Ian Kershaw - Hitler. 1936-1945 - Nemesis

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian Kershaw - Hitler. 1936-1945 - Nemesis» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

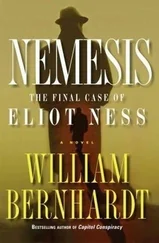

- Название:Hitler. 1936-1945: Nemesis

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-14-192581-3

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Hitler. 1936-1945: Nemesis: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hitler. 1936-1945: Nemesis»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nemesis

Following the enormous success of HITLER: HUBRIS this book triumphantly completes one of the great modern biographies. No figure in twentieth century history more clearly demands a close biographical understanding than Adolf Hitler; and no period is more important than the Second World War. Beginning with Hitler’s startling European successes in the aftermath of the Rhinelland occupation and ending nine years later with the suicide in the Berlin bunker, Kershaw allows us as never before to understand the motivation and the impact of this bizarre misfit. He addresses the crucial questions about the unique nature of Nazi radicalism, about the Holocaust and about the poisoned European world that allowed Hitler to operate so effectively.

George VI thought him a “damnable villain,” and Neville Chamberlain found him not quite a gentleman; but, to the rest of the world, Adolf Hitler has come to personify modern evil to such an extent that his biographers always have faced an unenviable task. The two more renowned biographies of Hitler—by Joachim C. Fest (

) and by Alan Bullock (

)—painted a picture of individual tyranny which, in the words of A. J. P. Taylor, left Hitler guilty and every other German innocent. Decades of scholarship on German society under the Nazis have made that verdict look dubious; so, the modern biographer of Hitler must account both for his terrible mindset and his charismatic appeal. In the second and final volume of his mammoth biography of Hitler—which covers the climax of Nazi power, the reclamation of German-speaking Europe, and the horrific unfolding of the final solution in Poland and Russia—Ian Kershaw manages to achieve both of these tasks. Continuing where

left off, the epic

takes the reader from the adulation and hysteria of Hitler's electoral victory in 1936 to the obsessive and remote “bunker” mentality that enveloped the Führer as Operation Barbarossa (the attack on Russia in 1942) proved the beginning of the end. Chilling, yet objective. A definitive work.

—Miles Taylor At the conclusion of Kershaw’s

(1999), the Rhineland had been remilitarized, domestic opposition crushed, and Jews virtually outlawed. What the genuinely popular leader of Germany would do with his unchallenged power, the world knows and recoils from. The historian's duty, superbly discharged by Kershaw, is to analyze how and why Hitler was able to ignite a world war, commit the most heinous crime in history, and throw his country into the abyss of total destruction. He didn't do it alone. Although Hitler's twin goals of expelling Jews and acquiring “living space" for other Germans were hardly secret, “achieving” them did not proceed according to a blueprint, as near as Kershaw can ascertain. However long Hitler had cherished launching an all-out war against the Jews and against Soviet Russia, as he did in 1941, it was only conceivable as reality following a tortuous series of events of increasing radicality, in both foreign and domestic politics. At each point, whether haranguing a mass audience or a small meeting of military officers, the demagogue had to and did persuade his listeners that his course of action was the only one possible. Acquiescence to aggression and genocide was further abetted by the narcotic effect of the “Hitler myth,” the propagandized image of the infallible leader as national savior, which produced a force for radicalization parallel to Hitler’s personal murderous fanaticism; the motto of the time called it “working towards the Fuhrer.” Underlings in competition with each other would do what they thought Hitler wanted, as occurred with aspects of organizing the Final Solution. Kershaw’s narrative connecting this analysis gives outstanding evidence that he commands and understands the source material, producing this magisterial scholarship that will endure for decades.

—Gilbert Taylor

* * *

Amazon.com Review

From Booklist

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)