It was in Detmold that I heard from Evert of the martyrdom of my family. It probably would have never happened, nor been so tragic, had they stayed in Germany, to where they had fled in the last few months of the war. They were evacuated, with the wives and children of NSB men or German sympathisers, or as the families of ‘volunteers’. Those measures followed after the French practised the same lynch-law on their own people, after the retreat of the German Wehrmacht in 1944, and as the Armed Forces from northern France neared the Dutch borders. As the Allies marched through France, an aftermath of executions, without a process of law, surged through the countryside. It happened in Belgium too. The Belgians, wanting to see blood, killed around 1,000 of their pro-German people.

The 5 September was a Tuesday in 1944 and three months after ‘D-Day’. “Radio Orange” broadcast from London, that Breda would be the first Dutch city to be liberated by the Allies. It was to be a day of significance for the annals of history and known as ‘Wild Tuesday’, not from the uncountable arrests but from the very loose bullets from the guns of the OD.

In the same month, 65,000 Dutch Nationals, including my parents, in danger of the waves of terror, left Holland for exile in chartered railway wagons. Not all arrived in Germany in one piece. More than once the passengers had to alight from the trains and take cover under the wagons, or find any other sort of shelter. There were low flying aircraft attacks by the Allies, al though it was not military transport. Most of the refugees settled in Lüneburg.

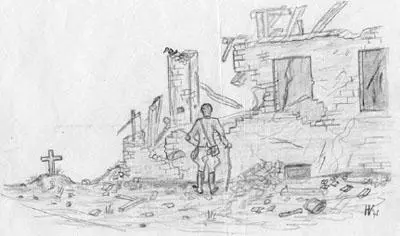

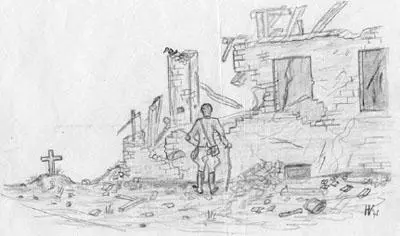

The Verton family however, in Hildesheim, in a former one monastery, joined my sister, who was married to a Dutch ‘volunteer’, an education officer in the SS division ‘Wiking’. I had already visited my sister there, and on that occasion had met British ‘volunteers’ of the Waffen SS. Yes, they were members of the ‘British Freikorps. They had been former members of the bomber-crews, had found themselves in German prison camps, but had declared themselves as ‘volunteers’ to fight against Communism. My family enjoyed the next seven months in Hildesheim, a city of 80,000 inhabitants, until 22 March 1945, a lovely spring day. It was chosen for a bombing raid by 200 four-engined Lancaster Bombers. They destroyed this jewel of a city, with its half-timbered houses, which had been spared up to that time. A 5,000 metre high mushroom of smoke, from fire and high-explosive bombs, could be seen from 300 kilometres away. The city and the monastery were left in ruins. The need for a roof over their heads, and the longing to see their own home again, sent them once more back to Holland, to agony and suffering. There was no military or strategic reason for the bombing of Hildesheim.

Upon their arrival in Holland, all were promptly arrested by the OD. They were responsible for law and order, and wore orange arm-bands. My one year old nephew was torn away from my sister and taken to a special home for NSB children. A notice was at tached to the children’s beds, “Child of the SS” or “Child of the NSB”. They were ‘orphans’, but not orphans. Much later, after my sister was released from internment camp she recorded a tape saying that she had managed to sneak secretly into the home and was devastated at her son’s apathetic and neglected condition.

After two years of internment, she was one of the lucky ones for she could claim her son once more. At three years old she found that he could not walk. Her son was also deaf in one ear. One can assume that he had had painful inflammation of the middle-ear which had not been treated. My sister was lucky that she could collect her son from the home, for many had been adopted. Many of the children were presented for adoption.

Through this sad and sickening time, a thin thread of decency showed itself, from one of the brave. He was one of those brave enough to criticise, to rise above his own experiences of war and take up the sword of decent social behaviour. One such was the Dutch journalist W.L. Brugsma, who had been a resistance fighter and one who had served a spell in a German prison. He criticised the inhumane treatment of these children, and asked, “how clean are those responsible for the Ethnic-Cleansing?” The articles from this man are still suppressed. They belong together with the very sparse literature to be found on this chapter of Dutch history.

On top of the suffering of my family in the internment camps, news reached them of the death of my brother Jan. There are to this day unanswered questions concerning his death. He died on his way to work. He went to work on his motorbike every day, to the German aerodrome where he worked as an electrician. Assassination from the resistance was rife at that time, practised especially on those working for the Germans. It would not have been difficult to acquaint oneself with Jan’s daily routine. In our opinion, he was either the victim of an air raid, from low-flying planes, or the subject of an assassination, from a sniper, just like the father of my friend Robert Reilingh.

For my mother it was a sudden shock. To hear of his death in the circumstances that she was in, was very hard. She was at that time 55 years old. She had fought tooth and nail for the liberation of her family, until she played on the nerves of the camp directors. They then put her into a psychiatric institution in Assen. The Russians too did this with their dissidents. Locked in with the mentally ill, my mother soon became ill, both physically and mentally, as a result of her surroundings, as well as from the separation from her husband and children. She suffered from harassment and very bad nourishment, eating mostly mouldy bread and cooked potato peelings. She had just got to grips with the death of her beloved eldest son, when she then received the news of the death of our father.

My father had had a hernia operation, which was not post-operatively treated during his internment. Instead he was put to work. He had by that time written many letters, optimistic letters, with plans for the future, for when they were released. Some weeks later an obituary circulated amongst the prisoners. It was of my father, an obituary of 59 lines describing his heart felt longing to be re-united with his dear wife and children. His funeral could not have been simpler. We were thankful that one member of the family was present, Evert. An exception was made and Evert, under armed guard, attended the funeral of our father.

Evert had been captured in the area of Arnhem, by the Canadians. They then delivered him to the Dutch, who delivered him into the notorious Harskamp prison. Before he could be sentenced he was put to work in the coal mine. With his escape he avoided the torture that was on the daily agenda. Allied war correspondents took many photos of the war. They took one of Evert, marching at the front of his men as company-leader, upright and marching into the POW camp.

My family were finally released, one after the other in 1947, after two years of internment. Nothing but skin and bone, covered in lice, and careworn, my mother was also released from the Institution in the same year. She spoke unwillingly of her time there. She had a very strong, iron will and this helped her recover, helped her on to her feet and back to her place as head of the family. The youngest of my brothers who was just twelve at this time had spent the two years in different homes, not knowing where any of his family were. He had no news and no visits, which were forbidden. One is duty-bound to mention those who kept to good social behaviour during this misery. One was a doctor who secretly helped my mother. Another was a Jewish jailer, who was sympathetic to one of my brothers and was humane in his behaviour towards him.

‘Homecoming’, a drawing by the author made in 1946.

Robbed of house, home and possessions, the family found a new abode in Woudenberg, in the province of Utrecht. In the countryside, they were surrounded by straightforward and helpful people. They had a very friendly farmer as a next-door neighbour, who even hid my letters to my family. Gradually the family almost returned to normal. Very soon the local police started to pay visits. They wanted to catch either Evert or me on our visits, particularly on public holidays, when they were sure that we would be foolish enough to return. One official would simply have loved to catch us. He accused the family of spying, having found a photo of our model aerodrome that we had built as children in the garden, complete with model planes. We were supposed to be spying on military establishments!

Читать дальше