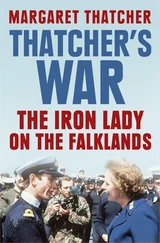

Affluent middle-class homeowners, relatively highly educated and concerned for the education of their children, with a strong Jewish element – this was to be Mrs Thatcher’s personal electorate. These were ‘her people’, who embodied her cultural values and whose instincts and aspirations she in turn reflected and promoted for the next thirty years. One can only speculate how differently her career might have developed if she had become Member for Maidstone or Oxford or Grantham; as it was she became perfectly typecast as Mrs Finchley.

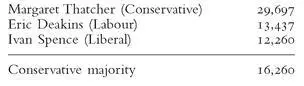

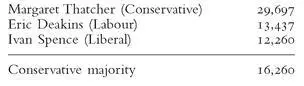

The Thatcher family was on holiday on the Isle of Wight in early September 1959 when Macmillan called the election. Margaret hurried back to throw herself into what the Finchley Press hyperbolically dubbed ‘the political struggle of all time’. 30Her election address spelled out in conventional terms how eight years of Conservative Government had made life better for the voters of Finchley. She fought an energetic but courteous campaign, sharing platforms with both her Labour and Liberal opponents. The result was never in doubt. The Liberals’ effort was enough to gain them some 4,000 votes from Labour but not quite enough to put them into second place: they made almost no impact on the Tory vote. Mrs Thatcher thus increased the Tory majority from 12,825 to 16,260.

Though she held the seat without serious alarm through various boundary changes for the next thirty-two years, her majority was never so large again. The lowest it ever fell was in October 1974, when it dipped below 4,000; but even in her years of dominating the national stage her majority in Finchley never again hit five figures.

Finchley was a microcosm of the national result. Macmillan increased his overall majority to exactly 100.This was the high point of Tory fortunes in the post-war period, a zenith of confidence not to be touched again until Mrs Thatcher’s own unprecedented run of three consecutive victories in the 1980s. The party she joined at Westminster in October 1959 was riding high; political analysts wondered if Labour would ever hold office again. But within a few years the pendulum had swung, and the first fifteen years of Margaret Thatcher’s parliamentary career were served against a background of increasing uncertainty and loss of confidence within the party – from which it fell to her, eventually, to lead an astonishing recovery.

WITH the Conservatives winning a three-figure majority, Margaret Thatcher was one of sixty-four new Tory Members elected in 1959. Among such a large new intake being a woman was simultaneously an advantage and a handicap. As one of only twelve women Members on the Conservative side of the House (Labour had thirteen) she was immediately conspicuous – the more so since she was younger, prettier and better dressed than any of the others – but for this very reason she was also patronised and disregarded. ‘She appeared rather over-bright and shiny’, one contemporary recalled. ‘She rarely smiled and never laughed… We all smiled benignly as we looked into those blue eyes and the tilt of that golden head. We, and all the world, had no idea what we were in for.’ 1

She was always combative, another remembered, but in those early days she would generally back down gracefully when she had made her point. The alternative was to be written off as strident and bossy. She had to be careful to keep this side of her character out of sight for the next twenty years while she climbed the ladder: not until she was Prime Minister did Tory MPs come to enjoy being hectored by a strong-minded woman. To a remarkable extent she succeeded, while extracting the maximum advantage from her femininity.

Mrs Thatcher’s parliamentary career received a fortunate boost within a few weeks of arriving at Westminster when she came third in the ballot for Private Members’ Bills. This threw her in at the deep end, but also gave her the opportunity to make a conspicuous splash: instead of the usual uncontroversial debut delivered in the dinner hour to empty benches, she made her maiden speech introducing a controversial Bill. Inevitably she seized her chance and made certain of a triumph. She brought herself emphatically to the attention of the whips, demonstrated her competence and duly saw her Bill on to the Statute Book with the Government’s blessing. Behind the scenes, however, neither the origin nor the passage of the Bill were as straightforward as they appeared. The newly elected thirty-four-year-old endured some bruising battles, both in the House of Commons and in Whitehall; and the measure that emerged was neither the one she originally intended nor the one she introduced. It was a tough baptism.

An MP who wins a high place in the Private Members’ ballot is swamped with proposals for Bills which he or she might like to introduce. The issue Mrs Thatcher eventually chose was the right of the press to cover local government. This was thought to have been enshrined in an Act of 1908. Recently, however, some councils had been getting round the requirement of open meetings by barring the press from committees and going into a committee of the whole council when they wanted to exclude reporters. The 1959 Tory manifesto contained a pledge to ‘make quite sure that the press have proper facilities for reporting the proceedings of local authorities’. 2But the Government proposed to achieve this by a new code of conduct rather than by legislation. Mrs Thatcher considered this ‘extremely feeble’ and found enough support to risk defying the expressed preference of the Minister of Housing and Local Government, Henry Brooke, and his officials.

Her problem was that she needed the Department’s help to draft her Bill; but the Department would only countenance a minimal Bill falling well short of her objective. Eventually she settled for half a loaf. Her Bill published on 24 January 1960 was judged by The Times ‘to have kept nicely in line with Conservative thinking’. 3In fact, it was a fairly toothless measure which increased the number of bodies – water boards and police committees as well as local authorities – whose meetings should normally be open to the press; required that agendas and relevant papers be made available to the press in advance; and defined more tightly the circumstances in which reporters might be excluded – but still left loopholes. It was still open to a majority to declare any meeting closed on grounds of confidentiality.

The Second Reading was set down for 5 February. To ensure a good attendance on a Friday morning, Mrs Thatcher sent 250 handwritten letters to Tory backbenchers requesting their support. She was rewarded with a turnout of about a hundred. She immediately ignored the convention by which maiden speakers begin with some modest expression of humility, a tribute to their predecessor and a guidebook tour of their constituency. Margaret Thatcher wasted no time on such courtesies:

This is a maiden speech, but I know that the constituency of Finchley which I have the honour to represent would not wish me to do other than come straight to the point and address myself to the matter before the House. I cannot do better than begin by stating the object of the Bill…

She spoke for twenty-seven minutes with fluency and perfect clarity, expounding the history of the issue and emphasising – significantly – not the freedom of the press but rather the need to limit local government expenditure. Only at the very end did she remember to thank the House for its traditional indulgence to a new Member. 4

Читать дальше