a) Supply Services

From 20.-26.7., altogether 508 tons of munitions were driven by the motorized supply columns, reinforced by vehicles from the supply company. While doing this, 31,055 kilometres were travelled in 3,111 driving hours , in which every hour of driving averaged a 10km route.

From 20.-26.7., the munitions columns of the Division Supply Leader drove altogether 5 days and 8 hours. For the day, rest and vehicle maintenance accounted on average for only 5 and ¾ hours.

b) Medical Service

During the battle, the deployment of the medical service took on an especially busy and successful form.

It was managed – a record achievement – as a result of the especially favourable location of the main dressing station Ssofijewa, to give final treatment to the wounded of [Infantry] Regiment 19 as early as 1-2 hours after their wounding took place.

After the crossing of I[nfantry] R[egiment] 19 over the Dnieper [River], the 1st Platoon of Medical Company 1/7 was employed on the far side of the river for the first aid and rescue of the wounded. In recognition for carrying out their task while partially in range of direct enemy fire, it received 5 Iron Crosses.

At the main dressing area, 484 wounded and 111 sick, in addition to 107 wounded prisoners of war, were treated during these days.

Field hospital 7 utilized by the 23rd and 7th Divisions treated over 500 wounded during this mission.

Especially worth pointing out is the untiring activity day and night, partially under heavy enemy fire, of the ambulance platoons’ crews.

c) Workshop Company and Fuel Column

The days of battle brought an increased loss of vehicles through direct enemy action, therefore the performance of the Workshop Company rose from a previous average of 80 vehicle repairs per day to 174 on 23.7. (a record day).

The fuel column had especially great efforts to overcome during its path of advance from the [Fourth] Army fuel dump Krupka (one-way distance of 190 km) with dismal road conditions. The section of the fuel column that supplied I[nfantry] R[egiment] 61 during its Dnieper crossing was therefore directly involved in the course of combat.

d) Administrative Service

As a result of the high number of [Fourth] Army and Army troops [3]

subordinated to the division, the demands made on the Administrative Service grew. Instead of 17,000 ration strength, a number for which Administrative Service was equipped for, 24,000 men had to be supplied.

At the time in question, Rations Department 7 provided, outside of meat and bread, some 20 tons of food and 56 tons of oats for each distribution (every 2 days), that had to be picked up from the 100km distant [Fourth] Army rations storage area Krupka.

In this time period, instead of the normal number of 60,000 loaves of bread, Bakery Company 7 baked 82,500 and daily drove 170km with 22 tons storage space for the meal and bread transport.

During the same time, Butcher Company 7 daily drove together a herd of 24 cattle, butchered and prepared altogether 165,000 portions of fresh meat. In addition to that, 7,000 portions of fresh sausage were produced daily by manual work (that means without a sausage machine).

The supply of the combat troops, above all the supply of munitions and the care for the wounded, took place under the most difficult circumstances, whose surmounting demanded the highest efforts. It succeeded thanks to the restless activities of the supply troops, who, in accordance with their strength, were all carried by the will to provide the material foundations for battle and victory to the fighting troops.

These numbers give an idea what quantities of goods were necessary and had to be transported to keep a single infantry division in combat for a week. As the German army in the east fielded some 150 divisions and numerous independent infantry units in summer 1941, one can estimate the enormous task to keep those forces supplied.

