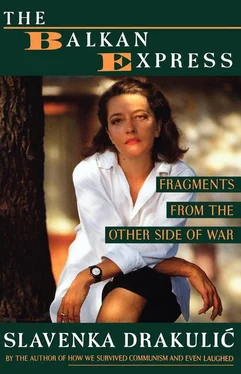

Slavenka Drakulić - The Balkan Express - Fragments from the Other Side of War

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Slavenka Drakulić - The Balkan Express - Fragments from the Other Side of War» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:New York

- ISBN:0-393-03496-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

— Do you still remember what the man looked like, his face?

— Yes…

— You remember the faces?

— Yes, you do… The next day we were keeping watch in a house near the tank route and we saw two soldiers coming. My friend took the sniper’s rifle, he wanted to kill them without making too much noise so we wouldn’t be noticed. But then he lowered the gun, he said these soldiers were young army draftees, not reservists. They were about fifty yards from us. They had white belts, they were their military police. When they got to about ten yards from us, we yelled at them to stop and drop their weapons, but they began firing at us. In fact, they fired at the house, they didn’t see us. One of them almost shot my brother, then my brother returned fire and shot him. The other one threw himself on the ground, we could only see his arm with the gun. My brother and another friend sneaked up to him with grenades, came to within two or three yards of him and when they saw he was wounded, he cried for help. They told him to give himself up and nothing would happen to him. Or they’d throw a grenade. When he gave himself up, we saw he was really just a kid.

— So he was a draftee and not a reservist?

— Yeah, a draftee from Nis. We felt sorry for him, he was born in 1972, like me…

— What happened to him then?

— We took him to the hospital, they bandaged him there and he was sent to Zagreb with the first convoy out of Vukovar. He could choose, he could go to Belgrade, if he wanted to. We talked to him, we took some juice to him because there was no juice in the hospital and finally we made friends with him. His name was Srdjan. He told us to bring him the red star from his cap and he’d eat it before our eyes! He had only now realized that they’d been made to go to war against Croatia and he wasn’t guilty, he said, because he didn’t volunteer, he was drafted. Within fifteen days only two out of his entire group of thirty-six had survived. The rest were killed. And all of them were born in 1972 or 1973, just like us…

— Did you look for him in Zagreb?

— I did, I thought he might be at the Rehabilitation Centre, but I didn’t find him. I only found a friend of our commander who had lost both legs.

— How did this happen?

— It was the day of the big battle on Trpinjska cesta. We couldn’t find our commander and the other fighters told us to look for him in the hospital. We asked the doctor where our commander was but the doctor said, I’m not going to tell you anything, go down to the basement and see for yourself. The commander was lying there and beside him was his brother, stroking his head. When we came closer, we saw that the commander’s left leg was blown in half, the lower half was missing, while his right leg was scorched completely and so was his right hand. We stayed with him for two hours without saying a single word, we just wept. He’s twenty-two. I think that’s when I felt worst.

— Why then?

— He was our commander not because someone appointed him but because we picked him to be our commander. He was a brave man, tall, six feet eight perhaps, and strong. He wasn’t afraid of anything. We looked up to him, all of us. And when I saw him lying there, without legs, crippled and totally helpless… I felt terrible.

— Did it perhaps occur to you to quit at that moment?

— No, it didn’t, once you’re inside you can’t get out, you can’t quit.

ZAGREB MARCH 199215

AND THE PRESIDENT IS DRINKING COFFEE ON JELACIC SQUARE

It was on Saturday 22 February at five minutes to one in the afternoon that I saw the new Croatian President Franjo Tudjman for the first time. I saw him through a huge, thick glass window of a very posh cafe on Duke Jelacic Square. The cafe was full of people squashed at French-type tables of fake marble. But I could not tell if they were mainly ordinary visitors or bodyguards, only two of whom – tall, good-looking boys – I could make out by the door and two others sitting at the table next to his. I also noticed a few old ladies looking at the President with adoration while eating their tarts and drinking espresso. The rest of the people in the cafe generally seemed to be pretending not to be excited, that he was nobody special or that they meet him at least twice a week in this same place – a Central European kind of custom. Dressed in a dark grey suit and a white shirt tied tightly with a dark blue tie, he sipped his coffee slowly: not Turkish coffee, I suppose, since that is what those barbarian Serbs usually drink while we Europeans drink espresso or capuccino or perhaps a ‘melange’. He looked relaxed and in a good mood, apparently amused by what a much younger man whom I recognized from TV as one of his advisers was telling him, leaning across the table to get closer to his ear. The President smiled, barely parting his lips: one more of his famous unpleasant smiles – he couldn’t do much about that, I guess – which gave his face the expression of a bird, an owl perhaps. When he lifted his head with a tiny white cup in his hand to look through the window to the square I could tell from the look that he didn’t really see either the window or the square behind it. His thoughts were far away, far beyond us all standing there, the kind of look that makes you feel like an extra in a Hollywood B-production, a super-spectacle about the war in the Balkans.

In front of the cafe window, surprisingly enough, there were not many people, only a few reporters who ran between this scene and a crowd of some several hundred people at the eastern-edge of the square, not more than thirty yards from the cafe. It was a protest meeting of people from Vukovar, civilians and fighters together, people who had lost their homes as their entire city of 50,000 inhabitants had been shelled to ruins in the previous months. They had called the meeting because they were not getting the kind of help from the government that had been promised, from payment to soldiers and wounded people, to apartments and financial help for relatives of the thousands of victims. The other thing that outraged them was the way a police had intimidated a man who, until three months ago, was the leader of defence of Vukovar, a war commander nicknamed Hawk, whom all the soldiers as well as the media acclaimed as a hero. Nonetheless he was arrested and when everything else failed, including a charge of treason, he had been accused of the theft of some 300,000 German marks in cash, collected by Croats living abroad in order to buy arms for Vukovar. Everyone knew that behind his arrest there was a much bigger political issue because Hawk had accused the Croatian army headquarters, the government and the President himself of deliberately withholding arms from Vukovar and of not giving permission to evacuate remaining civilians from the city before the Serbian army entered it. Hawk claimed that as a result some 4000 civilians had either been killed or disappeared. The police held him in prison for about a month where he was severely beaten and tortured, as he later told reporters. Then they let him go, but the investigation is still continuing.

I went across to join the meeting. I saw a group of people in front of TV cameras, standing under a cold drizzle. ‘Even the sky shows us no mercy,’ said a woman behind me. Hawk was just explaining to the surprised journalists that the police authorities had cut off power to the microphones even though they’d sought regular permission for the meeting days in advance, just as one had to do in the days of the communist regime. And in just the same way (what else could one expect when most of the key men in the police had remained to work for the new state?) they’d had their the electricity supply cut off at the last moment, permission or no permission. A tall, strong-looking man had informed the people waiting in the rain, but they decided to hold a meeting anyway. Another man, rather old and skinny, who I later heard was a famous doctor from the Vukovar underground hospital, climbed on an improvised ‘stage’ made of plastic boxes at the end of Jelacic Square, and started to talk to the people there, but his weak voice was carried away by the wind and the murmuring of the crowd. But the people gathered in the square didn’t sound angry; from their faces they looked as if they knew something like this was to be expected after everything else that had been done, or rather not done for them by this government and this city, where the days of the week still had a proper meaning, where people could still treat the Saturday family lunch as if it were the most important thing in the world.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.