Never mind that they’d had ‘partnerships’ at the time girls were being abused many years earlier. Never mind that the ‘hindsight’ was actually there in front of so many people, so many officials, in scores of documents that had been left to gather dust.

Mary Doyle, the chief superintendent who ran the later, and ultimately successful Operation Span, said the sort of abuse I’d suffered was a ‘hidden crime’ and a ‘hidden issue’.

John Dilworth, head of the CPS complex case unit in the north-west, said the original decision not to prosecute Daddy and Immy had been reviewed ‘in the light of further information’.

The CPS had simply reconsidered the decision and taken a fresh view. ‘Clearly we regret any decision that is perceived to be wrong, but it was made on the evidence available at that time,’ he said.

The reality, of course, was that the evidence hadn’t actually changed. It was all there: the interviews with me, the forensics, everything. All that had happened was that the CPS decided against taking it to court because they didn’t think I’d make a credible witness, and the police hadn’t bothered to appeal the decision.

So a trial that should have come to court in 2009 didn’t actually make it there until three years later.

And now they just wanted to apologise!

Mr Dilworth was still trying to fight his corner. ‘You cannot say the decision was wrong,’ he blustered. ‘We simply reconsidered the decision and took a fresh view. Clearly we regret any decision that is perceived to be wrong, but it was made on the evidence available at that time.’

Mr Dilworth was asked what was at the root of the decision not to prosecute. Floundering by now, he would only say: ‘The lawyer said that there was not a realistic possibility of conviction.’

It was too much for his boss, Nazir Afzal. Mr Afzal, a British Pakistani and the region’s chief crown prosecutor, rose from his seat away from the panel, beside the assembled media, and took charge.

Reporters craned their necks, surprised by this sudden intervention and sensing that an unexpected hero was about to write himself into their scripts.

He certainly seized the moment, telling his audience: ‘The original decision was based on evidence from the victim in this case. Initially the lawyer formed the view that she would not be credible.

‘I came here last year and I reversed that decision. I decided that she was entirely credible and that two suspects in relation to her should be charged.

‘It is very rare for us to reinstate prosecutions and I exerted that power and the two men were charged.’

The original lawyer had made a judgement: ‘I looked at it completely afresh without any prior knowledge and formed a different view.’

Mr Afzal was asked whether he thought I’d been betrayed. He paused, momentarily, before answering: ‘I have no difficulty in apologising to her,’ he said. ‘She was let down by the whole system and we were part of that in some respects. But we reacted to that as soon as possible.’

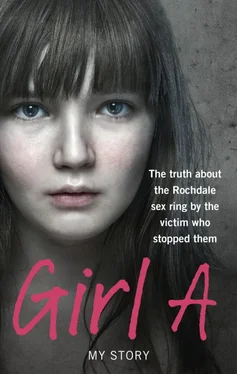

As soon as possible, that is, after the Operation Span team had put pressure on the CPS to re-instate the Girl A case.

Because they’d known precisely how strong it was – that for all they’d clustered other cases, other girls, around it, mine was the one that would form the cornerstone of the entire trial. Mr Afzal realised that and I think, too, he saw the justice of it finally coming to court.

* * *

In Liverpool, the defence was in full swing. After Daddy had been in the witness box, next came Immy, then Tariq, then the rest, all of them denying the ‘lies’ of their accusers.

Then came closing speeches from Rachel Smith and all eleven main defence lawyers and, after that, the summing up of all the evidence by Judge Clifton.

Finally, on 1 May, the jury filed out of Court 3:1 to consider their verdicts, almost all of them looking away as they passed the glass-screened dock to their left.

I’d been told that after such a long case it would take them a while to make their minds up. I crossed my fingers that they would make the right decisions. I knew the men who’d attacked me were all guilty, but would they?

As it turned out, the process wasn’t anywhere near as simple as it should have been.

The far-right protestors had tried to make trouble right from the start of the trial, and now, as it moved towards its conclusion, they were trying one more time.

At first it was just the usual, with seven of them getting arrested outside the court complex. But two and a half days into the jury’s deliberations their idol, Nick Griffin, posted a notorious tweet that would cause legal carnage.

The press tend to have a nose for trouble, and that afternoon they started twitching when the lawyers were called back into court while the public and media were held back at the outer doors.

The media people protested, of course, but it was no use. The ‘Court in Chambers’ sign went up with a flourish from a court clerk and they were left outside to fume.

When the barristers finally came out, reporters sidled up to the ones they knew best, hoping to get a steer. For once, that didn’t work – all they got were mutterings: ‘It’s a scandal,’ said one barrister. ‘We’ve been stitched up,’ snapped another, as he headed towards the lifts.

On a bench, Andrew Norfolk, a reporter from The Times , was sitting with an A4 pad resting on his iPad, putting the final touches to a note to the judge, demanding that the press be allowed into the next session.

It all became clear – well, sort of clear – when the court reconvened, press included. The jury seats, though, were conspicuously empty.

The scandal, it turned out, was this: at 1.53 p.m. Nick Griffin, the leader of the BNP, had posted a comment on Twitter that read: ‘News flash. Seven of the Muslim paedophile rapists found guilty in Liverpool.’

He later backtracked on Twitter after being told the jury hadn’t officially returned any verdicts. But by then the damage had been done.

Judge Clifton was livid. He brought the jury back in, and behind closed doors, asked if any of them had passed on any information about their deliberations. They all said no.

The problem was, though, that Griffin’s tweet about seven convictions was exactly what the jury had decided up to that point.

One by one, the defence barristers rose to say that any convictions now would be tainted. They argued that the jury’s impartiality must have been compromised. The only solution, they said, was to discharge them all and start the whole trial again.

Mr Nichol led the charge. ‘The most reasonable inference,’ he said gravely, ‘is that the confidentiality of the jury’s deliberations has been breached and that someone outside the jury who has an improper interest in the outcome of the trial has been receiving communications from within the jury room.

‘It seems at the very least that if such communication has taken place then it will be two-way traffic. If there has been such improper communication, the independence of the jury is compromised and there has been a breach of their obligation to reach an impartial verdict.’

Judge Clifton listened to all their submissions, but said he was satisfied that none of the jurors had been at fault, either deliberately or accidentally. The tweet had first appeared on the ‘Infidels of Britain’ website, at a time when the jury were in a room where all electronic equipment, including their mobiles, was banned. So he decided the jury should be left to carry on with the rest of their deliberations.

The barristers were furious. ‘It’s not right,’ said one. ‘These men may be guilty, but they’re entitled to a fair trial – and this isn’t fair. It leaves a bad taste in the mouth.’

Читать дальше