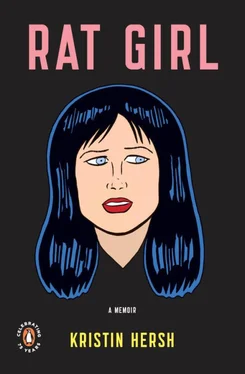

“I do want people to know I’m from California! It’s better than here.” The guy keeps writing, showing no sign of paying any attention to us, ever. I look at Leslie. “I think both our accents drop our IQ’s a bunch of points, though.”

“Try ‘gross’ instead,” suggests Tea.

“ He’s so gross ,” Leslie whispers, then clears her throat and steps up to him. We stand behind her. The door guy looks at Leslie like he hates her. “Hi! We’re Throwing Muses, the band that’s headlining tonight,” she says sweetly in bouncy Californian. “That was us onstage, sound checking. There’s our poster on the wall next to you with a picture of us on it.” Silence. They never talk. “So anyway, nice to meet you,” she continues. “Apparently, we sort of don’t look like a band, but… that’s who we are.” Laughing weakly, she pauses to let this sink in. “And we’re underage, but we’re still: Throwing Muses . The band that’s headlining tonight.” He stares over our heads. We look at each other.

It’s painfully obvious that the three of us are sandy, salty little islanders—beach kids who don’t belong here in Providence, the Big City. We’re clean and healthy, which is very uncool. And we don’t hide it by trying to look like junkies, which is what you’re supposed to do. Our clothes might be dirty, but our bodies are clean, inside and out. We practically smell like sunshine.

We know this is dumb, but it’s dumber to lie about it. Also, for some reason, we dress like old people, or refugees, which makes us look… I don’t know, easy to beat up? Club guys love to hate us, anyway; they bully us with silence. As if they could scare us, for christ sake.

“So, listen,” I tell him, “we’re going out for a while, but we’ll come back in time to play the show, okay?” I study his face for evidence of comprehension. “Tonight. In your club.” He looks away. “Hello?”

Jumping into his line of vision, Tea tries to annoy him into paying attention. “We just wanted to make sure we wouldn’t have any trouble getting back in, ’cause we don’t have ID’s, but we’re still, you know, that band.” She points at our poster. “That band that wouldn’t shut up, right? Heh heh … so you’ll remember us?” she asks. The guy finally nods reluctantly.

Later, though, he displays marked symptoms of short-term memory loss. He squints as we pose in front of our poster, trying to look like ourselves, pointing out our equipment sitting on the stage and the fact that we’re supposed to be on in ten minutes.

“Please remember us,” we beg. “We’re the people that asked you to remember us, remember?”

Tea vibes him under her breath. “ Let… us… in! ”

“It was just a little while ago, remember a little while ago?” I say. “It was right before now!” Throwing up my hands in frustration, I try once more. “Is there someone else back there we could talk to? Somebody who actually talks?” He stares blankly and gestures toward the “Must Be 21 Years of Age or Over” sign. “Yeah, we’ve seen that,” I tell him.

“Why’s live music associated with alcohol at all ?” mutters Leslie, who doesn’t drink. “It’s insane that we can’t get in to our own show because of drinking laws. We should refuse to play.”

“Like anybody’d care,” I grumble.

“Why don’t we have fake ID’s?” asks Tea.

Leslie stares at the door guy, looking thoughtful. “Maybe he doesn’t speak English.”

Eventually, we have to pool our money and buy tickets to our own show. For four years, we’ve been buying tickets to our own shows. Apparently, it’s okay to be underage if you spend money, which is also how it works with drinking. The other bands get pitchers of beer in the dressing room and we get pitchers of orange soda, but nobody’s ever tried to stop us from buying beers at the bar, which is where I’m headed.

While I wait for my drink, I realize I can’t move—I’m stuck between two drunk frat guys who are squeezing me so hard I can barely breathe. They’re the rich kind of frat guys: brand-new baseball caps and expensive clothes, trying unsuccessfully to focus their eyes, shattered by the alcohol in their bloodstreams.

I ask them politely to shift, but instead, they move in closer and one of them pulls off my hat. “Blue hair! Is all your hair blue?” He laughs, surrounding the three of us in a beery cloud, then shoves me into his dumb-ass buddy, who’s concentrating hard on trying to wind an arm around my waist. The guy’s arm slips and he falls off his stool, pushing me back into the first guy, who takes off his baseball cap and carefully balances my hat on his head.

I always want guys like this to fall in love with each other—they have so much in common! And it would solve so many problems.

portia

portia

like frat boys who sleep together

we party better

we know what it means to be a brother

I grab my hat, duck under the other guy’s arm as he tries to steady himself on the bar stool and leave without my drink. I don’t need it. If I go onstage without a beer, somebody in the audience’ll buy me one. They’re mystifyingly kind. But I still stare at the stage like I always do before we play, terrified, thinking What the hell am I doing here? I’m not the type.

I get really bad stage fright, ’cause I’m so shy and ’cause I really don’t understand what happens up there—I can’t prepare for it, it’s too freaky. So I picture the audience as an amorphous horde, waving clubs and torches and yelling at me. But look at ’em: they’re happy as clams and sweet as pie and they buy us beer. I’m just a sissy.

And this is interesting: they aren’t the unruly mob they appear to be at first glance. They’ve neatly organized themselves into little factions. The front row is the most overtly enthusiastic. They’re often drunk, but they’re never drunks—they can think thoughts and string sentences together, and then jump around like psychos. I wonder if they do this in real life, too: in the middle of conversations suddenly jump up into the air screaming, pounding on the guy next to them and running around in circles.

The goth chicks who knit in the back of the room are lovely, soft-spoken and graceful, and they appear to be music appreciators, chatting during shows and then thanking the band politely afterward. They’re nice to look at, with their knitting needles flashing, their black lips and white lips.

Directly in front of the knitters are the hippies. Well, neohippies. The kids of either real hippies or CPAs, they’re friendly, harmless, a little soft around the edges. It’s hard to tell hippie chicks from hippie guys; they all have the same hair, the same voice and the same clothes, none of them wear makeup, and they all dance like goofballs. When they aren’t dancing, they’re sitting on the floor like they’re at a sing-along.

Musicians gather in front of the hippies. There are two different kinds of musicians here in Providence: one kind’s lost in a scene, the other kind’s lost in space. The ones lost in scenes are easy to pick out ’cause they look like they sound—their outfits match their musical styles. I find this bizarre. I like the confused, spacey musicians better. Non-competitive and sweetly scared, their carriage implies a question: what happens next? Both male and female musicians wear eyeliner.

Then come the junkies, precious to me. A ghostly group but livelier than you’d think, they don’t really have a “look.” They don’t look anything like the people who try to look like junkies—they’re just sort of unwashed. I put them on the guest list because they’re dear to my heart and ’cause they really don’t have shit.

Читать дальше

portia

portia