Rebecca Goldstein - Betraying Spinoza - The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Rebecca Goldstein - Betraying Spinoza - The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Random House, Inc., Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity

- Автор:

- Издательство:Random House, Inc.

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:978-0-80524273-7

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

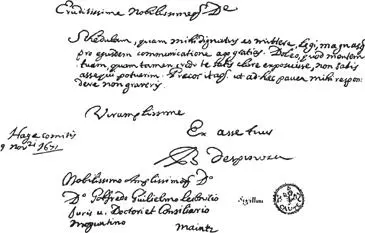

A letter from Spinoza to Leibniz. Note his watchword, caute , in the lower right-hand corner.

Spinoza remained throughout his life, and well into the eighteenth century, a thinker whom one could admire only in secret, hiding one’s sympathy just as his Marrano antecedents had concealed their wayward Jewishness. Open admiration could destroy even the most established of reputations, well into the eighteenth century’s so-called Age of Reason. In the 1780s, for example, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi launched a generalized attack on Enlightenment thought by claiming that the late poet Lessing had been a closet Spinozist, a charge sufficient to compromise the entire movement for which Lessing had been a leading spokesman 3Jacobi even went after Immanuel Kant and his successors, arguing that “consistent philosophy is Spinozist, hence pantheist, fatalist, and atheist.”

The holy furor aroused by the name Spinoza is in contrast to the man’s predilection for peace and quiet. He confessed himself to have a horror of controversy. “I absolutely dread quarrels,” he wrote an acquaintance, explaining why he had declined to publish a work that contains some of the main themes of The Ethics , titled Short Treatise on God, Man, and His Well-Being . 4The signet ring he wore throughout his life was inscribed with the word caute , Latin for “cautiously,” and it was engraved with the image of a thorny rose, so that he signed his name sub rosa . One might argue that the very form of The Ethics , written in the highly formalized “geometrical style” inspired by Euclid’s Elements , is partially designed for the practical purpose of keeping out any but the most gifted of readers, rigorously cerebral and patiently rational.

Spinoza’s ambitions on behalf of reason are staggering: he aims to give us a rigorously proved view of reality, which view will yield us, if only we will assimilate it, a life worth living. It will transform our emotional substance, our very selves. The truth shall set us free. His methodology for exposing the nature of reality was inspired by one of the strands that the seventeenth century’s men of science were weaving into what we now refer to as the scientific method, that magnificently subtle, supple, and successful blend of mathematical deduction and empirical induction. Spinoza was keenly interested and involved in the intellectual innovations that we now look back on as constituting the birth of modern science. His inspiration came from the mathematical component of modern science, not its empiricism. The methodology he believed could reveal it all was strictly deductive, which is not the way that science ultimately went. (Still, there are contemporary physicists and cosmologists who are inspired by the Spinozist ideal of “a theory of everything,” one in which the mathematics alone would determine its truth. String theorists, in particular, pursue physics almost entirely as a deductive endeavor, letting their mathematics prevail over niggling empirical questions. The spirit motivating them is Spinozism, which sometimes makes other scientists question whether what string theorists are up to really qualifies as science at all.)

But if the claims Spinoza makes on behalf of pure reason can strike us as staggering, there are also, staggeringly, a number of propositions that he produced from out of his deductive system that have been, centuries later, scientifically vindicated. A leading neurobiologist, Antonio Damasio, argues in his Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain that Spinoza’s view of the relationship between mind and brain, as well as the complicated theory of the emotions that he deduced from it, are precisely what the latest empirical findings support. Spinoza, despite his non-empiricist methodology, is not scientifically irrelevant.

But there are claims that come out of Spinoza’s deductive system that are even more important for our times, more piercingly relevant, than his happening to have produced a stunningly contemporary answer, through pure deductive reason, to the mind-body problem and given us a view of the emotions that science has caught up with, in thinkers like Damasio, after some three hundred years. What Spinoza has to say about the importance of allowing the discovery of nature to proceed unimpeded by religious dogma could not speak more pertinently to some of the raging controversies of our day, including the recurring public debate in America over Darwin’s theory of evolution. The sides are drawn up now much as they were in Spinoza’s own day.

Just as relevant to current concerns, particularly in America, is his fundamental insistence on the separation of church and state. John Locke, who spent some years in Amsterdam, right after Spinoza’s death, associating with thinkers who had known and been influenced by Spinoza, transmitted this insistence to the founding fathers of America. The spirit of Spinoza lives on in the opening words of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the phrase referred to as the Establishment clause: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

Spinoza placed all his faith in the powers of reason, his own and ours. He enjoins us to join him in the religion of reason, and promises us some of the same benefits — while firmly denying us others — that traditional religions promise. Rigorous reason will lead us to a state of mind that is the height of what we can achieve not only intellectually but also, in a sense — the only sense compatible with his rationalism— spiritually. The aim of his ethics is to give us the means to arrive at a “contentment of spirit, which arises out of the … knowledge of God.” This is the state of mind dubbed “blessedness” by the man who had been known in three different languages — Hebrew, Portuguese, and Latin — by a name that translates into “blessed”: Baruch, Bento, and Benedictus.

It is hard for us to appreciate the loneliness of Spinoza’s secularized spirituality. For an individual of the early seventeenth century to live outside the bounds of a religious identity — to aim to be perceived as neither Jew, nor Christian, nor Moslem — was all but unthinkable; and, in fact, Spinoza did continue to be called, with predictable disdain, a Jew. Huygens, for example, never refers to Spinoza by name in his letters, even though the two often conversed on such fields of mutual interest as mathematics and optics; but rather Spinoza is always “the Jew of Voorburg” or, even more belittlingly, “our Israelite,” “our Jew.”

The social frame of reference enclosing every individual of the premodern era was inherently religious. Spinoza’s choice was an instance of a principle that had yet to be discerned in even the vaguest outline. Part of the horror he invoked throughout Europe derived from the radical stance he assumed simply by pursuing a life with no religious affiliation. Though the Romantic poet Novalis called him, and for good reason, “God-intoxicated,” he was also routinely excoriated as an atheist. He seemed to have been genuinely dismayed by the charge, though his conception of God is sufficiently peculiar — and subtle — that one can see how his constant talk of God might strike even us today as disingenuous, yet another old Marranoist trick of hiding one’s unacceptable beliefs under formulaic insincerities. We should accept Spinoza’s dismay at face value and use it to guide us to understand what he meant by “religion” and “piety,” both of which he nonhypocritically endorses.

The terms of his excommunication were the harshest imposed by his community, uncharacteristically including no possibility for reconciliation or redemption. Though the statement of his excommunication is long on curses, it is short — to the point of silence — on the exact nature of his offenses. Only vague and general “evil ways” and “abominable heresies” are referred to. Were his deviations practical, doctrinal, or attitudinal? The fact that he was so young, with the philosophical results for which we celebrate him now still years ahead, confounds the situation.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.