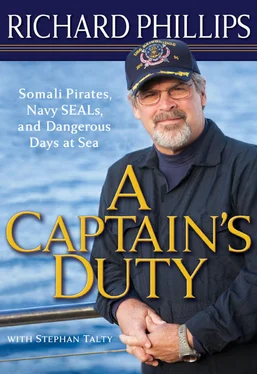

Richard Phillips

with Stephan Talty

A CAPTAIN’S DUTY

Somali Pirates, Navy SEALs, and Dangerous Days at Sea

To all those who go to sea: the U.S. Navy,

the Navy SEALs, the Merchant Mariners.

I am proud to be among them.

To my family: my wife, Andrea, and my

children, Daniel and Mariah, who helped

teach me patience.

Last, to my mother and father, who raised

me to believe.

If fear is cultivated, it will become stronger. If faith is cultivated, it will achieve mastery.

—John Paul Jones, merchant mariner and Revolutionary War hero

The heat in the lifeboat had become completely unbearable. The last drops of cool ocean water from my escape attempt had evaporated off my skin hours ago and, even though it was two in the morning, the heat was radiating off the hull and pressing down on me. I felt as if I were sitting on top of the equator. I’d stripped down to my khakis and socks, but I couldn’t even put my feet on the deck because it was boiling hot. My ribs and arms were aching, too, from the beating the pirates had given me, absolutely batshit furious that their million-dollar American hostage had almost gotten away.

I could see the lights of the navy ship through the aft hatch, dipping up and down on the ocean swells astern, about half a mile away. I’d almost made it. If the moon hadn’t been so bright, the pirates would never have spotted me. I should have been drinking a cold beer in the captain’s quarters right now, telling my adventure story to half the crew and waiting for my call home to go through.

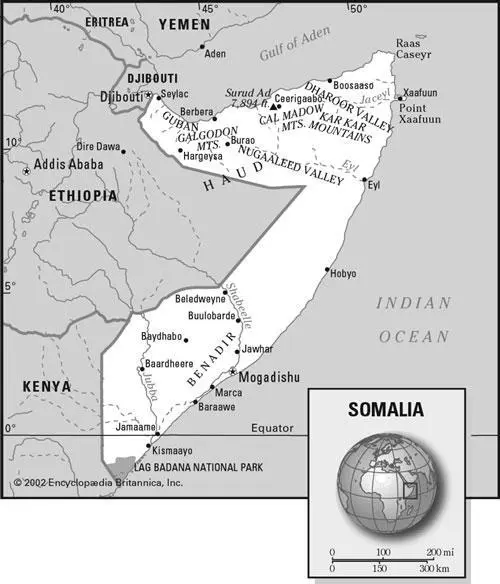

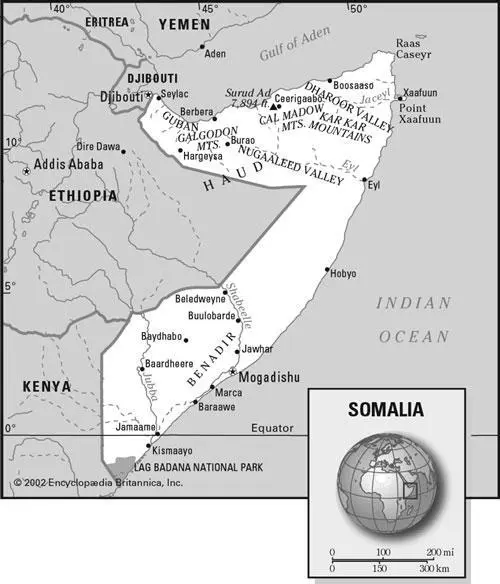

The ship looked gigantic out there. It was like a piece of home floating so close it seemed unreal. It appeared to be a destroyer, which meant they had enough firepower to blow a thousand pirate ships back to Mogadishu. Why hadn’t they done anything?

The hard plastic of the molded seats was digging into my back and causing my legs to cramp. I hung my head back, trying to relieve the stress on my neck. I was now trussed up like a deer in the middle of the lifeboat. The Somalis had lashed my hands to a vertical bar at the top of the lifeboat’s canopy and bound my feet together. I couldn’t even feel my fingers. The lanky pirate, the one I called Musso, had pulled the ropes so tight I’d lost sensation in less than a minute. My hands were starting to swell up like a pair of clown gloves.

I’d been better.

I stood there, panting, counting the minutes go by. I could hear the creaking of the boat and the slap of waves against the fiberglass hull.

