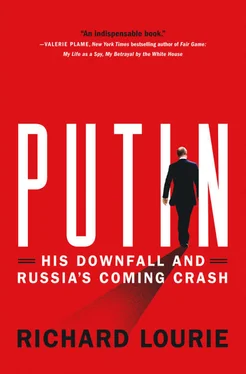

But Putin did not trust. He did not trust the world outside Russia, which in the end he could only see as the enemy at the gates. He did not trust the Russian people out of the fear that they would run rampant if given liberty. But it was a handful of well-educated men who looted the country, not ordinary Russians, who at worst filched a few boards or some cable, and proved themselves sober and canny in Russia’s first real elections. And in the end on some level he did not trust himself sufficiently to manage a freer people in a world that might be opposed at times to Russia but was hardly inimical to it.

He did succeed in restoring stability and a measure of self-respect to Russia after the bitter humiliations of the 1990s, no small achievement. At the beginning of his second term, with high oil prices buoying the economy and his popularity solid and high, Putin could have done something daring and transformative. Using his immense top-down power he could have in earnest begun the transformation of Russia from a petrostate to a twenty-first-century knowledge-based economy—not because a knowledge-based economy is “nicer” and “greener,” but because it is a more dependable producer of wealth over the long run and also because it involves larger numbers of people than the gas and oil industries, thereby making them stakeholders in society. In turn, that sense of belonging and connectedness could have served as the matrix for a new culture from which Russia’s new vision of identity would finally emerge.

The timing was good, the timing was bad. Good from the point of view of Russia’s wealth and Putin’s popularity, bad from the point of view of the world situation. The Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004 might have been seen by Putin as only an internal question if NATO had not at the same time conferred membership on seven former Eastern Bloc countries, three of them former Soviet republics, moving the alliance right up to Russia’s western border. It was then that Putin began to suffer not from a too low sense of danger but from one that would quickly become much too high.

And as people often do in times of threat and jeopardy, Putin reverted to the tried and true, in his case “the power vertical.” His rule started out as authoritarianism lite but became less so with each challenge, culminating in the street demonstrations on the eve of his inauguration in May 2012. Economically, hewing to the tried and true meant sticking with gas and oil instead of transforming Russia into a knowledge-based economy that would have involved large numbers of people. Instead, the state and society ended up separate if not opposed, Russia’s perennial tragic conundrum.

And because it did not involve the people enough, the House of Putin will, like the House of the Tsars and the House of the Communists, sooner or later come crashing down. When and with how much suffering is anyone’s guess. All that is sure is that the Russian people, who outlasted Genghis Khan and Napoleon, Stalin and Hitler, will survive the fall of the House of Putin. Surviving is what Russians absolutely do best.

Aitken, Joanthan. Nazarbayev and the Making of Kazakhstan . London: Continuum, 2009.

Albats, Yevgeniya. The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia—Past, Present, and Future . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994.

Allison, Graham. Nuclear Terrorism . New York: Times Books, 2004.

Amalrik, Andrei. Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984? New York: Perennial Library, 1970.

Andrew, Christopher, and Oleg Gordievsky. KGB: The Inside Story . New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

Andrew, Christopher, and Vasili Mitrokhin. The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB . New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Aron, Leon. Yeltsin: A Revolutionary Life . New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

Armstrong, Terence. The Russians in the Arctic . Fair Lawn, N.J.: Essential Books, 1958.

Baker, Peter, and Susan Glasser. Kremlin Rising: Vladimir Putin’s Russia and the End of Revolution. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2007.

Berdyaev, Nikolai. The Russian Idea . Translated by R. M. French. Hudson, N.Y.: Lindisfarne Press, 1992.

Berton, Pierre. The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole, 1818–1909 . New York: Viking, 1988.

Billington, James. H. The Icon and the Axe: An Interpretive History of Russian Culture. New York: Vintage Books, 1970.

______. Russia in Search of Itself . Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2004.

Blank, Stephen J., ed. Russia in the Arctic . Carlisle, Pa.: Strategic Studies Institute, 2011.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia . New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Browder, Bill. Red Notice . New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015.

Brzezinski, Matthew. Casino Moscow: A Tale of Greed and Adventure on Capitalism’s Wildest Frontier . New York: Touchstone, 2002.

Brzezinski, Zbigniew. Second Chance: Three Presidents and the Crisis of American Superpower . New York: Basic Books, 2007.

Bukovsky, Vladimir. Nasledniki Lavrentiya Beriya: Putin I Ego Komanda . Moscow: Algoritm, 2013.

Chaadayev, Peter. Philosophical Letters and Apology of a Madman . Translated by Mary-Barbara Zeldin. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1969.

Cherkashin, Victor. Spy Handler: Memoir of a KGB Officer . New York: Basic Books, 2005.

Cockburn, Andrew, and Leslie Cockburn. One Point Safe . New York: Anchor Books, 1997.

Cone, Marla. Silent Snow: The Slow Poisoning of the Arctic . New York: Grove, 2005.

Congdon, Lee. George Kennan, a Writing Life . Wilmington, Del., ISI Books, 2008.

Cooley, Alexander. Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia. New York: Oxford, 2012.

De Custine, Marquis. Journey for Our Time . London: Arthur Barker, 1953.

Earley, Pete. Comrade J: The Untold Secrets of Russia’s Master Spy in America After the End of the Cold War . New York: Berkeley Books, 2009.

Eimer, David. The Emperor Far Away: Travels at the Edge of China. New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Emmerson, Charles. The Future History of the Arctic . New York: Public Affairs, 2010.

Freeland, Chrystia. Sale of the Century: Russia’s Wild Ride from Communism to Capitalism . New York: Crown, 2000.

Gall, Carlotta, and Thomas de Waal. Chechnya: Calamity in the Caucasus . New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Gates, Robert. Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War . New York: Vintage, 2015.

Gessen, Masha. Dead Again: The Russian Intelligentsia After Communism . New York: Verso, 1997.

______. The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin. New York: Riverhead, 2012.

Goldfarb, Alex, and Marina Litvinenko. Death of a Dissident . New York: Free Press, 2007.

Goldman, Marshall I. Petrostate: Putin, Power and the New Russia . New York: Oxford, 2008.

______. The Piratization of Russia . New York: Routledge, 2003.

Grant, Shelagh D. Polar Imperative: A History of Arctic Sovereignty in North America. Vancouver, British Columbia: D & M Publishers, 2010.

Gustafson, Thane. Wheel of Fortune: The Battle for Oil and Power in Russia. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2012.

Hoffman, David E. The Oligarchs: Wealth and Power in the New Russia . New York: Public Affairs, 2002.

Hopkirk, Peter. The Great Game . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

______ Setting the East Ablaze: Lenin’s Dream of an Empire in Asia. New York: Kodansha, 1984.

Читать дальше

![Stephan Orth - Behind Putin's Curtain - Friendships and Misadventures Inside Russia [aka Couchsurfing in Russia]](/books/415210/stephan-orth-behind-putin-s-curtain-friendships-a-thumb.webp)