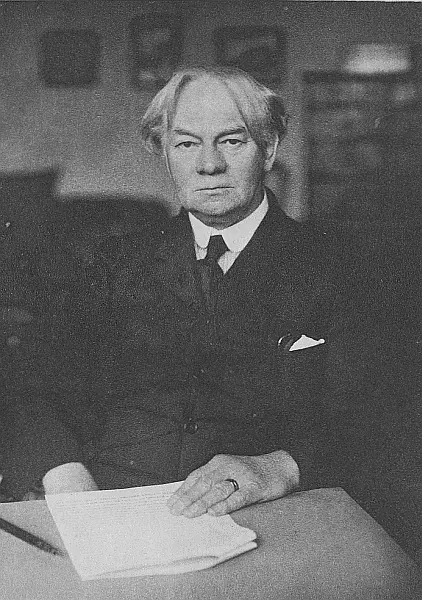

Jerome K. Jerome

My Life and Times

I remember a night in Philip Bourke Marston's rooms. He was blind and wrote poetry, and lived with his old father, Dr. Westland Marston, the dramatist, in the Euston Road. They had turned us out of Pagani's; it must have been about twelve o'clock.

Pagani's was then a small Italian restaurant in Great Portland Street, frequented chiefly by foreigners. We were an odd collection of about a dozen. For a time—until J. M. Barrie and Coulson Kernahan came into it—I was the youngest. We dined together once a fortnight in Pagani's first-floor front at the fixed price of two shillings a head, and most of us drank Chianti at one and fourpence the half flask. A remnant of us, later on, after Philip Marston's death, founded the Vagabonds' club. We grew and prospered, dining Cabinet Ministers, Field Marshals—that sort of people—in marble halls. But the spirit of the thing had gone out of it with poor Philip.

At Pagani's, the conversation had been a good deal about God. I think it was Swinburne who had started the topic; and there had been a heated argument, some taking Swinburne's part and others siding with God. And then there had been a row between Rudolph Blind, son of Karl Blind, the Socialist, and a member whose name I forget, about a perambulator. Blind and the other man, whom I will call Mr. X, had bought a perambulator between them, Mrs. Blind's baby and the other lady's baby being expected to arrive the same week. All would have gone well but that Mr. X's lady had presented him with twins. Blind's idea was that the extra baby should occupy the floor of the perambulator. This solution of the problem had been put before Mrs. X, and had been rejected; she was not going to have her child made into a footstool. Mr. X's suggestion was that he should buy Blind out. Blind's retort was that he wanted only half a perambulator and had got it. If bought out, it must be at a price that would enable him to purchase an entire perambulator. Blind and X were still disputing, when all at once the gas went out. It was old Pagani's customary method of hinting that he wanted to go to bed.

Philip, to whom all hours were dark, guided us downstairs; and invited us to come round to his rooms and finish up the evening. He wanted to introduce me to his old father, who was an invalid and did not, as a rule, come to these gatherings. Accordingly, some half-a-dozen of us walked round with him, including Dr. Aveling (who wrote under the name of Alec Nelson and who had married a daughter of Karl Marx) and F. W. Robinson, the novelist, who was then running a monthly magazine called Home Chimes . Barrie was writing articles for it, and I was doing a monthly “Causerie” titled “Gossips' Corner” and headed with the picture of a solemn little donkey looking over a hedge. At first, I had objected to the presence of this donkey, but Barrie took a fancy to him, and pleaded for him; and so I let him stay. Most of the writers since famous were among its contributors.

In Fitzroy Square we stopped to discuss the advisability, or otherwise, of knocking up Bernard Shaw and taking him along with us. Shaw for some time had been known to the police as one of the most notorious speakers in Hyde Park; and his name was now becoming familiar to the general public as the result of scurrilous attacks, disguised as interviews, that were being made upon him by a section of the evening press. The interviewer would force his way into Shaw's modest apartment, apparently for no other purpose than to bully and insult him. Many maintained that Shaw must be an imaginary personage. Why did he stand it? Why didn't he kick the interviewer downstairs? Failing that, why didn't he call in the police? It seemed difficult to believe in the existence of a human being so amazingly Christian-like as this poor persecuted Shaw appeared to be. As a matter of fact, the interviews were written by Shaw himself. They certainly got him talked about. Three reasons decided us against waking him up on the present occasion. Firstly, no one was quite sure of the number of the house. Secondly, we knew his room was up six flights of stairs; and none of us seemed eager for the exercise. Thirdly and lastly, the chances were a hundred to one that, even if we ever got there, Shaw wouldn't come down, but would throw his boot at the first man who opened the door.

The Euston Road had not a good reputation in those days. I expect it was the cheapness of the locality that kept the Marstons there. Philip made very little by his writings; and his father's savings could not have been of any importance. In those days, if a dramatist made five hundred pounds out of a play, he was lucky. The old gentleman was in bed when we reached the second floor, but got up and joined us in a dressing gown that had seen better days. Philip, a while before, had been sent a present of really good cigars by an admirer; and sound whisky was then to be had at three-and-six a bottle; so everything went merry as a marriage bell. Philip's old father was in a talkative mood, and told us stories about Phelps and Macready and the Terrys. And this put Robinson on his mettle, and he launched out into reminiscences of Dickens, and Thackeray whom he had helped on the Cornhill Magazine , and Lewis and George Eliot. I remember proclaiming my intention of writing my autobiography, when the proper time arrived: it seemed to me then a long way off. I held—I hold it still—that a really great book could be written by a man with sufficient courage to put down truthfully and without reserve all that he really thought and felt and had done. That was the book I was going to write, so I explained. I would call it “Confessions of a Fool.”

I remember the curious silence that followed, for up till then we had been somewhat noisy. Aveling was the first to speak. He agreed that the book would be interesting and useful. The title also was admirable. Alas, it had already been secured by a greater than myself, one August Strindberg, a young Swedish author. Aveling had met Strindberg, and predicted great things of him. A German translation of the book had just been published. It dealt with only one phase of human folly, but that a fairly varied and important one. The lady of the book I met myself years later in America. She was still a wonderfully pretty woman, though inclined then to plumpness. But I could not get her to talk about Strindberg. She would always reply by a little gesture, as of putting things behind her, accompanied by a whimsical smile. It would have been interesting to have had her point of view.

The majority were of the opinion that such a book never had and never would be written. Cellini's book, if true, was mere melodrama. Pepys had jotted down a mountain of trivialities. Rousseau, having confessed himself the victim of an imbecility tolerably harmless, and more common than he thought, got frightened and, for the rest of the book, had sought to explain away his vices, and to make the most of his virtues. No man will ever write the true story of himself; and if he did Mudie's subscribers would raise shocked eyes to heaven, and ask each other if such incomprehensible creatures could possibly exist. Froude ventured to mention the fact that the married life of Mr. and Mrs. Carlyle had not been one long-drawn-out celestial harmony. The entire middle-class of England and America could hardly believe its ears. It went down on its knees and thanked God that such goings-on happened only in literary and artistic circles. George Eliot has pointed out how we dare not reveal ourselves for fear of wounding our dear ones. That the beloved husband and father, the cherished wife, the sainted mother, could really have thought this, felt that, very nearly done the other! It would be too painful. Society is built upon the assumption that we are all of us just as good as we should be. To confess that we are imperfect, is to proclaim ourselves unhuman.

Читать дальше