Since some time passed before the beginning of this action and because the combing through took a long time, the commando found no one else in the area around the village, with the exception of two young women, who were lingering in the sunken terrain in a suspicious way. Leutnant Ullrich surrounded the village and ordered it to be searched. The village inhabitants finally admitted that the Bolsheviks had stayed in the village and claimed that all of the Bolsheviks in the meantime had left the village in the direction of the east. The village inhabitants had obviously supported the Bolsheviks or themselves participated in the sniper attack. Through a translator Leutnant Ullrich made the facts known [eds. the ‘facts’ in this case were merely the Leutnant’s suspicions as noted above] to the assembled population of the village and explained to them the now following reprisal action. He had the draft-age men of the village – altogether 7 men – shot by a rifle salvo from his men in the face of the remaining population and burned the entire village. Leutnant Ullrich’s behaviour from the submitted report is approved by me. It corresponds to the meaning of orders given by me. [14]

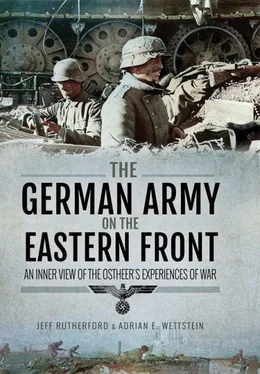

The mass shooting carried out by the artillerymen highlights both the army’s brutal approach to anti-partisan measures, as well as the latitude given to officers in formulating a response. [15]It also illustrates the army’s approach to occupation during the months of the advance. Civilians were seen as irritants and only those deemed threatening received any attention at all from the army. Focused on achieving victory on the battlefield, the German army simply ignored the bulk of the civilian population, only interacting with it when the Germans requisitioned food, needed intelligence, or viewed it with suspicion and fear.

As the German advance slowed in late summer and early autumn, the war behind the front took on a new ferociousness. During the last weeks of August and into the beginning of September, German anti-Jewish policy degenerated into one of pure mass murder. [16]The earlier emphasis on male Jews of military age now evolved into a policy that encompassed all Jews, no matter the age or sex. Large-scale shootings, such as the one at Babi Yar in which over 33,000 Jews were murdered by SS units and Ukrainian auxiliaries, also demonstrated the army’s involvement in the Holocaust. [17]

Recent scholarship has conclusively demonstrated that army units, from the army level down to the regimental level, were involved in the murder of Jews and did so on their own initiative. [18]This was encouraged by army propaganda, which markedly increased in stridency as the army prepared for what it hoped would be the final weeks and days of the campaign in the east. Alongside GerneralFeldmarschall Walter von Reichenau’s infamous order and the similar ones issued by Generaloberst Herman Hoth and Erich von Manstein, the 123rd Infantry Division issued an order of on 2 october first promulgated by Feldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel in late September.

The struggle against Bolshevism demands a ruthless and energetic crack down, especially against Jews, the main carriers of Bolshevism.

Therefore all cooperation between the Wehrmacht and the Jewish population, which is either openly or secretly anti-German, and is used for various preferential auxiliary services for the Wehrmacht, is prohibited.

Passes, which confirm the use of Jews for the Wehrmacht’s purposes, are not to be issued in any case by the military agencies.

The exception is merely the use of Jews in specially constructed labour columns that can only be used under German supervision. [19]

Such orders were an attempt to both motivate the troops for one final effort, and to make clear the stakes of the campaign: Bolshevism and, by extension, Jews constituted a mortal threat to Germany that needed to be eradicated.

The rear-area war against partisans and the development of the Holocaust on the Eastern front soon merged. The following two documents, generated by the 221st Security Division, illustrate the evolution of army policy towards Soviet Jews and how it was entwined with the army’s responses to the irregular resistance. The first dates from July 1941. [20]

On 17.7., a sentry and a motorcycle messenger were shot at in Bialystok by unknown perpetrators.

As a reprisal, Military Administration Headquarters 549 set a comprehensive raid in Bialystok on a day determined independently in agreement with Regional Defence Regiment 45 and the police units in Bialystok that is to be carried out with all severity.

Suspicious people are to be arrested. At the slightest resistance, weapons are to be immediately used. Hostages (especially Jews) are to be taken into custody, whose shooting by the slightest disturbance is to be ordered.

In July, Jews were taken as hostages in response to partisan activity and were the first to be threatened with execution. By September, German policy had already become radicalized, as the following war diary entry from the 221st Security Division demonstrates. [21]

The section Rübekeil reached the final goal of the Bobruisk-Mogilev road in the cleansing action ordered by the Commander [Army Group Rear Command] Centre. During the time period 10-12.9., altogether 2 officers and 160 men were taken prisoner. 1 Communist and 22 Jews were shot due to support for the partisans.

As the report notes, while the army brought in 162 prisoners during the operation, those executed for supporting the partisans were overwhelmingly Jews. Here, the army’s prosecution of the war against insurgents had bled over into the regime’s ideological goals. The fact that both the army and the state not only viewed Jews as the backbone of any resistance in the rear area, but also as the mainstays of the Communist Party and its infrastructure, meant that they disproportionately received the brunt of German anti-partisan brutality during 1941.

The army’s targeted violence and callousness towards the civilians was only exacerbated during the 1941/42 winter crisis. As the army faced an existential struggle to survive the Red Army’s ferocious counter-attack, freezing temperatures, and a supply system that had almost entirely ground to a halt, Soviet citizens in the occupied areas were now viewed in an entirely utilitarian manner. The following record of a meeting at the headquarters of Eighteenth Army’s Chief Quartermaster in December 1941 clearly indicates the army’s total disregard of civilians not seen as useful for its survival.

Prisoners of War. 800,000 tons of bread cereals in a year

Distinction: working prisoners and prisoners in rear camps The number of working prisoners reduced to the absolutely necessary mass. These will be better fed. This comes at the expense of the Heimat.

Question to examine, how few prisoners can I get by with?

All those unable to work are to be deported and not fed.

Make sure that the prisoners really receive the portion they are entitled to.

Treatment of the prisoners should be correct. Currying favour, cigarette exchange is forbidden.

Establish small workshops to improve the clothing, etc. The confiscation of clothes from the civilian population for prisoners.

Civilian population: Feeding is a crime. The wandering of the civilian population is to be stopped with all means. Once again on the order of the Commander-in-Chief, the sharpest separation of the population from the soldiers is pointed out.

At this time, transport of refugees cannot be undertaken. The army cannot help. The civilian population is to be abandoned to its fate.

The fact that Eighteenth Army was carrying out the siege of Leningrad at the same time is surely not coincidental; in both cases, the Germans viewed civilians exclusively within the concept of military necessity and in both cases their fate mattered little in the context of the army’s attempt to achieve final victory on the battlefield. [22]This document, however, also points the way to the further evolution of the army’s occupation policy, as civilians and prisoners of war who could be exploited by the Germans for labour and production were to be mobilized into the German war effort. Such developments, however, would have to wait for the conclusion of the winter crisis.

Читать дальше

![John Stieber - Against the Odds - Survival on the Russian Front 1944-1945 [2nd Edition]](/books/405234/john-stieber-against-the-odds-survival-on-the-russian-front-1944-1945-2nd-edition-thumb.webp)