four Apaches would do away with their confidence and wreck morale.

‘Okay. We’ll be on our guard and ready for it. Surprise and firepower will shape the plan. Anything else?’

‘There are reports of an SA-6 about twenty miles to the south. We don’t know if it is just the radar or if it has missiles too. It occasionally gets turned on and then quickly goes off, before the jets get a chance to strike it. You’ll have to treat it as hostile if you get a tag.’

An SA-6. This was new. After the phone call was done I flicked back through my notebook and saw that I’d written ‘SA-6?’ back in May, along with ‘SA-24 probably’ and ‘SA-everything shoulder launched probably’. I called across the flip-flop to Charlie Tollbrooke, ‘Charlie, SA-6, refresh me would you old boy.’ The hum of industry in the flip-flop instantly ceased. All the aircrew stopped their planning and looked at me and then at Charlie.

Charlie had the facts in his head right away: ‘SA-6. Okay, SA-6. Well, known as “Gainful”. It has a radar mounted on a vehicle and the missiles are on separate vehicles, so the missiles and the radar are always separate and difficult to find. It is a particularly deadly helicopter hunter and very simple.’

Simple technology means cheap to build, which in turn means mass-produced. Mass-produced Soviet technology today means available to any state with a little spare change. Libya, as it happened, had a lot of cash.

With nine aircrew listening, Charlie continued, ‘The system usually has four missile vehicles carrying three missiles each. The radar is called “Straight Flush” and it has a load of radar and optical sensors that find and track the target. If it is on and we are in range, it will find us. Once the radar people are tracking a target they hand it over to the missile people. The missile people then press the go button and a missile or missiles go for the target.’

He paused. ‘Are we expecting SA-6 on the next mission?’ he asked.

All eyes on me now.

I looked at the team, then at my notebook, then back at Charlie. ‘In the south, yes. And since Staff Blackwell and I are going to the south and you and Mr Hall are coming with us, then very yes. Yes we are.’

Читать дальше