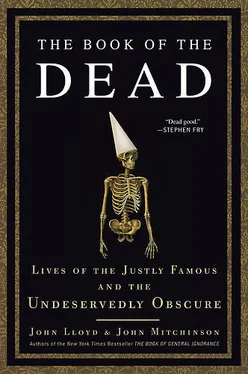

John Lloyd and John Mitchinson

THE BOOK OF THE DEAD

Lives of the Justly Famous and the Undeservedly Obscure

This is a city of shifting light, of changing skies, of sudden vistas.

A city so beautiful it breaks the heart again and again.

ALEXANDER MCCALL SMITH

George Street in Edinburgh is one of the most elegant thoroughfares in one of the best-designed cities in the world. Wherever you stand along it, at one end can be seen the green copper dome of a Robert Adam church called St. George’s and, at the other, a massive stone column called the Melville Monument.

Loosely modeled on Trajan’s Column in Rome, it is not quite as tall as Nelson’s Column in London but it is equally striking and certainly more beautifully situated. The architect was William Burn (1789–1870) but he had more than a little help from Robert Stevenson (1772–1850), the great Scottish civil engineer, better known for his roads, harbors, and bridges—and especially for his daring and spectacular lighthouses. According to the metal plaque near the base of the column, Stevenson “finalised the dimensions and superintended the building of this 140-foot-high, 1,500-ton edifice utilising the world’s first iron balance-crane, invented under his direction by Francis Watt in 1809–10 for erecting the Bell Rock lighthouse.”

The Melville Monument was constructed in 1823 in memory of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville (1742–1811), and it is his statue that glares nobly from the top down the length of George Street. As you might expect from all the trouble the good people of Edinburgh took to put him up there, Dundas was an extremely famous man in his lifetime. A dominant figure in British politics for more than forty years, he was Treasurer to the Navy, Lord Advocate, Keeper of the Scottish Signet, and (an interesting columnar coincidence, this) the First Lord of the Admiralty at the time of the Battle of Trafalgar. On the down side, he was a fierce opponent of the abolition of slavery (managing to successfully prevent it for several years) and has the distinction of being the last person in Britain to be impeached. [1] Impeachment is the process of putting a public official on trial for improper conduct (in this case corruption and misappropriation of public funds) with the intent of removing him or her from office. The House of Lords acquitted Dundas (and offered him an Earldom by way of apology), but he never held office again.

And yet, unless you are a resident of the Scottish capital, or a naval historian specializing in the Napoleonic wars, it is my guess that you have never even heard of him.

Life—what’s it all about, eh?

In Edinburgh, early one sunny morning last August, I was standing at the east end of George Street looking into St. Andrew Square, where Dundas’s memorial stands. The huge fluted edifice rose, dark against the recently risen sun, into the watercolor sky. As I watched, across the grass still bright with dew, ran a small girl, no more than four years old. She was alone, wearing a pink top and white jeans, with blond Shirley Temple curls. She rushed toward the immense column and, when she was a few yards away, she stopped. She looked slowly up its gigantic length till the angle of her head told me she was staring at the blackened figure on the top. Her back was to me—I never saw her face—but from the whole attitude of her body it was obvious that she was awestruck. It was the perfect photograph. Though I didn’t have a camera with me, I can still see it in my mind’s eye as clearly as if it were on the screen in front of me now. It also seemed to be the perfect metaphor. Here were the two bookends of human life. Far up in the sky, long dead, a great stone man whose name very few of us now know; below, still earthbound, still with everything to live for, a tiny real human being whose name is completely unknown to all of us (including me) but who has the potential, if she but knew it, to become the most famous woman in history.

Perhaps in those few moments, staring at the forbidding personage in the sky, something turned over in the tumblers of her brain, opening a hidden lock and inspiring her to future greatness. Or, perhaps, at some subconscious level, she suddenly came to the same conclusion as the Greek philosopher Epictetus: that fame is “the noise of madmen.” After all, it is not necessary for the world to know who you are to live a good and worthwhile life.

John Mitchinson and I hope that you may be inspired to greatness by the journeys of the three score and eight extraordinary human beings here within, or at least draw some comfort from knowing your life is nowhere near as bad as it could be.

JOHN LLOYD

I don’t think anybody should write his autobiography until after he is dead.

SAMUEL GOLDWYN

The first thing that strikes you about the Dead is just how many of them there are. The idea you hear bandied about that there are more people living now than have ever lived in the past is plain wrong—by a factor of thirteen. The number of Homo sapiens sapiens who have ever lived, fought, loved, fussed, and finally died over the last hundred thousand years is around 90 billion.

Ninety billion is a big number, especially when you’re trying to write a book with a title that implies it covers all of them. But it all depends how you look at things. Ninety billion is big, but also small. You could bury everyone who has ever lived, side by side, in an area the size of England and Scotland combined. Or Uruguay. Or Oklahoma. That’s just 0.1 percent of the land area of the earth. And if you piled all the dead people who have ever lived on to an enormous set of scales, they would be comfortably outweighed by the ants that are out there right now, plotting who knows what. It’s all a question of perspective.

The Dead are, literally, our family. Not just the ones we know we are related to: our two parents, four grandparents, and eight great-grandparents. Go back ten generations and each of us has a thousand direct relatives; go back fifteen and the number soars to more than thirty-five thousand (and that’s not counting aunts and uncles). In fact, we only need to go back to the year 1250 to have more direct ancestors than the number of human beings who have ever lived. The solution to this apparent paradox is that we’re all interrelated: the further back you go, the more ancestors we are likely to share. The earliest common ancestor of everyone living in Europe lived only about six hundred years ago, and everyone alive on the planet today is related to both Confucius (551–479 BC) and Nefertiti (1370–1330 BC). So this is a book of family history for everyone.

Trying to organize relatives is always a challenge. The great film director Billy Wilder once pointed out that an actor entering through a door gives the audience nothing, “but if he enters through the window, you’ve got a situation.” With this in mind, we’ve avoided the usual approach of organizing the family get-together into professional groupings: scientists, kings, business people, murderers, etc. This is a perfectly reasonable system, except that, families being what they are, the actors and musicians will be tempted to flounce past the table labeled “accountants” or “psychologists” and vice versa. So we’ve started from a different premise, selecting themes that focus on the quality of lives rather than their content , qualities that are familiar to everyone: our relationship to our parents, our state of health, our sexual appetites, our attitude to work, our sense of what it all means. We also draw no distinction between people with universally familiar names and those who are virtually unheard of. The only criterion for inclusion is interestingness. The results are unexpected bedfellows: Sir Isaac Newton duetting with Salvador Dalí, for example, or Karl Marx singing bass to Emma Hamilton’s soprano.

Читать дальше