I hung about the house for an hour or so, suffocated by my parents’ sympathy and outrage, feeling all the time that, for all that the gang had damaged me, it was me, and me alone, who’d inflicted this upon my little girl. Chloe didn’t deserve this. Not this. And I felt it was me who’d brought her to it.

I couldn’t deal with it.

The thought gnawed away inside me until I reached the point where I couldn’t bear it any longer: I couldn’t cope with the thought of her crying her heart out in that car and then arriving at a stranger’s house, frightened and alone in a new world. Suddenly, I stood up, threw on my coat and rushed out, brushing past Mum and heading out of the back door and on towards the shops up the hill.

At the off-licence, I bought two litres of White Star, then caught a bus to some local woods, thinking about Chloe all the way.

They’re a bit minging, the woods, but everyone knows them around my way, and as a little kid I’d played there in the days before we moved to the seaside. I remember thinking about that as I looked for a bench to sit down on, and it reminded me of Chloe – that she should be there, playing, picking flowers, something she loved to do. But today, all I had was a bottle of cider to keep me company.

The more I drank the guiltier I felt, and the more hopeless and lonely and torn up inside. I wanted all the feelings to end because I just couldn’t cope.

I was drunk by the time I staggered onto the bus heading back towards home. This time, though, I didn’t get off at my normal stop; I carried on to the one by the shops so I could buy some paracetamol.

They only let you buy two packets at a time, so that’s what I did, washing them down with the last of the cider. Then I walked on to the shop closest to home, and bought another two packets.

I took those once I’d sneaked in and gone upstairs. Then I lay on my bed, pretty much out of it, waiting, hoping to die, clutching a photograph of my little girl, the girl whose life I’d ruined.

But the pills and the cider just made me feel sick and I had to rush into the bathroom. My sister, Lizzie, heard me throwing up and ran in. She saw lots of the pills floating in the bath and screamed for Mum and Dad.

When Dad got there he grabbed me around the waist and started to squeeze my stomach so I’d throw the whole lot up. Mum ran downstairs to find her phone and dial 999. I was going in and out of consciousness by the time the ambulance arrived.

It was a pathetic attempt, I know, but, just like the other two times, I really did mean to go through with it. I really did want to die.

But I regretted it as soon as I came round in hospital. Susan came to see me that night. She was off duty, but she still felt close enough to me to come. She sat there, asking why I kept trying to kill myself. ‘You’ve got so much to live for, Hannah,’ she said. ‘You really have.’

In the days that followed, I promised myself that I’d get back on my feet and try, finally, to grow up. I knew I had to, if there was any chance of me getting Chloe back. It wouldn’t happen overnight, though, that much I knew.

* * *

With Chloe in care, it was left to the police, not Social Services, to press for me to be moved out of the immediate area; away from Rochdale. Susan and her colleagues knew that it wasn’t just a question of guiding me through video interviews and VIPER parades. It was about helping me to cope with the day-to-day traumas of my life so that, come the trial, I could go to court and give the evidence that would put my abusers away.

They found a supported flat for me in a different area, and I moved there a couple of weeks later. That’s where I met Richie, a lad I went out with for a few months through the summer. It wasn’t a proper relationship, really: me damaged and pretty much a down-and-out; him homeless if he hadn’t got a place there. He didn’t really have anything going for him apart from being funny.

Richie didn’t drink as much as me – I don’t think many people did. We never really went out, we’d just spend our time together in the flats, his or mine, getting drunk all the time. Sex with him was OK, but it wasn’t great. At least it wasn’t abuse.

It ended in September after we’d gone to a christening and got hammered. I took a fiver out of his pocket to go to the chippy and he found out once I’d got back home. He got mad at me and retaliated by robbing my phone.

Because I was drunk I punched him in the face. A few times. The staff heard the row kicking off and called the police. They arrived just in time to see him head-butting me in the face, so they jumped on him and carted him away. I had blood pouring out of my nose, but I still laughed because it seemed so funny to me, for some reason.

They took me to hospital for treatment, but when they checked the CCTV and saw the earlier bit with me punching him, I got arrested too. I got a caution for it, and Richie and I split up.

Just after that, I got an email from UCAS – the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service – saying the university that had offered me a place was withdrawing it. I suspect Social Services had something to do with it. Maybe they’d said I’d be a liability.

* * *

It was another massive blow, but somehow I started to pick myself up. Maybe I was helped by the people around me trying to drag me back into some kind of normal life ahead of the trial that was expected to start in the following February.

Social Services decided they wanted to monitor me 24/7 so they moved me to a foster place, to live with a couple. That way they could keep an eye on me and get reports from the family I was staying with. I joined Alcoholics Anonymous and went to another parenting group.

Jane was still sticking up for me with Social Services. She said I was under a lot of pressure because of the new police investigation. I saw one report in which she’d written: ‘Chloe is a delightful little girl. This has not happened by chance and shows that on the whole Hannah is doing a good job as her mother.’

In another she talked about the loving relationship I had with her. ‘She is affectionate with her and whenever I have seen her with Chloe I have noted that she responds to her needs in an appropriate manner.’

I think it was 21 September 2011 that I stopped drinking: well, mostly. They’d put me on a drug called Campral to help me, and it seemed to work. They say it restores the chemical balance inside your brain, helps it work normally again. I moved into more supported lodgings the next month, still trying as hard as I could to get my life back.

I didn’t have a drink on Christmas Day, nor on New Year’s Eve. I was having contact with Chloe three times a week – even Social Services could see that I was finally coming back from the bad times, and they started talking about giving me a second chance with the little girl they’d taken from me.

Things were looking better than they had been for a long time.

Chapter Twenty-Three

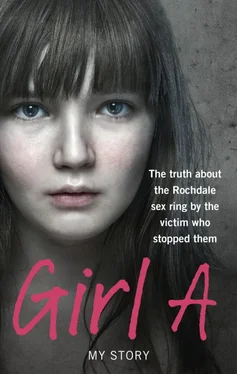

The First Witness

The ‘Girl A’ trial – my trial – was supposed to start on 8 February 2012. The police put me on stand-by and I changed my contact times with Chloe to the weekend, to fit in around it. As usual with Social Services, who were still being obstructive, the police had to push for it for me.

Then I heard it had been delayed. These things often happen, the police told me. Don’t worry. It was only later that I found out the reason for the delay – that two defence barristers, both of them Asian, had suddenly withdrawn from the case. They’d done so because of intimidation by far-right protestors: one of them had been punched by a protestor just outside the court complex, the other illegally filmed in one of the corridors.

Читать дальше