He then announced to the wounded Greim that he had dismissed Göring from the post of commander-in-chief of the Air Force and was appointing him in his place.

Marooned, by the whim of the Führer, in the underground complex, the wounded Greim was entirely without the means to command what remained of the air force at whose head he had now been placed. Remaining at the wounded Greim’s bedside in the bomb shelter, Reitsch observed the behaviour of the leaders of the Reich over the following three days. She describes Hitler pacing around the bunker, ‘waving a road map that was almost falling apart because of the sweat from his hands, and planning Wenck’s campaign in front of anyone who happened to be listening to him… His behaviour and physical state sank lower and lower.’

The room Reitsch occupied was adjacent to Goebbels’ office, around which he hobbled neurotically, cursing Göring, blaming ‘that swine’ for all their present troubles, and delivering great tirades to himself. To Hanna Reitsch, obliged to observe and listen to all this because the door of his office remained open, it seemed that, ‘As always, he is behaving as if he is talking to legions of historians who are avidly catching and writing down his every word.’ Her existing ‘opinion of the affectedness of Goebbels, his superficiality and hackneyed rhetorical techniques was fully confirmed by these shenanigans’. ‘Are these really the people who have been ruling our country?’ she and Greim wondered in desperation.

That first evening, Hitler called Reitsch in and said, ‘Each of us has a poison ampoule like this. In case danger approaches.’ He handed her two ampoules, one for her and one for Greim. He added, ‘Each person is responsible for having their own body destroyed so there is nothing left to identify.’

Goebbels’ children, also stranded in the bunker, were told they were in a magic cave with their Uncle Führer and so they were quite safe, protected from bombs and anything nasty. Magda Goebbels, of whom Reitsch saw a lot, ‘was self-controlled most of the time, but sometimes wept bitterly. She thanked God frequently that she was alive and would be able to kill her children.’ She told the pilot, ‘They belong to the Third Reich and to the Führer, and if both cease to exist, there is nowhere left for the children either. But you must help me. What I am most afraid of is that, when the time comes, I will not be strong enough.’

‘From Hanna Reitsch’s remarks we can conclude with certainty’, the American investigator wrote, ‘that Frau Goebbels was just one of the most convinced listeners of the “highly scientific” speeches of her own husband, and the most pronounced example of the Nazis’ influence on German women.’

Hitler, in the presence of those occupying the bunker, presented Magda Goebbels with his own Gold Party Badge, in recognition of the fact that she ‘embodies the truly German woman’ in accordance with Nazi doctrine.

During the night of 26 April the Reich Chancellery was under severe artillery bombardment. ‘The explosion of heavy shells and the crack of collapsing buildings directly above the bomb shelter put everyone under such nervous strain that in certain places sobbing could be heard through the doors.’

On 27 April a friend of Bormann’s, SS Obergruppenführer Fegelein, who represented Himmler at Hitler’s headquarters and was married to Eva Braun’s sister, disappeared from the shelter. Hitler gave orders that he was to be found and arrested. He was captured in his Berlin apartment, wearing civilian clothing and preparing to flee. He asked his sister-in-law to intercede for him, but nothing helped. On Hitler’s orders he was shot by SS men in the Reich Chancellery garden on the evening of 28 April, a few hours before Hitler’s wedding.

On the night of 27 April shelling of the Reich Chancellery continued with even greater intensity. ‘The accuracy of the firing amazed those below,’ Reitsch said. ‘Each shell seemed to land in the same place as the previous one… At any moment the Russians might enter, and the Führer convened a second suicide council.’ There were oaths of loyalty, speeches, assurances that people would commit suicide. In conclusion, Reitsch said, ‘We were told that the SS would be instructed to ensure that no traces remained.’

On 28 April it became known in the bunker from foreign telegrams that Himmler, having assumed supreme authority, had communicated through Sweden to the British and American authorities that Germany was ready to capitulate to the Western Allies.

Heinrich Himmler, Führer of the SS, Protector of the Reich, ‘faithful Heinrich’, ‘Iron Heinrich’, was a traitor. ‘All the men and women were weeping and shouting in rage, fear and despair,’ Reitsch related. ‘Everything got mixed up in a convulsion of insanity.’

A wave of enraged hysteria swept over those present, whom Hitler had doomed to imminent death. According to Reitsch, Hitler ‘was raving like a lunatic. His face was red and unrecognizable. Then he lapsed into apathy.’ Shortly after that, the news arrived in the shelter that Soviet troops were advancing towards Potsdamerplatz and preparing their positions for storming the Reich Chancellery.

Hitler ordered the wounded Greim and Reitsch to return to Rechlin and immediately send all remaining aircraft to Berlin to destroy the Russians’ positions. ‘With air support Wenck will get through,’ he again repeated. Greim’s second mission was to find and arrest Himmler; to ensure he did not live to succeed the Führer. Vengefulness was still capable of galvanizing Hitler.

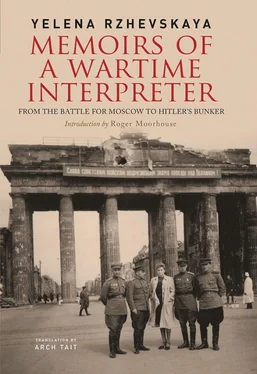

No matter how Greim and Reitsch tried to explain the hopelessness of this mission, Hitler dug his heels in. At the Brandenburg Gate one last Arado trainer monoplane was concealed in a shelter. In it they managed to complete a fraught journey, only to see for themselves the complete collapse of the German armed forces. A few months later an American investigator took down Hanna Reitsch’s description of the flight.

The broad avenue running from the Brandenburg Gate was to serve as a runway. There was a 400 m stretch of roadway that was not cratered. We took off under a hail of bullets and, when the plane climbed to roof level, it was caught by many searchlights and shelled. The explosions tossed the plane about like a feather, but it was hit by only a few fragments of shrapnel.

Reitsch circled to a height of 20,000 feet, from which Berlin looked like a sea of fire beneath them. The extent of the destruction was immense and unbelievable. After fifty minutes they reached Rechlin, where they again landed under fire from Russian fighter planes.

‘Greim gave orders to send all available planes to Berlin’s assistance.’ Having accomplished the first part of his mission, he had now to carry out the second: to find and arrest Himmler. To that end, they flew to Plön [in Schleswig-Holstein], where Dönitz was at that moment, to discover Himmler’s whereabouts. Dönitz had no information. Then they rushed to Keitel and from him learned that Berlin could not count on Wenck: his army was surrounded by Soviet troops. Keitel had sent a message to Hitler to that effect.

Shortly afterwards they heard the news of Hitler’s death and that he had appointed Dönitz as his successor. They then returned to Plön for a meeting called by the new head of the government.

Appointed commander-in-chief of the Air Force by the Führer, Greim was at the meeting when Himmler appeared in the vestibule where Reitsch was sitting. ‘He had an almost playful look about him.’ She stopped him and called him a traitor. There was a dialogue:

‘You have betrayed your Führer and the German people in their hour of greatest need!’

‘Hitler wanted to continue the fight! He wanted the shedding of still more German blood when there is no blood left to shed.’

Читать дальше