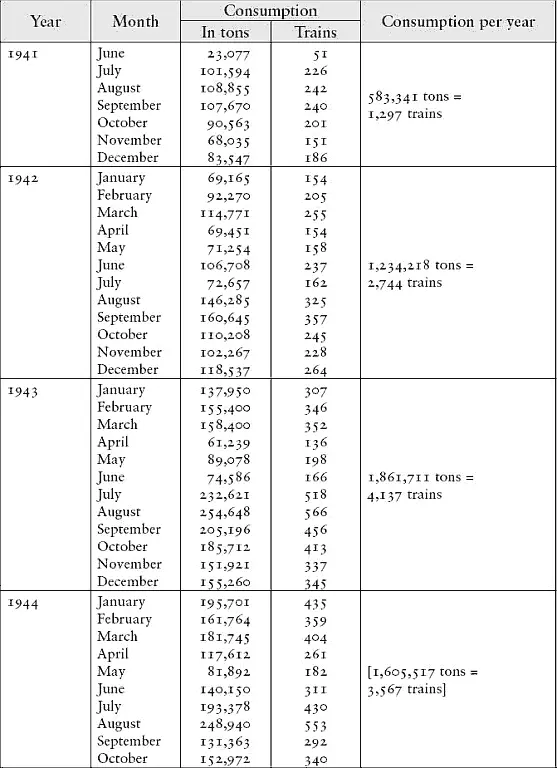

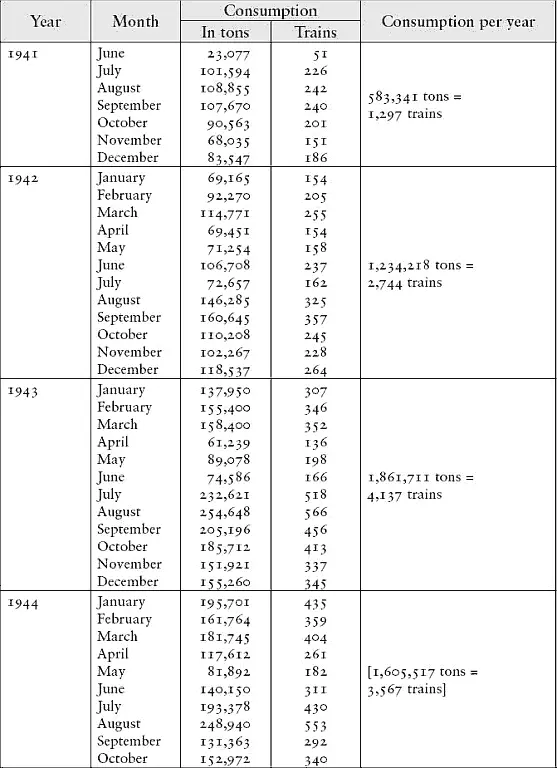

The first required commodity, especially in an industrialized war, was ammunition. The following source gives an idea of the scale of ammunition required by the German army during this conflict: [4]

Total consumption from June 1941 October 1944 (included) = 5,284,787 tons = 11,748 trains

Not only does this table indicate the enormous amount of ammunition spent by the German army in the east as a whole, but it also shows an increase over time. While the average monthly consumption in 1941 was under 94,000 tons, it rose slightly in 1942 to nearly 103,000 tons per month. For 1943 there was a striking jump to over 155,000 tons per month, an increase of nearly 50 per cent. This was strongly driven by the extremely high consumption during the period of July to September 1943, but also by a general increase in ammunition consumption in ten out of twelve months. The highest consumption in July/August 1943 was due to the German summer offensive, Operation Citadel, and the Soviet counteroffensive, which probably represented the culmination of combat intensity on the Eastern front. The enormous increase in 1943 starkly reflected the evolution in German war production from a limited war to a total war with an armaments industry now more thoroughly mobilized and more tightly controlled to achieve a much higher output. However, ammunition production had its major increase in late 1942/early 1943. [5]This explains in part the only slight growth in 1944 to somewhat over 160,000 tons/month. But it should also be kept in mind that by 1944, Germany was much more involved on other fronts than in previous years. There was a constant increase of German engagement in the Mediterranean theatre that accelerated from mid-1942 on and which drew considerable resources away from the east. Even more important for 1944 was the expectation of the Allied invasion in the west. While stocks were built up in France in the first half of 1944, from June 1944 there was a direct competition between the Third Reich’s two primary theatres for all kinds of goods. Despite these circumstances – not to mention the effects of the Combined Bomber offensive – ammunition consumption in the East still increased.

