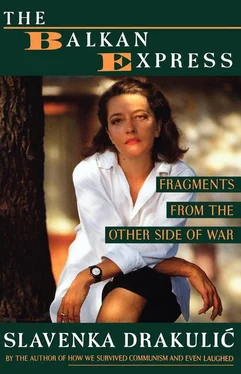

Slavenka Drakulić - The Balkan Express - Fragments from the Other Side of War

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Slavenka Drakulić - The Balkan Express - Fragments from the Other Side of War» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:New York

- ISBN:0-393-03496-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sitting across from my mother, in the place where he used to sit, for the first time I feel close to my father. It is only now that I can grasp the futility of his life, frittered away by history. Like a mirror, it reflects the entire period between the two wars, the last one and the present one, the time when people like him believed that communism was possible. In the mid-sixties he took off his uniform and went to work for a furniture retail company, but he remained a member of the Communist League, believing he owed that much to the party which had transformed the country and pulled it out of poverty and backwardness. Nevertheless, he used to turn off the TV set in the middle of the news programme even before Tito’s death in 1980. They’ve screwed it all up, he would say about his former comrades. His idealism was long gone, the country was falling apart and the communists were refusing to let go of power; that was obvious. Father sat over the spread-out papers and grew old, sinking together with the state he had helped build. He died in the middle of November, 1989, the month and the year that marked the beginning of the final collapse of the communist system. Thank goodness he died – said Mother a couple of months later – this would’ve been the end of him. For her family, she has been guilty of being his wife; for the communist state, she was guilty of being from another class; and now, when he is dead, she is guilty again. The guilt by relation she had been saddled with in distant 1947 is today still hers to carry. Yet, she cannot understand how her dead husband can possibly be the enemy of the new Croatian state. ‘Why did they take my pension away?’ she says. ‘What will I live on?’

Night falls. It is dark, I can no longer see her face, only the glowing tip of her cigarette. She does not turn on the light. She says it’s because of the war, the air-raids, but I know that she is in fact saving electricity. It seems to me Father is here, with us – the man whose past needs to be forgotten now. But he is not the only one: now the time has come to count the dead again, to punish and to rehabilitate. This is called ‘redressing the injustice of the former regime’. In the spring of 1990, the monument to the nineteenth-century Croat hero Duke Jelacic, removed by the communist government after World War II and relegated to what was known in the official lingo of the day as the ‘junkyard of the past’, has been returned to its original place; Republic Square has been renamed after him. The name of the Square of the Victims of Fascism, where once stood the notorious Ustashe prison, has also been changed. The names of virtually all major streets and squares in the cities throughout Croatia have been changed – even the names of cities themselves.

The symbols, the monuments, the names are being obliterated. For a while people will go on remembering the old names, there will be visible traces on the facades marking the spot where the old nameplate was. First the material evidence vanishes, then frail memory gives way. Thus altered and corrected, the past is in fact erased, annihilated. People live without the past, both collective and individual. This has been the prescribed way of life for the past forty-five years, when it was assumed that history began in 1941 with the War and the revolution. The new history of the state of Croatia also begins with war and revolution and with eradicating the memory of the forty-five years under communism. Obviously, this is what we have been used to. It is terrible that this is what we are supposed to get used to again. Even more terrible is that we ourselves tear down our own monuments, or watch it happen without a word, with heads bowed, until a ravaging, ‘correcting’ hand touches our own life. But then it is too late. In Croatia’s ‘new democracy’, will the past be officially banned again?

Finally, I tell Mother that changing Father’s tombstone is out of the question. Every small place has its own, now already official, redesigner of the past who acts in the name of the new historical justice. So far the graves have remained untouched: perhaps the graves will be the sole survivors from the previous system. But if someone indeed intends to remove the star from my father’s grave, let him do it by himself, she doesn’t have to help. ‘Don’t change his life, he doesn’t deserve it,’ I say. ‘If it must be, if our past must be blotted out, at least let others do it.’ Mother cries helplessly.

RIJEKA WINTER 1991/212

AN ACTRESS WHO LOST HER HOMELAND

Idon’t know how to begin the story about M, an actress who has lost her homeland in the war. While she sits in an armchair facing me, I cannot help but think how small she looks, smaller than when I saw her last. And quite different from when up on the screen. This is probably always the case with film stars: it is difficult to recognize them because in person they hardly look like the characters they play in the movies. I saw her in Zagreb a year ago at a premiere of a film: the war had not yet begun, people were celebrating the advent of the new government, the streets were clean, the freshly-painted facades shone in their pretty colours, new shops were being opened, the future looked like a birthday cake with whipped cream and pink sugary icing. M was glowing, people thronged around her and kissed her on the cheeks. She was laughing. She looked happy. That night in the Balkan Cinema foyer, everybody was her friend. And then…

The attacks on M began when it came to the attention of the press that she had given a brief, ten-line statement in the bulletin of Bitef , Belgrade’s international theatre festival. The theatres from Croatia had boycotted the festival held in Belgrade which in the meantime had ceased to be the capital of the joint state of Yugoslavia and instead become the capital of the enemy state, Serbia. M was the only actress from Zagreb performing at the festival, in a production of Corneille’s L’Illusion Comique . She knew she was the only one, but nevertheless believed that art could remain unscathed, that even in war art could preserve its freedom. In the festival bulletin she wrote that she had decided to appear at the festival in order not to lose faith in the possibility of us all working together and that in this way she was saving herself, at least temporarily, from utter despair. ‘Not to play in this performance would mean signing one’s own capitulation,’ she said then, near the end of September 1991. The war had already been raging for several months, Osijek was being bombarded every day, the battle was on for Vukovar, the Federal Army was attacking Dubrovnik. The Zagreb- Belgrade highway was closed to traffic, the trains that used to connect the two cities by a four-hour journey were no longer running: this railway had continued to operate smoothly and regularly throughout World War II but since the summer of 1991 nobody has travelled on it. The mail service was still functioning, one could send letters, but by the autumn it was already impossible to make a phone call from one city to the other. For the last five years M had lived in both cities; she was an actress in the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb but as her husband was working in Belgrade, she used to spend part of the time there, occasionally doing some work in a TV series or a theatre production. It was possible – complicated and sometimes exhausting – but possible nevertheless. She travelled even when the war had already started, as if trying deliberately to maintain at least some ties between the two cities to each of which half of her life belonged.

The newspapers in Croatia published her statement when something tough and cold was already hardening in people. Attacked and driven into basements, they started to bite, to snap, especially at those who did not share their misery. Even before this, suspicions of treason had been poisoning the city like the plague, and in times of greatest danger, when the air-raid sirens howled eighteen times a day, anyone’s absence was seen as cowardly at best, treachery at worst. Fear abolished the right to individual choice and what little tolerance exists in a big city, even at war, simply disappeared, evaporated into thin air. They were out to get her. The first to attack her was a woman journalist who wrote that M was parading her naked breasts on a Belgrade stage while people were being killed in Croatia. A genuine mud-raking campaign against her ensued, in the press, on television, through the grapevine. Perhaps the worst was the accusation that she was a collaborator, a Mephisto, a Gustaf Grundgens who continued to perform in the theatre after Nazi occupation. Overnight M became an enemy, publicly renounced by friends and colleagues. Had she said nothing or returned to Zagreb, things might have been different. She would not now be sitting in New York, thirty-six years old, without work, without anything, having deliberately given up her profession at the height of her career.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Balkan Express: Fragments from the Other Side of War» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.