At four-thirty in the afternoon, I left for Ocala, where, at five-thirty or so, I put my time card into the time clock and put the card back in the rack. Now I was free until ten, but I was in Ocala.

Ocala is a small place but it had a nice library. I spent most of my time in the library. If there was a movie playing I hadn’t seen, I went to see it. I saw every movie released from May to September 1985. I also tried to shop for new clothes. All my stuff was old before I went to prison. It was even worse now.

Shopping was really difficult. The big department stores were incredibly intimidating. I saw how much stuff people really needed when I ran the commissary. Nobody needs all this stuff, I thought. The stores were overstocked. They had way too many brands of duplicate products. It was a tragic waste.

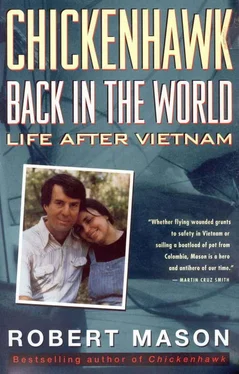

I spent hours looking at shirts, checking prices, trying them on. The result of most of my shopping trips was that I agonized for hours and ended up buying nothing. I couldn’t decide; I’d freeze trying to decide to buy a shirt for twenty-five dollars or one for twenty. I worried myself sick that I’d run out of money. I’d been living on thirty-three dollars a month. Just one decent shirt cost more than that. I had lots of money in the bank, but I had no confidence I’d ever sell another book, and how long would I get royalties from Chickenhawk ? It took me four months to buy four shirts and four pairs of pants. I spent two weeks stalking a mall before I got the courage to buy a pair of running shoes.

By ten I was checked in at the Salvation Army. The television in the front room was permanently tuned to the Christian Broadcasting Company. Jim and Tammy Bakker were the drill on Captain Gerber’s ship. Each night the people in the front room were different. The rule was that indigents could stay one night. They got dinner after a prayer meeting. They got breakfast before they had to leave the next day, no prayers required. These people, men mostly, sat staring at Jim and Tammy telling them how God would help them just like He’d helped Jim and Tammy. Homeless men stared at the effervescent, clown-faced Tammy Bakker with vacant eyes.

One morning, while I made my coffee, I watched a young mother with a baby and a two-year-old eating breakfast. I asked her where she was going. She said she’d go as far as she could walk. One of the benefits of capitalism is that it offers constant reminders of the consequences of failure, especially if you hang around places like the Salvation Army. I felt terrible. I wanted to do something for her, but deciding what to do about her and the others that drifted into this place every day was even tougher than picking out a shirt. I wasn’t able to help. I nodded, poured my coffee, and left. That, I figured, was where I was going to be if I didn’t get another book published.

The routine changed on Friday. Patience came with me to Ocala in the afternoon. I turned in my Xeroxed paycheck from Knox, punched in, and punched out for the weekend. Then we drove to Gainesville and went to the Wine and Cheese Gallery. There, in a small courtyard behind the restaurant, I saw old friends and met new people—none of them felons—musicians, attorneys, professors, computer programmers, and so on. The Friday meetings became a regular thing and I began drinking beer. The Wine and Cheese had a hundred different brands from all over the world, and I probably tried them all over a period of four months. I hadn’t had a drink or a joint or even a cigarette for nearly two years. I’d been detoxed. I wanted to get retoxed.

Saturdays I worked on the cabin. On Sundays I lay around and read until about eight-thirty. Then I’d attempt to choose some clothes to wear at the bunkhouse. I found the task frustrating and irksome. Why do I have to pick what I wear every day? Why doesn’t everybody just wear the same thing?

One Sunday night, after spending an hour agonizing over just what I should wear at the Salvation Army, I said, “Patience. What High Springs needs is a clothing room.”

“What?”

“You know. A place that does all your laundry and gives everybody uniforms. You wouldn’t have to worry if you were in style. The clothes would be cheaper. People would be a lot happier if they had a clothing room.”

Patience looked at me sadly and shook her head.

During July, John Tillerman showed up for his four-month halfway house. He, too, had to get a job, and he chose to be a free-lance carpenter. I hired him to help me finish the cabin. He put in wallboard upstairs, a cypress ceiling downstairs. I installed two air conditioners so our papers and books wouldn’t mildew.

On August 12, 1985, I was released from the halfway house to the custody of the parole office in Gainesville. I met my parole officer, Jack Gamble, at his office in the courthouse. He had been my pre-sentencing investigator, and was a fair man. He told me I couldn’t use drugs. I asked if that included alcohol and tobacco. He said those were fine. I said they kill a thousand times more people than all illegal drugs combined. Gamble nodded and said, “That may be true, but they’re legal.” He continued, saying I had to expect unannounced visits from him; I’d be free to travel anywhere I wanted, with permission. Everywhere except Central and South America. They were afraid I’d smuggle in another load, I guess. All I had to do on parole was submit a monthly statement saying I still lived at the same place and how much I earned that month. Again, the fact that I was paid only twice a year brought complaints from Mr. Gamble’s bosses. “Bob, it looks bad when you say you earned nothing for months at a time,” he said after I’d turned in three reports indicating zero income. When I got my royalty statement from Knox, I made a copy and sent it to Mr. Gamble. I’d made over a hundred thousand and I included a note saying; “In case anybody asks you why I don’t report a monthly income, show them this.” I wanted them to know that I was equally capable of being snotty.

I wrote about 150 pages of the second version of my robot book. I’d changed the whole story. I invented an undercover Russian agent to come to Florida (where the robot was built) to nab the machine. I thought it was pretty good; so did Patience. Knox sent a note back saying, “I just don’t get this, Bob.”

I was invited to give a reading in Chicago in June. Larry Heinemann had arranged it and invited us to stay with them. I was going to meet Larry for the first time and worried that we might not get along. I mean, he’d been wonderful and generous to me, writing to me in jail, sending me books, but what if he turned out to be an asshole in person?

Gamble gave me travel papers and we flew to Chicago, took a cab to Larry’s house. He came out wearing a baseball cap and said, “Welcome to Chicago, Bob. I’m glad you’re out of jail. We got rules here, too. Never pick a fight in a strange bar. Never cheer for the Yankees. And never, ever park your car in the same place twice.” We got along great. His wife, Edie, and Patience clicked, too.

Chicago was having a better-late-than-never welcome-home parade for Vietnam veterans. Neither Larry nor I wanted to go. The Chicago Sun-Times sent Tom Fitzpatrick over to get our feelings about the parade. When Fitzpatrick asked us if we were going, Larry said, “Nope. It’s just another fucking formation to me.”

I said, “Nope. Pilots don’t march.”

Patience was disgusted with us and made us go. “You don’t have to march,” she said. “Just watch. But go.”

We did, and I’m glad. It was heartwarming to see the hundreds of thousands of people who turned out to applaud and whistle and generally behave as though Vietnam vets weren’t losers after all. General Westmoreland gave a speech which Larry and I boycotted. Westmoreland, to me, was a fool whose strategy of attrition—killing people without taking territory—was responsible for that war lasting ten years and costing fifty-eight thousand American lives plus millions of Vietnamese, Cambodians, Laotians, and even Thais. Now he was an old man and I just wanted to leave him alone. Heinemann said I was too kind, and held Westmoreland in such contempt that he probably would’ve choked him if they’d met.

Читать дальше