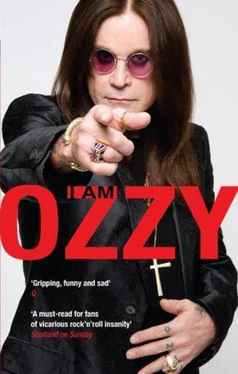

‘Hey, Tommy!’ I shouted.

Tommy looked up, smiled, and walked over to me, flapping his arms for warmth while smoking a fag.

‘Ozzy?’ he goes. ‘Fucking hell, man, it’s you!’

Tommy had worked with me at the Digbeth slaughterhouse. He was one of the guys who roped in the cows before I shot them with the bolt gun. He asked me how long I was in for, and I told him I’d been given three months, but because of my work in the kitchen and my help with Bradley they were going to let me out after six weeks.

‘Good behaviour,’ I said. ‘How long are you in for?’

‘Four,’ he replied, taking another puff on his fag.

‘Weeks?’

‘Years.’

‘Fucking hell, Tommy. What did you do, mug the Queen?’

‘Robbed a bunch of caffs.’

‘How much dough?’

‘Fuck-all, man. But I got a couple of hundred packets of fags and some chocolate bars and whatnot.’

‘Four years for some fags and chocolate?’

‘Third offence. Judge said I hadn’t learned my lesson.’

‘Fucking hell, Tommy.’

A whistle blew and one of the guards told us to get moving.

‘See you around then, Ozzy.’

‘Yeah, see you around, Tommy.’

My old man had done the right thing by not paying my fine. There was no fucking way I ever wanted to go back to prison after Winson Green, and I never did. Jail, yes. Prison, not a chance.

Having said that, I did have a couple of close calls.

I’m not proud of the fact that I did time, but it was a part of my life, y’know? So I don’t try to pretend it never happened, like some people do. If it hadn’t been for those six weeks inside, fuck knows what I would have ended up doing. Maybe I’d have turned out like my mate Pat, my apple-scrumping partner from Lodge Road. He just kept getting involved with heavier and heavier things. Got mixed up with a really bad crowd. Drugs, I think it was. I didn’t know the details, because I never asked. When I got out of the nick I drifted away from Pat, because I didn’t want any more to do with all that dodgy stuff. But every now and again I’d meet up with him and we’d have a bit of a drink and whatever. He was a good guy, man. People are always so quick to put people down, but Patrick Murphy was all right. He just made some bad choices, and then it was too late.

Eventually he turned Queen’s Evidence, which means you take a reduced sentence for ratting on someone who’s more important. Then, when you get out of prison, they give you a new identity. They sent him off to live in Southend or some out-of-the-way place. He was under police protection twenty-four hours a day. But after years of waiting for him to come out of the slammer, his wife broke down and asked for a divorce. Pat goes into his garage, starts up his car, puts a hosepipe over the exhaust, and feeds it through the driver’s window. Then he gets inside and waits until the carbon monoxide kills him.

He was only in his early thirties.

When I heard, I phoned his sister, Mary, and asked if he had been loaded when he’d killed himself. She said they hadn’t found anything: he’d just done it, stone-cold sober.

It was the middle of winter 1966 when I got out of the nick. Fucking hell, man, it was cold.

The guards felt bad for me, so they gave me this old coat to wear, but it stank of mothballs.

Then they got the plastic bag with my things in it and tipped it out on to the table. Wallet, keys, fags. I remember thinking, What must it be like to get your stuff back after thirty years, when it’s like a time capsule from an alternative universe? After I signed some forms they unlocked the door, pulled back this barbed-wire-covered gate, and I walked out into the street.

I was a free man, and I’d survived prison without being arse raped or beaten to a pulp.

So how come I felt so fucking sad?

Knock-knock.

I poked my head through the curtains in the living room and saw a big-nosed bloke with long hair and a moustache standing outside on the doorstep. He looked like a cross between Guy Fawkes and Jesus of Nazareth. And was that a pair of…? Fuck me, it was. He was wearing velvet trousers.

‘JOHN! Get the door!’

My mum could wake up half of Aston cemetery at the volume she shouted. Ever since I’d got out of the nick, she’d been breaking my balls. Every two seconds, it was ‘John, do this.

John, do that.’ But I didn’t want to answer the door too fast. I needed a moment to sort my head out, get my nerves under control. This bloke looked like he was serious.

This could be important.

Knock-knock.

‘JOHN OSBOURNE! GET THE BLOODY—!’

‘I’m getting it!’ I stomped down the hallway, twisted the latch on the front door, and yanked it open. ‘Are you… “Ozzy Zig”?’ said Guy Fawkes, in a thick Brummie accent.

‘Who wants to know?’ I said, folding my arms.

‘Terry Butler,’ he said. ‘I saw your ad.’

That was exactly what I’d hoped he was going to say. Truth was, I’d been waiting a long time for this moment. I’d dreamed about it. I’d fantasised about it. I’d had conversations with myself on the shitter about it. One day, I thought, people might write newspaper articles about my ad in the window of Ringway Music, saying it was the turning point in the life of John Michael Osbourne, ex-car horn tuner. ‘Tell me, Mr Osbourne,’ I’d be asked by Robin Day on the BBC, ‘when you were growing up in Aston, did you ever think that a simple advert in a music shop window would lead to you becoming the fifth member of the Beatles, and your sister Iris getting married to Paul McCartney?’ And I’d answer, ‘Never in a million years, Robin, never in a million years.’

It was a fucking awesome ad. ‘OZZY ZIG NEEDS GIG’, it said in felt-tip capital letters. Underneath I’d written, ‘Experienced front man, owns own PA system’, and then I’d put the address (14 Lodge Road) where I could be reached between six and nine on week nights. As long as I wasn’t down the pub, trying to scrounge a drink off someone. Or at the Silver Blades ice rink. Or somewhere else.

We didn’t have a telephone in those days.

Don’t ask me where the ‘Zig’ in ‘Ozzy Zig’ came from. It just popped into my head one day. After I got out of the nick, I was always dreaming up new ways to promote myself as a singer. The odds of making it might have been a million to one—even that was optimistic—but I was up for anything that could save me from the fate of Harry and his gold watch. Besides, bands like the Move, Traffic and the Moody Blues were proving that you didn’t have to be from Liverpool to be successful. People were talking about ‘Brumbeat’ being the next

‘Merseybeat’. Whatever the fuck that meant.

I ain’t gonna pretend I can remember every word of the conversation I had with the strange, velvet-trousered bloke on my doorstep that night, but it I’m pretty sure it went something like:

‘So you got a gig for me then, Terence?’

‘The lads call me Geezer.’

‘Geezer?’

‘Yeah.’

‘You taking the piss?’

‘No.’

‘As in “That smelly old geezer just shit his pants”?’

‘That’s a very funny joke for a man who goes around calling himself “Ozzy Zig”. And what’s up with that bum fluff on yer head, man? It looks like you had an accident with a lawnmower. You can’t go on stage looking like that.’

In fact, I’d shaved my head during one of my mod phases, but by then I was a rocker again, so I was trying to grow it back. I was pretty self-conscious about it, to be honest with you, so I didn’t appreciate Geezer pointing it out. I almost came back at him with a joke about his massive nose, but in the end I thought the better of it and just said, ‘So have you got a gig for me or not?’

Читать дальше