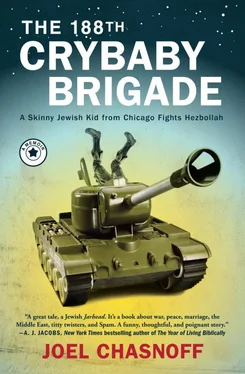

Not exactly military material.

Nor do I have the stomach of a soldier. I pass out when I see blood. If I see somebody throw up, I throw up. I’m something of a worrywart, a trait I inherited from my maternal grandmother, Gramma Ruth, who has spent her life warning me about everything from botulism and flammable pajamas to poisoned Girl Scout cookies and fitted bedsheets. (She’d read in Reader’s Digest that a child could get strangled by the elastic in fitted bedsheets that hadn’t been properly tucked under the mattress.)

But the main reason you’d never expect me to join an army is that I’m a peacenik. I hate guns. I’ve never been in a fistfight in my life. I grew up listening to Peter, Paul & Mary and Simon & Garfunkel, and I truly believe that, as John Lennon said, we should give peace a chance.

In other words, I don’t hate Arabs.

So why would a peace-loving, left-leaning, lactose-intolerant Jew from the suburbs join the Israeli Army?

I grew up with a strong Jewish identity. Like most of my friends, my family was what’s known as Conservative Jews, which basically meant that we picked and chose which rules to follow and made up others as we went along. Friday nights, we ate Sabbath dinner and refrained from watching television, unless there was a Cubs game on. We ate only kosher food at home, but on vacation we ate pretty much everything except pork. This made being Jewish easy and fun: we simply followed God’s commandments until His laws became a pain in the ass.

From kindergarten through eighth grade, I attended a Jewish day school called Solomon Schechter, where I began learning Hebrew at age five. I was always at the top of my class in Hebrew and Torah studies, and not because I was smarter than my classmates, but because for as far back as I can remember, I genuinely loved being a Jew. At school, I volunteered to lead morning prayers as often as I could—so often that my teachers nicknamed me “Little Rabbi.” At the grocery store, I scrutinized the labels on packages of food to make sure every ingredient was kosher. And I couldn’t wait to have a bar mitzvah—not because I was excited for the party, but because it meant I could finally wear the tallis prayer shawl and leather tefillin in synagogue.

When I was six years old, my father’s parents, Zayde Daniel and Bubbie Rose, gave me an illustrated children’s Bible for Hanukkah. I loved my kiddie Bible. Every night, after my parents turned out the lights, I curled up under my blanket with a flashlight to read it. I loved the blood-curdling confrontations with evil Pharaoh, the breathtaking encounters with whales that swallowed men whole. When I read these stories, I imagined I was one of my Bible heroes, marching through the parted Red Sea and turning my staff into a serpent while Pharaoh gasped in fright. When I was eight, I dressed as Moses for Halloween. “T-t-t-t-trick or t-t-t-treat!” I stuttered, but my neighbors didn’t get it. They didn’t know Moses had a speech impediment.

What I loved most about my Bible was that these weren’t just stories, these were my stories. Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were my ancestors. All these wonderful tales were things that had happened to people in my family. And where did all the action take place? In a magical, far-off land called Israel. The thought that I might one day visit this wondrous land was, in my mind, like being told I might one day visit Oz.

Then, in second grade, a miracle happened:

Israel became real.

It was my second-grade Hebrew teacher, Ruti, who made Israel come alive.

Ruti was the first Israeli I’d ever met. She was tall with dark skin, honey-colored eyes, and black hair down to her waist, shiny like a horse’s mane. Ruti was unlike any other teacher I’d ever had. During snack, she ate grapefruits with her bare hands. Unlike my other teachers, who dressed fancy in pantyhose and skirts, Ruti wore sweaters and blue jeans, like us. In spring, when she wore sandals, I could see the cracked, weathered soles of her brown feet—feet that looked as if they’d wandered forty years in the desert on the way to the Promised Land. As far as I was concerned, Ruti wasn’t just Israeli, she was an Israelite, straight out of my illustrated Bible.

Ruti loved Israel, and her love was contagious. Her classroom was decorated with posters of Israel and Israelis: a cluster of Hasidic Jews dressed all in black at the Western Wall; a full moon rising over the Dead Sea; freckled, gap-toothed kibbutzniks in overalls and floppy hats, smiling in the sunshine. Fridays, just before we lit the Sabbath candles, Ruti called us up to her desk, one by one, to sound out Hebrew words in Israeli newspapers. It thrilled me to no end that there was a real, live country out there where the people spoke Hebrew and used money called shekels, just like in the Bible. That I, a Jewish kid in Chicago, could read their newspaper made it even sweeter. Sitting next to Ruti at her desk, her hand guiding mine over the Hebrew letters, I felt connected to this faraway land. I felt as if even though I’d never been to Israel, I had a place there.

Ten years later, I fell in love with Israelis.

I was seventeen years old and visiting Israel on a six-week teen tour. I’d been to Israel twice before, the first time with my father when I was nine, and again four years later with my parents and rabbi. But it was this third trip, as a teenager, that hooked me for life. Like most seventeen-year-olds, I was trying to figure out who I was and who my role models were going to be. Within days of arriving in Israel, I discovered my new heroes: Israelis.

They were the coolest, most exciting Jews I’d ever met. Back home, all the Jews I knew were doctors and lawyers, professors and accountants. But Israelis were different. They rode motorcycles. They smoked. The men were muscly hunks with tattoos and the women were gorgeous. It boggled my mind: here were these people with the same roots as us—yet they looked like supermodels, and we looked like Jews.

Most captivating of all were the Israeli soldiers. Here they were, just a year older than me, flying F-16s, carrying Uzis, and strutting around Jerusalem in olive-green uniforms and Ray-Bans. Compared to them, I felt like such a putz: they defended the homeland like Jewish Rambos while I walked around Israel in sunscreen and a fanny pack. All my life, I kept hearing about how Pharaoh had enslaved us, Hitler had killed us, and the Arabs wanted to wipe us off the map. In these Israeli soldiers, I saw a new narrative: Jews who kicked ass.

By the end of that enchanting summer, I’d decided two things. First, that it wasn’t fair that we American Jews called Israel our homeland but left Israelis to defend it. Second, I made up my mind that I, too, would one day be a soldier standing at the side of the road, hitchhiking with an Uzi slung across my back. Instead of just praying for Israel, I would fight for it. I, too, would be the hero of the Jews.

But there’s one more reason I joined the Israeli Army—and it’s about a girl. Her name is Dorit. She’s a Yemenite-Persian Israeli, with dark skin, curly black hair, and almond eyes—exactly the kind of Mediterranean princess I drooled over when I was seventeen. I met Dorit in January of my senior year of college. She was the Israel programs director at Brooklyn College Hillel, the organization for on-campus Jews; I’d been hired to perform stand-up comedy at the National Hillel Staff Conference in New York. During my show, I noticed her giggling in the back. Afterward, I found her at the pool table and delivered the single greatest pickup line in the history of man:

“Uhm.”

At first, we spoke a couple times a week. Soon, it was every night at eleven on the dot, our conversations lasting into the early hours of the morning. Dorit was unlike any Jewish girl I’d ever known. She was outspoken and fearless, a firecracker of a girl who’d backpacked across America on her own the summer she turned eighteen. After high school, she was a drill sergeant in the Israeli Army. When Saddam Hussein dropped thirty-nine Scud missiles on Israel, it was Dorit’s neighborhood that was bombed—a traumatic experience, no doubt, but for a reason I can’t quite explain, I found this incredibly attractive.

Читать дальше