Then, suddenly, the whole atmosphere in the boat changed. Nobody said a word, nobody moved. I couldn’t see much anyway, just the eyes of the Somalis and their teeth when they smiled or spoke. There was a little moonlight coming in through the hatches, fore and aft, but I could feel the atmosphere change in a split second. It was like an electric switch had been flipped from positive to negative. When someone has a loaded AK-47 pointed at your face, you get to know his mood really well, believe me. If he’s happy or annoyed, if his nose itches, if he’s thinking about breaking up with his girlfriend, whatever. You know. And my skin just felt a change in the air—like something dangerous had slipped into the boat and was sitting right next to me.

I could catch glimpses of what was going on, but mostly it was what I heard. The first thing was a click . The sound was coming from the cockpit of the boat, where the Leader was sitting. Click. Silence. Click. Silence. Click, click. He was pulling the trigger of his 9mm, dry-firing it. In the darkness, I couldn’t see if the gun was pointed at me, but I felt a cold sensation creep across my chest. The little bastard didn’t have a clip in the gun, or my head would have exploded in a big red spray against the hull. No bullets in the chamber, either. Yet.

And then out of the darkness I heard the chanting. From the cockpit, the Leader called out something in this droning voice and the other three—Tall Guy, Musso, and the crazy-eyed Young Guy—answered him. I leaned forward, trying to figure out what they were saying. It was obviously some kind of religious ceremony, like a Latin Catholic Mass back in Massachusetts when I was growing up. A few hours ago these guys had been laughing and telling jokes and boasting how they were “real Somali sailors, twenty-four/seven.” You could almost forget they were pirates and I was their hostage. Now everything was different. It was like we’d gone back ten centuries and they were asking Allah for his blessing for what they were about to do.

I knew what was happening. But I didn’t have to sit there and take it.

“What are you going to do now, kill me?” I yelled up to the Leader. In the darkness, I could hear him laugh—I saw the flash of his teeth—and then he coughed and spit. Then the four of them went back to the chanting. I tried to move my hands and loosen the rope, but I had to give it to Musso. He could tie a goddamn knot like nobody’s business.

The prayers came to an end, just like that. The boat was quiet and I could hear the splashing of the waves again. I stared into the darkness, looking to see the muzzle of an AK-47 being raised toward me. Nothing.

“You have a family?”

The voice was mocking, self-assured. He was the Leader, no question.

“Yeah, I have a family,” I said. I realized with a feeling of panic that I hadn’t said my good-byes to them. I bit down on my lip.

“Daughter? Son?”

“I have a son, a daughter, and a wife.”

Silence. I heard some rustling up near the cockpit. Then the Leader spoke again.

“That’s too bad,” he said. He was trying to rattle me. And he was doing a damn good job of it, actually.

“Yeah, that is too bad,” I shot back. Whatever they did or said, I couldn’t let them know they’d gotten to me.

Musso came toward me down the aisle of the lifeboat. He took some white cotton cloth that he’d torn from a shirt and laced it through the ropes around my hands. He didn’t pull them tight, just twined them around the ropes. Then he took out some parachute-type lines, one red, one white, and started lacing those through. Slowly. His face was maybe a foot from mine and I could see him concentrating hard on what he was doing. The white and red lines were looped around in this intricate pattern that he had to get exactly right.

It’s a weird feeling, watching yourself being prepared to die. It was like they expected me to go along with my own murder, to be a good victim and not say a word. I felt a jolt of anger shoot through me. These guys were not going to take me away from my family, from everything and everyone I loved. No way.

When Musso was done, he walked back to the cockpit. The Somalis started talking again—regular conversation this time—and they seemed to come to some kind of an agreement. I saw the Leader hand his pistol to Tall Guy, who came walking down the aisle toward me. So he’d been chosen to do the job.

Tall Guy sat down behind me on the orange survival suit. For some reason, they had to be standing or sitting on something orange or red during the ritual. He checked the 9mm clip, slammed it back in, and then played with the gun. It was like he was toying with me. The one I called Young Guy, the one who’d been staring at me the whole two days, smiling like a deranged maniac, came over and dragged my feet onto the exposure suit. At the same time, Musso came down and started tugging hard on my arms. They were trying to get me in the right position, I guess, for a clean killing. The Leader was shouting at Musso, “Pull tight!” and then at the other guy, “Get him up!” Musso yanked on the line that tied my hands, trying to get my arms above my head. They wanted to stretch me out. No goddamn way, I said to myself. I’m not going to be your fatted calf.

Читать дальше