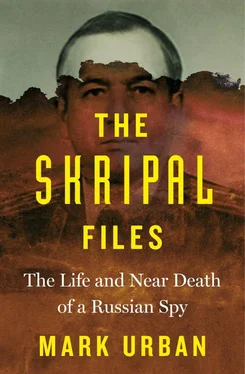

Mark Urban

THE SKRIPAL FILES

THE LIFE AND NEAR DEATH OF A RUSSIAN SPY

The situation that presented itself in March 2018 was one quite unprecedented in my thirty years as a writer. A former Russian spy for MI6 was lying in a coma, having been poisoned by a nerve agent, and the world’s press had descended on a small city in the south of England. The man at the centre of all this was someone I had not only met, but had spent hours discussing espionage with.

He had not been giving me an interview as a journalist. I felt confident he would not have wanted everything blurted out over the airwaves. He had seen me because he knew I wrote books, and wanted to do one about post-Cold War spying. By the strangest turn of fate, back in 1988 I had embedded in a Soviet regiment on operations in Afghanistan that he had previously served in. As our conversations started it was apparent that he knew some of the officers I’d met on this assignment well and this seemed to put him at his ease.

The interviews I’d done with him in 2017 assumed a particular narrative in which a spy swap that took place in Vienna airport in 2010 was central. This was the moment that the former Russian intelligence officer, convicted of spying for Britain years before, had been pardoned and flown to the West.

Roll on several months to March 2018, and everything was looking very different. Worldwide interest in Sergei Skripal had exploded. Who was he? How had he ended up in this incongruous street in an English cathedral city? For a while everyone wondered whether he would survive, then later whether he would simply disappear without ever speaking publicly. Either way, there was fascination in his story. I felt I had to tell it.

Suddenly the wider narrative that I had been researching when pursuing ‘Plan A’ before the Salisbury poisoning, that of an East–West spy battle that had barely slackened after the end of the Cold War, seemed much more relevant too. The result – setting Skripal’s life and the poisoning into this context – is what follows here.

There were many dilemmas along the way, not least whether it was right to do this when there were quite a few issues that I wanted to discuss further with Sergei before pushing ahead. He chose not to speak to me after the poisoning, and doubtless he had many more important matters on his mind. I must therefore take full responsibility for any errors in these pages.

To those who worry that a book like this will inevitably give too much away, you must remember that Skripal was interrogated for two years by the Russian counter-intelligence people, and then put on trial: the outlines of a career as an agent for MI6 that ended fourteen years ago are already very familiar to the Kremlin’s secret servants. My aim is to share some of this knowledge with the public. As for those who believe that this text is too coy in places, or the product of some cosy relationship with our own agencies, the Salisbury events should remind you that lives indeed are at stake. There are also many things in this account that Western intelligence agencies would have preferred to keep quiet.

The experience of previous books about the intelligence world and special forces has taught me that there are some people who would rather these stories were never told, and others who regard anyone who talks to those in the secret world as complicit in some sort of conspiracy. None of these judgements are easy, but there has already been an enormous amount written on this case, and there are reams more of it to come. It’s that someone who has at least met Skripal and followed the intelligence battles of the last thirty years should be writing this. Who knows, one day Sergei or his daughter Yulia may write a book also.

In order to avoid endangering people, I have observed some basic rules: certain people who appear in this book are given pseudonyms (denoted on their first mention by an asterisk, like this: *John Smith); in cases where intelligence sources might be involved, I avoided asking questions about them, still less speculating or hinting at their possible identity; and I have respected the stipulation made by many who gave me information that it should not be attributed to them.

Having faced dilemmas over telling the story, I then had to write it, producing a manuscript quickly in a number of languages while keeping going with the intensive demands of my day job. In this I am very grateful for the support, understanding, and insights that have come from my editors, principally Christiane Bernhardt and Kristian Wachinger at Droemer Knaur; Robin Harvie and Matt Cole at Macmillan in the UK; and Paul Golob and Caroline Wray at Henry Holt in the US.

Jonathan Lloyd put this international publishing deal together while offering expert advice, as he has done without fail during more than two decades as my literary agent. Thanks are also due to Neus Rodriguez, Anya Noble, and Olga Ivshina for their help with research.

I am also grateful to Esme Wren, Editor of Newsnight, for her understanding about how we could report the story for our audience at the same time that I was writing the book.

Finally I must thank my dear wife Hilary, who has come to know all too well that strange, distracted air that comes over me once I become possessed with a book idea. She and our kids have put up with rather too much book-related absenteeism from me, and I am deeply grateful for their indulgence.

PROLOGUE:

AN UNLAWFUL USE OF FORCE

The moment that the Prime Minister rose to her feet was one of utmost seriousness. Benches were lined with members, and a reverent hush descended as she began her statement. Everybody understood the seriousness of what had happened in Salisbury. But what on earth was she going to do?

Theresa May said she was taking the opportunity to update them on the incident, ‘and to respond to this reckless and despicable act’. Flanked by her Home Secretary and the Leader of the House, she paid tribute to the emergency services and the fortitude of the people of Salisbury. That was all very well but what everyone was waiting for was what she was going to say about Russia.

She had chaired a meeting of the National Security Council that morning, and been briefed on the latest intelligence, as well as the state of the investigation. ‘It is now clear,’ she continued, ‘that Mr Skripal and his daughter were poisoned with a military-grade nerve agent of a type developed by Russia. This is part of a group of nerve agents known as Novichok.’

The work of government chemists, ‘Russia’s record of conducting state-sponsored assassinations’, and the assessment that the Kremlin regarded it as quite legitimate to kill defectors had led the UK government to conclude it was ‘highly likely’ that Russia was responsible for the poisoning of Sergei Skripal, a one-time officer in its military intelligence service, and his daughter, Yulia.

Mrs May went on to offer an ultimatum to the Kremlin. It was one that, as a British diplomat phrased it, ‘was designed to be refused’. Either the Salisbury poisoning was a state act by the Russian government or somehow that government had lost control of deadly chemical weapons – which it should not have had anyway under international treaties. Russia was given more than twenty-four hours to respond. If no credible answer was provided, ‘then we will conclude that this action amounts to an unlawful use of force by the Russian state against the United Kingdom’.

Many spectators couldn’t believe what they had just heard. It sounded like 1914, or if not a prelude to war, certainly like the onset of a serious international crisis. To many on the Labour benches it seemed a rush to judgement based on secret intelligence – the very commodity that had been spooned out in Parliament fifteen years earlier to take the country into Iraq.

Читать дальше