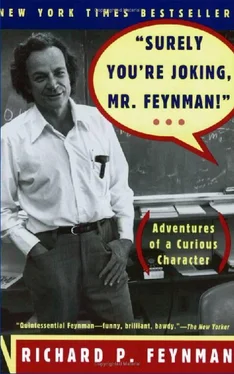

I get all excited: There’s no question but that I’ve got to find out about hypnosis. This is going to be terrific!

Dean Eisenhart went on to say that it would be good if three or four people would volunteer so that the hypnotist could try them out first to see which ones would be able to be hypnotized, so he’d like to urge very much that we apply for this. ( He’s wasting all this time, for God’s sake!)

Eisenhart was down at one end of the hall, and I was way down at the other end, in the back. There were hundreds of guys there. I knew that everybody was going to want to do this, and I was terrified that he wouldn’t see me because I was so far back. I just had to get in on this demonstration!

Finally Eisenhart said, “And so I would like to ask if there are going to be any volunteers …”

I raised my hand and shot out of my seat, screaming as loud as I could, to make sure that he would hear me: “MEEEEEEEEEEE!”

He heard me all right, because there wasn’t another soul. My voice reverberated throughout the hall—it was very embarrassing. Eisenhart’s immediate reaction was, “Yes, of course, I knew you would volunteer, Mr. Feynman, but I was wondering if there would be anybody else. ”

Finally a few other guys volunteered, and a week before the demonstration the man came to practice on us, to see if any of us would be good for hypnosis. I knew about the phenomenon, but I didn’t know what it was like to be hypnotized.

He started to work on me and soon I got into a position where he said, “You can’t open your eyes.”

I said to myself, “I bet I could open my eyes, but I don’t want to disturb the situation: Let’s see how much further it goes.” It was an interesting situation: You’re only slightly fogged out, and although you’ve lost a little bit, you’re pretty sure you could open your eyes. But of course, you’re not opening your eyes, so in a sense you can’t do it.

He went through a lot of stuff and decided that I was pretty good.

When the real demonstration came he had us walk on stage, and he hypnotized us in front of the whole Princeton Graduate College. This time the effect was stronger; I guess I had learned how to become hypnotized. The hypnotist made various demonstrations, having me do things that I couldn’t normally do, and at the end he said that after I came out of hypnosis, instead of returning to my seat directly, which was the natural way to go, I would walk all the way around the room and go to my seat from the back.

All through the demonstration I was vaguely aware of what was going on, and cooperating with the things the hypnotist said, but this time I decided, “Damn it, enough is enough! I’m gonna go straight to my seat.”

When it was time to get up and go off the stage, I started to walk straight to my seat. But then an annoying feeling came over me: I felt so uncomfortable that I couldn’t continue. I walked all the way around the hall.

I was hypnotized in another situation some time later by a woman. While I was hypnotized she said, “I’m going to light a match, blow it out, and immediately touch the back of your hand with it. You will feel no pain.”

I thought, “Baloney!” She took a match, lit it, blew it out, and touched it to the back of my hand. It felt slightly warm. My eyes were closed throughout all of this, but I was thinking, “That’s easy. She lit one match, but touched a different match to my hand. There’s nothin’ to that; it’s a fake!”

When I came out of the hypnosis and looked at the back of my hand, I got the biggest surprise: There was a burn on the back of my hand. Soon a blister grew, and it never hurt at all, even when it broke.

So I found hypnosis to be a very interesting experience. All the time you’re saying to yourself, “I could do that, but I won’t”—which is just another way of saying that you can’t.

In the Graduate College dining room at Princeton everybody used to sit with his own group. I sat with the physicists, but after a bit I thought: It would be nice to see what the rest of the world is doing, so I’ll sit for a week or two in each of the other groups.

When I sat with the philosophers I listened to them discuss very seriously a book called Process and Reality by Whitehead. They were using words in a funny way, and I couldn’t quite understand what they were saying. Now I didn’t want to interrupt them in their own conversation and keep asking them to explain something, and on the few occasions that I did, they’d try to explain it to me, but I still didn’t get it. Finally they invited me to come to their seminar.

They had a seminar that was like a class. It had been meeting once a week to discuss a new chapter out of Process and Reality —some guy would give a report on it and then there would be a discussion. I went to this seminar promising myself to keep my mouth shut, reminding myself that I didn’t know anything about the subject, and I was going there just to watch.

What happened there was typical—so typical that it was unbelievable, but true. First of all, I sat there without saying anything, which is almost unbelievable, but also true. A student gave a report on the chapter to be studied that week. In it Whitehead kept using the words “essential object” in a particular technical way that presumably he had defined, but that I didn’t understand.

After some discussion as to what “essential object” meant, the professor leading the seminar said something meant to clarify things and drew something that looked like lightning bolts on the blackboard. “Mr. Feynman,” he said, “would you say an electron is an ‘essential object’?”

Well, now I was in trouble. I admitted that I hadn’t read the book, so I had no idea of what Whitehead meant by the phrase; I had only come to watch. “But,” I said, “I’ll try to answer the professor’s question if you will first answer a question from me, so I can have a better idea of what ‘essential object’ means. Is a brick an essential object?”

What I had intended to do was to find out whether they thought theoretical constructs were essential objects. The electron is a theory that we use; it is so useful in understanding the way nature works that we can almost call it real. I wanted to make the idea of a theory clear by analogy. In the case of the brick, my next question was going to be, “What about the inside of the brick?”—and I would then point out that no one has ever seen the inside of a brick. Every time you break the brick, you only see the surface. That the brick has an inside is a simple theory which helps us understand things better. The theory of electrons is analogous. So I began by asking, “Is a brick an essential object?”

Then the answers came out. One man stood up and said, “A brick as an individual, specific brick. That is what Whitehead means by an essential object.”

Another man said, “No, it isn’t the individual brick that is an essential object; it’s the general character that all bricks have in common—their ‘brickiness’—that is the essential object.”

Another guy got up and said, “No, it’s not in the bricks themselves. ‘Essential object’ means the idea in the mind that you get when you think of bricks.”

Another guy got up, and another, and I tell you I have never heard such ingenious different ways of looking at a brick before. And, just like it should in all stories about philosophers, it ended up in complete chaos. In all their previous discussions they hadn’t even asked themselves whether such a simple object as a brick, much less an electron, is an “essential object.”

Читать дальше