For weeks afterwards, Jake still shuddered when people walked up to him and muttered the word clinic. And many did.

SUNDAY, 16 JULY 2006

Camp Bastion

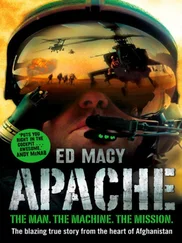

I wanted an immediate debrief with our Hi-8 tapes. I gathered Simon, Jon, Jake and the Ops Officer round the little Sony hand-held to go through them and review the rules of engagement. I wanted to make a particular point about our rounds.

Jake and Jon knew by now that we hadn’t fired into the compound, but I still felt it was important to show them exactly what I’d seen.

All weapon engagements seemed to play out in slow motion to me. I’d been watching gun tapes over and over since 2003. I no longer tried to see if rounds were hitting. I looked at where the line of sight was moving, to see if the range was stable. I looked at all the tiny little things that others didn’t take in because they were too focused on the excitement of targets exploding inside the crosshairs.

On the tiny 4x3-inch screen we saw exactly what we had described to the CO. I pressed the slow motion button as soon as I saw the counter change from 300 to 299. Simon had been recording his TADS image and we were looking at what we’d seen in the Apache, only frame by frame. The round eventually struck and exploded. I let it continue frame by frame for all five rounds.

You couldn’t see the individual rounds, just their heat swirls – and then the explosions. They were separated by 1/10th of a second. It took half a second for all five rounds to impact on the building. Not one of them landed inside the compound.

‘Look at the splash here.’ I repeated the film of the rounds hitting the roof. There was a small hole where each of the shaped charges had gone clean through. ‘Hardly anything,’ I said. ‘But look where this one hit the wall. An impressive splash, but it didn’t penetrate the side of the building.’

I pressed fast-forward and there was a wisp of smoke through the holes in the roof, but nothing from the holes in the walls. Smoke billowed from windows and doors nearby.

‘When you fire at something look at the effect it’s having; only then will you know if your weapons are—’

The canvas curtain parted and the Chinook boys rushed into the Ops tent. They’d just had a call out. They came over to join us at the bird table. The flight had been saved from me rewinding once again.

The Ops Officer ran in from next door, shaking his head. Dickie Bonn was normally so cool I wondered whether he had a pulse. But normal had flown out of the window. ‘It’s Now Zad,’ he said.

The Chinook boys stared at him in disbelief. On their last outing, the Taliban had only missed them by a whisker. They didn’t let it show, but they must have been shitting themselves.

‘Is there a time frame?’ one of the pilots asked.

‘We don’t know that yet.’

Nichol Benzie, on a navy exchange with the RAF, looked at us and grinned ruefully. ‘Here we go again.’

We knew them all by name and got on well, but didn’t really socialise. Everyone pretty much kept themselves to themselves. We’d have a bit of banter when we saw them at Ops, but they tended to stay in their tent and we stayed in ours, even though they were right next to each other.

Partly, we were ashamed to invite them over. The Army Air Corps had a TV set with an old PlayStation underneath, a few books and a couple of magazines; they had stereos, a widescreen surround sound TV, Xbox, Playstations and every game going. We had camp cots lashed together; they had a real sofa. We had cots; they had beds. We had a cool box; they had a fridge. When it came to home comforts, the RAF didn’t fuck around.

We occasionally sat together at mealtimes, but not often. Maybe we didn’t want to intrude. They were at the pointy end of the stick. They got shot at and shot up on a daily basis. There was no slack with them. When they chilled out, we left them to it.

Their mission now, Dickie said, was to take two Chinook loads of troops and ammunition into the DC. Ours was to protect them.

The critical question for us both was when? Could we do it at a time of our choosing? If so, how were we going to skin the cat? Was there a way of catching them on the hop?

The question we were asking ourselves was how were we going to protect them? The short answer was that we couldn’t. We bluffed it last time and the mortars had missed them by no more than a minute.

We were now going to have to search every inch of Now Zad for a mortar base plate, a dish just a metre across with a tube sticking out of it. Thermal was no good: the tube wouldn’t be hot until they fired it, and it was too late by then. We were better off zooming in with a camera, but even then, it was like looking for a needle in a haystack. There were just too many warren-like streets and backyards and alleys.

Where was the obvious place for a firing point? It couldn’t be right on top of the Shrine – that was too close. If they took it away into the Green Zone, we had no chance. They could be sitting under a piece of hessian, listening in to our radios. When they heard a crackle, they’d throw off the cover, fire one off, and throw it back over.

We could do prophylactic firing to try to provoke a response, but we weren’t allowed to fire at targets we hadn’t seen threaten us. We could only fire into empty desert or somewhere we knew for sure was safe.

Nichol shrugged. ‘Right, then, how are we going to do this?’

We could dump the guys in the desert a good distance from Now Zad, and let them make their way in. But they’d have to lug tons of ammunition. They could take vehicles out, but in doing so they’d alert the Taliban to their destination. The Taliban would have bags of time to get into the new firing points and hose the lads to pieces when they tried to get back to the DC.

The only viable option was to land close to the DC. And when it came to LSs, the only remaining option was south-west of the base, protected by friendly fire from the Shrine.

The one thing we knew for sure was that we couldn’t go in daylight again. The Taliban had been fed the Chinooks’ exact grid last time round, and only missed them by seconds. We’d even had a close shave at dusk.

We grabbed the Intelligence Officer. Jerry had catalogued every firing position and every time the Taliban had engaged the DC.

‘When exactly does the firing kick off in Now Zad?’

‘About half an hour after total darkness.’

‘If you were the enemy, and you were trying to set up a firing position into the DC, where would you choose?’

‘Except for today, their firing positions have nearly always been from the north through north-east to the east,’ Jerry said. ‘Never too far out; just around the main town, where they know we can’t follow up.’

‘Okay, so if you’re firing from the north or north-east, how and when are you going to do it?’

‘Taking down an aircraft is still their number one goal. They’ll have weapons in place throughout the day. They’ll only move them if they think you’re not coming. I reckon they’ll drop their weapons just after dusk, as they shift their attention back to harassing the boys on the ground.

‘It’s all part of the same agenda. They want to grind them down, in the hope of ramping up the casualty rate. They know that if they succeed, you guys will have to come in, giving them the opportunity to shoot you down.

’They won’t hang around with a weapon system set up,’ Jerry said. ‘They maintain sporadic fire 24/7, but only start hammering the DC after dark. They’re unlikely to move into the town during daylight because they know they’ll be spotted from above, especially with a heavy weapon.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу