And then, tentatively, I eased the shawl from the side of her face and looked down at her, as she lay in her cot next to my bed. Slowly, I took in her features: the shock of black hair; her nose, just like mine; her lips; those beautiful blue eyes gazing back at me.

‘Hello, Chloe,’ I whispered.

Until that moment, I’d convinced myself that I didn’t really care for her at all. Now, seeing her, holding her, all that changed. ‘What did she weigh, Mum?’

‘Seven pounds, one ounce,’ said Chloe’s proud grandma. ‘She’s perfect, isn’t she?’

I lay there for what seemed an age, holding my baby, pressing my nose against her cheek so that I could inhale her wonderful, unique scent, my mind flooding with the relief of knowing that we could both have a fresh start.

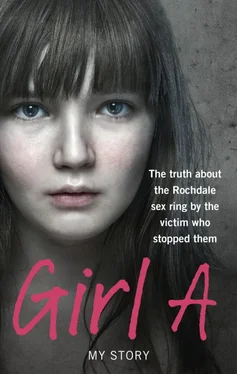

For her, there would be the steadily gathering, simple joy of life while for me, still only sixteen, there was the chance to rebuild my own life away from the misery and pain that had engulfed me for so long. I knew there would be difficult times ahead, but I would try my hardest for her to put the past behind me and give her a future.

As I drifted off to sleep, I recognised there was a part of me that was still damaged, still desolate and still frightened, but I saw, too, that none of that was her fault. An inner certainty told me that no matter how she’d been conceived, she was her own person and fully deserved to have her chance.

The next time I woke up, Dad was there, Chloe in his arms, smiling at me. He’d brought with him a pink blanket that would be so adored by my little girl. It had the image of a teddy bear in the middle, and, as she grew older, she’d take it everywhere with her, always hating to give it up, even to be washed, as if she had a fear of feeling alone in the world. I think she knew instinctively that it wouldn’t be all plain sailing and that with a kid like me as her mum, she’d need that blanket.

My brothers and sisters weren’t allowed to come and visit in the hospital, so they only got to meet her when I came home the next day.

Jane sent me a New Baby card and wrote her number inside, to let me know she still cared and was still there for me. I didn’t feel ready to reply, but I felt glad inside.

Chapter Nineteen

Trying Again

I was asleep with my new baby when the letter from Greater Manchester Police arrived.

It landed on the hall floor like an unexploded bomb that detonated the moment my dad unfolded it and began to read.

I woke up to the sound of Dad ranting and raving downstairs in the living room. Bleary-eyed and aching, I went downstairs to see him waving an A4 piece of paper in his hand. He was crimson with rage.

‘They’ve stopped the case, Hannah! The Crown Prosecution Service say it’s not strong enough. They’re not going to put that bastard on trial. They’re just going to let him go.’

Dad held his arms out to me and I collapsed into them, sobbing, suddenly terrified that my abusers would be free to attack me again.

As my tears soaked into his dressing gown, Dad went on reading bits of the letter out loud. It was dated 25 August, though it turned out the CPS lawyers had actually reached their decision almost a month earlier. The police had taken until July 28 to send them the file and they made their decision not to prosecute the following day.

I could feel Dad shaking with rage as he talked about the DNA the police had from my knickers. ‘You were fifteen , for God’s sake, and he was nearly sixty,’ he said, his voice breaking. ‘How could any jury ignore that? You were under age. They’d have to convict. They’d have no option!’

I was in shock. What would happen to me now, with Daddy and the others completely free?

Mum had come into the room too, and while we sat in a huddle on the sofa Dad rang one of the detectives on the case. He was raging at him about the decision, and then went suddenly quiet as the police officer at the other end of the line explained what he knew about it.

When he came off the phone, Dad said, ‘They didn’t think you’d make a credible witness, kid. And that the men would have just claimed it had been nothing more than consensual sex with a girl who’d gone off the rails.’

I thought of all the evidence the police had gathered: the DNA, the interviews I’d put myself through, the names I’d given them, the addresses, and the detailed, harrowing accounts of being passed carelessly around like a broken doll. They knew about Daddy, about Tariq, and Billy, and Cassie, and all the others.

What more evidence did they want? Why bother interviewing me again in the January if it was going to come to this? Why bother driving around with the police to show them the addresses they’d all taken me to? Why the resulting identity parades?

The identity parades were among the worst things I had had to do.

From the surveillance operations the police had set up of the addresses I’d given them, as well as the locations from the day we’d spent driving around, the police were gradually arresting the men they thought had attacked me. Every so often they would ring and say, ‘We’ve got some more, please come in.’

It made me sick every time.

I did three or four identity parades, or VIPER sessions as they were called, involving about fifteen suspects. I found these VIPER parades, which is a form of identity parade that allows a victim to see line-ups by video, really stressful.

At each VIPER, it was down to me to say whether or not I recognised any of the men in the images that flashed up in front of me. There’s always a suspect in each group of pictures – you’re shown the men’s faces randomly, nine on each disc, I think – and you have to pick the suspect out. If you don’t, they’re allowed to go free. If you’re sure it’s them you say so, and another paedophile is hopefully off the streets. Quite a lot of responsibility, then.

And yet, here I was, back at square one. Why hadn’t the CPS believed me? Or the police? Wasn’t it obvious that I’d been raped? And trafficked?

All in all, at this point it was as if nobody believed me. I thought about all the months it had taken for the police to even get the file to the CPS. I thought about their attitude at the time they were interviewing me; as if they thought that whatever had happened to me I’d brought it upon myself. There was also the fact that Social Services had told my Mum and Dad I was a prostitute; that’d I’d made a ‘lifestyle’ choice.

In their eyes I was just a wayward teenager who’d made the choice to sleep with takeaway workers and taxi drivers in their forties and fifties; to have sex with them one after the other, this way and that way, and then be driven back to a fleapit of a house to recover in time for the next round of ‘fun’.

I felt as though the whole world was laughing at me: the lawyers in their flash offices, the police down at the station, and the men in their taxis and takeaways and grubby flats and houses.

My life had been destroyed, and yet no one was going to pay but me. No one had even bothered to come and see me to break the news. I realised, in those moments, that I’d been abandoned. Again. All that remained for me was a life sentence of fear and ruin.

As Dad threw the letter into the bin in total disgust, I headed back to bed, distraught, paralysed by the fear that now gripped me.

I couldn’t believe it. The police had taken almost a year to get a file to the CPS and the lawyers had decided – in a day, as it turned out – that there was no case against Daddy and Immy. Never mind all the other abusers who’d followed them. Here we were, within days of the anniversary of me first telling the police what Daddy had done to me, and it was all being thrown out.

Читать дальше