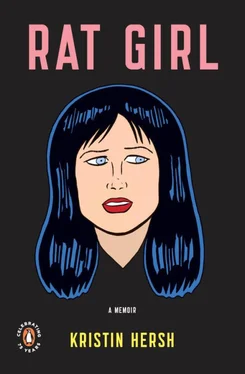

Gil and I decided that our only rule for recording vocals is: no singing. Works for me. Singing’s stupid, at least when I do it, but evil… maybe I shouldn’t call it “evil” anymore because there’s something okay about the mess, the chaos, the noise. It does seem to be an intelligence. I ask myself Dr. Syllables’ question, “Are you peaceful?” and think, Well, yeah, I am peaceful . Peace just isn’t necessarily quiet.

I have to remember what I learned playing guitar on the edge of the bathtub all those cold mornings in Boston: fully engaged efforts toward life pummel the universe into a shape that suits them—they are the universe, after all. So it’s in a song’s nature to leave an impression. I shouldn’t expect anything less.

Now I have to be as bad-ass as a song or a baby. If I’m gonna leave inertia behind, that is. I silently promise this baby that I’ll be ready for forward movement when the time comes.

And I will be. Because vital means you can do both dirty and clean. Science measures art: this studio helped us harness our chaos. The ability to navigate a pristine or polluted terrain is inherent in our changeable natures: strong people can breathe anything and they can live anywhere, like snakes. Light and dark are two different moods a mind shines on the subject matter at hand. All humans embody this dichotomy and music’s just what that sounds like.

None of this is special; it’s merely extraordinary. It’s falling in love—with this moment, with all moments.

status quo

status quo

So I don’t write songs to describe what it’s like in here; it’s just like this in here so that I can write songs. And I absolutely did not invent them.

Sitting in a tree, I look out over my swing set, over other trees and into the fields behind our house.

A cloud of birds erupts from one of the trees: a hundred dark birds, scattering up into the sky.

We’ve reached a détente with the chef: we’re allowed to boil water. This way, Gil can have his buckets of tea and Leslie can have her ramen noodles. Anything else, the chef gets to put on a plate. She’s calmed down a little, seems to have figured out that we aren’t assholes, though we all still avoid eating when she’s around.

This morning I told her I just wanted an apple, so she put one on a plate, then insisted on “making the baby breakfast.” It was very sweet of her, especially since she’s not a very sweet person. I’m just not hungry and she makes me so nervous, I don’t think I could eat the baby breakfast even if I was hungry. Maybe I can smuggle it out in a napkin to the little animals in the barn. I’ve been looking for a way to get them to like me.

The record is really flying along now, though we’re still amazed that we can play a transcendent take and then a crap one. We “identified our curve,” alright: it’s a disintegration that is both instantaneous and remarkable. Crap takes vary in their crappiness, but there’s rarely anything actually wrong with them except “feel”—they simply don’t have it.

After five years of playing shows, we thought we were in love with music and music loved us back. But music’s been waltzing into the room, sparks flying, giving us big, fat kisses and then waltzing right back out again, leaving us very much alone. None of us can put our finger on the mechanism behind the spark. It’s either there or it isn’t and everyone can hear the difference; a dead body may have all its parts intact, but no soul animates it and we all know what that looks like. Luckily, we only need each song to waltz into the room once.

And every time we get a keeper take, Gil lets us take a break so we can wander out to the barn to see the animals. None of us would ever go, say, read a book or make a phone call because the petting zoo babies are so painfully wonderful. Their facial expressions alone are enchanting—like the fish in the aquarium plus goofiness. I can’t believe anybody ever finishes a record with all this dangerous cuteness around. Baby animals’ll keep you from getting anything done.

In the barn, Leslie always climbs a ladder into the hayloft. An actual freakin’ hayloft. She loves it up there. And Tea and Dave position themselves on the fence at the calves’ pen. Perfect, tiny cows, the calves have mouths full of hay and big old purple tongues that stick out when they chew. They’re really beautiful.

But the lambs are my favorites; they run around like they don’t have knees. The lambs’re so much like the toddlers in my midwife’s waiting room, it’s uncanny. This is how vegetarians are born, I guess. I sit on the floor, holding a lamb on what’s left of my lap because they like to be held. The lamb snuggles up against my big belly and bleats at the other lamb as it runs by, kneeless. “We’re never gonna finish this record,” I say. “It’s too cute here.”

“Murder,” says Dave vaguely, his chin on his arms.

“Just ‘murder,’ that’s it?” asks Tea.

Leslie calls down from the hayloft, “Don’t you wanna kill anybody specific?”

“When I kill them, it’ll be specific,” says Dave. “For now, I just wanna book a murder.”

I squint at the back of Dave’s head. “What’re you guys talking about?”

He turns around. “Future crimes,” he says, bending down to scratch my lamb under the chin.

“I’m gonna free lab animals,” says Tea.

“Well, god, Tea, you could do that now. It can’t be that hard…” The lamb looks over at me and bleats, sticking out his little, pink, potato chip tongue. I laugh. “He likes me ’cause I gave him bacon.”

“Oh no!” says Tea, looking stricken. “You gave him bacon? Sheep don’t eat bacon.”

“Well, neither do I. He didn’t eat it, though; he just sorta played with it. Then Tripod ate it.” Tripod is a three-legged cat here who has run of the place. He hangs out in the control room and listens while we work. “Now Tripod likes the lamb.”

Leslie looks at me from her hay bale. “That’s not cool. Bacon’s bad news.”

“Tripod thought it was pretty good news.” The lamb hops off my lap to play with the other lamb in the straw.

“Freeing lab animals is harder than you’d think,” says Tea. “I’ve looked into it.”

“We could free some farm animals,” I suggest. Tea looks thoughtfully at the calves. “Can I book a crime?” She nods. “I wanna pull off something… complicated… that would hurt mean people and help nice ones. Or Robin Hood money from somewhere bad to somewhere good.” I think. “And it’d take place in the Everglades.”

Dave looks at me. “I want in.”

“No dice, you already got your murder.” The lamb comes ambling back, so I pick it up and put it on my lap.

“I think my murder could play a role in your grander scheme,” he says.

“Oh, you wanna be under my auspices? Okay. What’re your qualifications? You were an owl keeper, right? That could come in handy.”

One summer, Dave and I worked at the bird sanctuary on the island. My job was great: I took little kid campers on hikes and taught them how to make herbal mosquito repellant, I fed orphaned baby foxes, raccoons and sparrow hawks. Dave’s job was killing mice and feeding them to the owl. The mice were cute and frightened and the owl was huge and very scary: blind in one eye and really pissed-off. It lived in a smelly pen far away from all the other animals. Dave hated his job, though he can now do excellent impressions of a sweet mouse about to die and an angry owl about to eat it. “Tea, Dave could help you free owls before he killed his person—”

Читать дальше

status quo

status quo