I travelled with a rucksack and a cardboard case filled with textiles as exchange wares, just as I had in Breslau at the junction of Scheitniger Star. I was once more ‘king’ of the road and the barter business. My expenses from the firm did not run to anything like a good square meal on the way. It was nothing more than a potato cooked in its jacket and spiced with a little salt. This pomme de terre was cold, the carriage was cold and my fingers were blue with the cold. I ate it usually just after the train rolled out of the station, in the hope that I could replace it with something edible from the farmer, on arrival. There was no heating in the train, for many a window was broken, or did not have any glass in it at all. Many were provisionally repaired with cardboard or wood but the wind whistled through the carriages nonetheless. Others could not be moved, up or down, because the leather strap for this had been cut off by passengers and taken away, most probably to sole a pair of shoes.

The whole population was now a caravan of merchants, all travelling hundreds of miles for corn, flour, potatoes or apples, anything to fill those groaning stomachs. Perhaps if one was lucky, one took possession of a bundle of dried tobacco leaves, for a puff or two. In every carriage of the train, small textile or household businesses were represented with tools, saucepans or an iron, rugs, underwear or suits as exchange wares for the farmers.

Such train journeys were not without danger and led to many accidents. A permit most certainly did not ensure you a seat. Every inch of the train was used as one, be it by climbing on to the roof, sitting on the buffers, or clinging for dear life on to door handles whilst standing and journeying on the running-board. All the ways were as dangerous as the other. For those on the roof, a tunnel meant lying flat and holding on tight in order that you were not blown away. For this far from luxurious method of travel, I invested in a pair of motorbike goggles against the soot and black smoke from the steam-engine, not only to protect my eyes, but in order to see better. When I found that there was no seat for me, then I always favoured the buffers between the carriages, where there was a little protection against the wind.

A situation that I experienced in Berlin is burned into my memory. For me it represented the basic instincts of man and took place in the almost destroyed transit station. At 11 o’clock at night, the station looked like something out of the Balkans, or a soldiers’ camp. Everywhere were bodies, men and women snatching sleep, with their arms tightly holding the treasures of that day against thieves. All were waiting for the next train, which departed at three in the morning.

As the train slowly rolled into the roofless station, there was an eruption of movement and a flood of people stormed the train. People shoved, people were pushed, elbowed and all fought for a place on the train. They screamed and fought one with another like animals. One man I saw paid the penalty of using his ingenuity, climbing in through a window, half in and half out, someone saw the opportunity of a lifetime and, from behind, helped him out of his shoes. Decent behaviour or consideration, if brought up with it, was in this situation worthless. One had to reduce yourself to that basic instinct just like everyone else.

Another time I had to journey home on the running board of the train and experienced at first hand the depths that basic instincts sink to when hungry and in need, from people in despair. I hung on, with my precious bundle strongly held between my knees. The quality of coal was not the best and public transport suffered. Second-grade coke fired the furnaces of the steam-trains and this poor quality showed itself when pulling a heavy load uphill or around bends. The train puffed its way nearly to a standstill. Those standing with their treasures on the outside of the train, were subjects of attack, from people who had reconnoitred and were standing at those points, armed with long sticks with hooks. They tried their best to snatch whatever they could away from you. Many a bundle changed hands this way, in trying to ward off the attacks with hefty kicks.

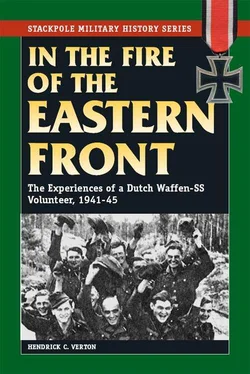

One of my journeys to Berlin forced me into the lions den, i.e. the Dutch Consulate. I had enough cheek to ask for one of those CARE packets, even as a bogus ‘displaced person.’ It was dangerous being on ‘Dutch soil’, so to speak, I could have been arrested, but nothing ventured, nothing gained, and I was not asked for any proof identity. As a German soldier I had no right to this treasured parcel, a ‘generous gesture’ from America. But my cheek paid off and I walked out of the Consulate with one under my arm. So it should not be wondered at, when some time later I was ordered to register myself in Berlin, for my name was on a wanted list. I was accused of entering foreign service without the permission of Her Majesty. That ‘Her Majesty’ had deserted her land and her people, whereas I had defended both from Communism, would not be a debatable point or argument, and so I ignored this.

I was deeply moved by the sight of the city of Berlin, the old capital city of the Third Reich. No matter in which direction one looked its destruction stretched for miles and miles. In the Zoo there was not one tree standing. It was nothing more than the bones now of the capital that it had once been. Bones that had been licked clean of its charm, culture, and its beautiful facades. Stripped of its character it stood derelict from horizon to horizon. Berlin had died, been mercilessly killed. The former American Consul for Germany, Vernon Walters, on a visit in October 1945, declared that “Not even the war damage that I saw in Italy can compare with that which I have now seen in Berlin. It resembles a crushed skull”.

German discipline and industriousness came to the fore, an example shown by the Trummer-Frauen. They were the women who for nearly six years, had hidden in cellars by night to survive the bombing of the Allies. They had taken over the important work left behind by their soldier husbands. At the same time they brought up their children. They showed the world that it was time for a new start. They sorted half a brick here, a whole one there, and threw them into piles. From houses that had once been, they were now symbols of reconstruction.

I only learned later about the battle for Berlin. I heard from French volunteers, who had like me, volunteered to fight against Communism and who, in Kolberg and especially in Berlin had given their last drop of sweat and blood for the cause. Their sacrifice is without comparison. In the centre of Berlin, it was the ‘Charlemagne’ who fought to their last man and destroyed sixty enemy tanks. The American historian Cornelius Ryan reports in his book, The Last Battle, that nearly 100,000 women were raped in Berlin, by Russian soldiers. A further 6,000 committed suicide rather than live under the rule of the Bolshevik régime. At that time the ‘missing persons’ list increased out of all proportion, as the people of Berlin were dragged from their homes by the Reds and transported away to the East.

I was to experience the extreme contrast of misery and amusement at that time. Hundreds froze and starved in the extremely cold winter of 1946/47. The old people were the sacrifices, not having the strength to trudge cross-country with a rucksack for their needs. That was one side of the picture and the other presented itself in the amusement of the newly presented American way of life. I ventured one evening to the area around the railway station, ‘Berlin Zoo’, to take a look for myself. Already in the early evening I heard the ‘swing and jazz’ oozing from the murky underground bars and clubs. It was an offence to the ears of every normal German. They were newly formed in the cellars of the houses. In those bars, a bottle of whisky cost the princely sum of 800 marks. The well-nourished ‘kings of the black market’ enjoyed the spoils of their unscrupulous business deals. Needless to say, there were the highly made-up madams, who were willing to hop around, to ‘jitter-bug’ with the crew-cut styled and sweat-bathed GIs in an ecstasy of wild movement, which released all their inhibitions.

Читать дальше