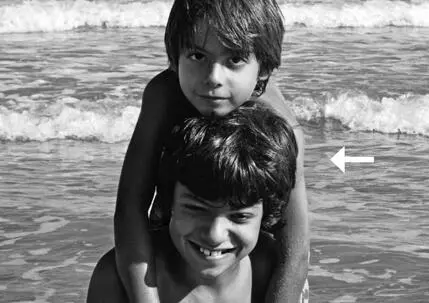

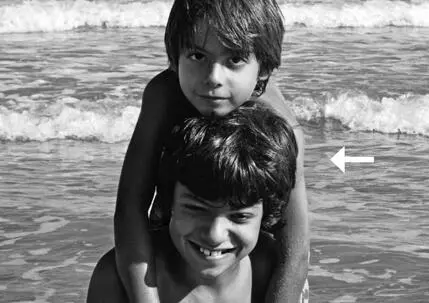

Tito and Nico: one is sewn to the other.

121

122

In the previous image: my Siamese twins.

123

Tito improved rapidly at Padua Hospital.

On the second day of his life, he stopped having convulsions.

On the third day of his life, he could breathe without the help of machines.

On the fourth day of his life, he uttered a sound that the doctors interpreted as crying. On the fifth day of his life, he opened his eyes wide. On the sixth day of life, he took milk from the breast. On the seventh day of life, he was discharged from the neonatal intensive-care unit and placed in a room with my wife.

124

A week later, Tito came home.

125

We lived in the Palazzo Barbaro Wolkoff on the Grand Canal, next to the Palazzo Dario.

Who designed the Palazzo Dario?

That’s right: Pietro Lombardo.

126

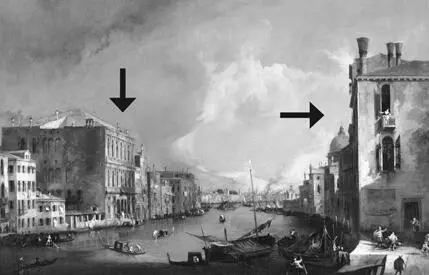

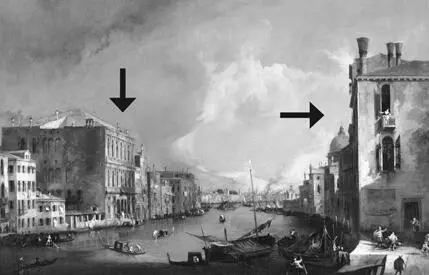

(Picture Credit 1.9)

127

In the previous image: the Palazzo Barbaro Wolkoff, where we lived, and to its right the Palazzo Dario.

The painting is by Claude Monet. It dates from 1908.

I am at the window, cradling Tito and looking out over the Grand Canal.

128

Claude Monet stayed in Venice two and a half months.

When he painted my windows, his wife, Alice, wrote in a letter to her daughter Germaine:

He’s doing some marvellous work and, between you and me, it’s a welcome change from those old water lilies .

129

I am the Claude Monet of cerebral palsy. Tito is my water lily. He has become my sole subject matter. I devote myself entirely to him, he is my one passion. I never tire of my subject matter either. I always find in him an unexpected color, an unexplored shadow. Tito is the Absolute. Tito is Everything.

130

Pietro Lombardo designed the Palazzo Dario in 1486.

In the same year, Jacopo Sansovino was born.

Like Pietro Lombardo, Jacopo Sansovino is linked in circular fashion to Tito’s birth. First, he designed one wing of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, completing Pietro Lombardo’s work. Then he designed the Church of San Giuliano, adorning its doorway with a statue of Tommaso Rangone. Finally, he designed the Palazzo Corner, opposite the Palazzo Dario and the Palazzo Barbaro Wolkoff, on the other side of the Grand Canal.

I could see the Palazzo Dario and the Palazzo Corner from my window.