What is also striking from the table was the seasonal pattern of consumption. There was a high consumption in summer (reflecting German offensive efforts and in 1944 a high-intensity defence along the whole Eastern front), a decrease in the autumn (except for 1942 reflecting German defensive action along large parts of the Eastern front) and a low point in late winter and spring. This decrease was often the consequence of winter weather or the subsequent muddy season that emerged during the thaw of spring. Weather, therefore, not only hindered combat, but also the supply of forward units.

In one regard, however, the above list is misleading. Munitions were not simply tons of materials sent to the East, but part of a complex logistical system, since that class of supply goods included hundreds of different items, from rounds for hand guns to heavy artillery shells, from explosives to signal flares. A regular infantry division in 1942 had two calibres for small arms infantry weapons (7.92mm and 9mm), two for mortars (5cm and 8cm), two calibres for infantry guns (7.5cm and 15cm), three for ATG (3.7cm, 5cm and 7.5cm), one for anti-aircraft guns (2cm) and two for artillery guns (10.5cm and 15cm). These were multiplied by different types of bullets (such as tracer or pointed steel-core armour-piercing) and shells (such as high-explosive, armour-piercing, high-explosive anti-tank, and smoke). To further complicate things, the same types of shells and rounds existed in different production versions. [6]In addition, a division had two types of hand grenades, signal rockets, smoke pots, flare cartridges in four colours and various types of explosives. In panzer divisions, the different types of ammunition increased due to the different shells for the tank cannon, and these were often of three or four different calibres. Further up in the command hierarchy, all kinds of army units with their special munitions had to be added, including heavy artillery units. Though it falls outside the bounds of the present volume it needs to be mentioned that the Luftwaffe and the few Kriegsmarine units in the East also needed munitions – and, just like their army counterparts, they also required different calibres and types, such as bombs and torpedoes. While maintaining the regular and orderly supply of German munitions by itself was very complex, it became even more difficult due to the extensive use of captured weapons, as well as the need to supply Allied armies, multiplying the types of required cartridges and shells. This can be illustrated by the situation of the Vth Army Corps in summer 1942. It commanded the German 9th, 73rd and 125th Infantry Divisions, as well as the 3rd Romanian Mountain Division. While all three German divisions needed those types of munitions mentioned above, each also possessed additional weapons. The 9th Infantry Division fielded several batteries of Light Field Howitzer 16, 10.5cm guns as the German standard gun Light Field Howitzer 18, but with different shells. The 125th Infantry Division had a few 4.7cm ATGs of Czech origin and 7.5cm ATG 38/97, the barrel of which was of French origin and needed different shells than the usual 7.5cm ATG 40. All three divisions had 7.65mm hand guns, which added a further type of ammunition to be delivered. The 3rd Romanian Mountain Division fielded few weapons compatible with German munitions, which meant dozens of additional types of ammunition were required. Furthermore, the Corps was responsible for supplying several subordinated army units. Those included two assault-gun battalions that had short and long-barrelled assault guns, each needing different shells even if they had the same 7.5cm calibre. It also included rotating heavy artillery units with 10cm Cannon 18, 15cm Cannon 18 and 21cm Heavy Howitzer 18 and captured Czech 10cm Cannon M35 and 15cm Howitzers M35, as well also two army artillery battalions for coastal defence with captured Norwegian 10.7cm cannon and Dutch 10cm cannon. So, the Vth Army Corps quartermaster staff had to manage the administration and distribution of far more than 100 types of ammunition and to ensure that the right type of shells reached the right gun in time. This demanded thorough planning, but also strained the means of transportation. The consequences of wrongly supplied shells can be seen in a report by the Artillery Regiment 89 (24th Panzer Division) from that time: [7]

Читать дальше

![John Stieber - Against the Odds - Survival on the Russian Front 1944-1945 [2nd Edition]](/books/405234/john-stieber-against-the-odds-survival-on-the-russian-front-1944-1945-2nd-edition-thumb.webp)