131

(Picture Credit 1.10)

132

In the previous image: on the right, the Palazzo Dario, designed by Pietro Lombardo, and on the left the Palazzo Corner, designed by Jacopo Sansovino.

The painting is by Canaletto. It dates from 1738.

I am still at the same window, cradling Tito and looking out over the Grand Canal.

133

According to John Ruskin, the Palazzo Dario is an “exquisite example” of the domestic architecture of the time. The Palazzo Corner, on the other hand, built half a century later, in 1537, was “one of the worst and coldest buildings of the central Renaissance.”

The Palazzo Dario expressed the soul of a true artist like Pietro Lombardo, who could also reason, but only occasionally, and who could even acquire knowledge, but only the knowledge he could pick up “without stooping, or reach without pains.” The Palazzo Corner, on the other hand, expressed Jacopo Sansovino’s academic pride, along with his geometrical fanaticism, which could “be taught to any schoolboy in a week.”

The Palazzo Dario was “good for God’s worship.” The Palazzo Corner was “good for man’s worship.”

134

I never worshipped God. I never worshipped Man. However, I began to worship Tito. I began to worship domestic life. My gospel is an electricity bill. My temple is a greengrocer’s shop.

Tito is Everything. A tomato is Everything.

135

The Palazzo Dario and the Palazzo Corner have spent five hundred years debating the great themes of humanity, shouting their arguments to each other across the Grand Canal.

If the Palazzo Dario was Socrates, the Palazzo Corner was Meletus. If the Palazzo Dario was Dante Alighieri, the Palazzo Corner was Farinata degli Uberti. If the Palazzo Dario was Don Quixote, the Palazzo Corner was Sancho Panza. If the Palazzo Dario was Naphta, the Palazzo Corner was Settembrini. If the Palazzo Dario was Lou Costello, the Palazzo Corner was Bud Abbott.

Only Venice could give me this.

136

After designing the Palazzo Corner, Jacopo Sansovino was commissioned to design the reading room of the Biblioteca Marciana — St. Mark’s Library.

Pride of Science and Pride of State revealed themselves in his imposing vaulted ceiling in the Roman style.

In 1545, the ceiling collapsed.

That’s right: The Fall .

Jacopo Sansovino was arrested and ordered to rebuild the reading room in the Biblioteca Marciana at his own expense. Jacopo Sansovino was forced to replace the imposing Roman-style vaulted ceiling with a flat ceiling.

I am the flat ceiling of cerebral palsy.

137

I moved to Venice in 1987. I was twenty-four years old.

For me, the best thing about Venice was its regressive nature. For me, the best thing about Venice was its nonconformist reactionaryism.

Living there was like living in an Amish town. I saw Venice as an Amish town for intellectuals. Its lofty irrationality is in sharp contrast to the enlightened popularism of my time. Its splendidly anachronistic nature makes a mockery of any kind of haughty progressivism.

A child from an Amish village who had not been allowed to be vaccinated could die of measles. In Venice, as I discovered some years later, a child could die at birth.

138

When I moved to Venice, I was writing my first novel.

After writing my first novel, I wrote my second novel. After writing my second novel, I wrote my third novel. After writing my third novel, I wrote my fourth novel.

When Tito was born, I was writing my fifth novel.

That was how I saw my future: living in Venice and jumping from novel to novel.

Tito’s birth changed all that.

139

The first months of Tito’s life were just like any other baby’s.

He breastfed. He was taken for walks. He slept.

Every six weeks, we took him to the neurology department in Padua Hospital.

The doctors tested his reflexes and measured the size of his brain.

The results were always perfectly normal. The doctors assumed that Tito had escaped unharmed from his bungled birth.

140

141

In the previous image: a perfectly normal Tito.

142

Just before he was six months old, Tito went for another examination at Padua Hospital.

His neurologist lay him face down on the stretcher. At that moment, he should have rolled over onto his back. Instead, he merely waved his little arms about, but — like a turtle — he was unable to turn over.

Читать дальше