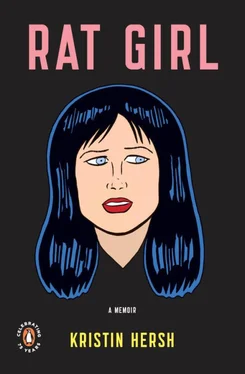

And if we ever get a good take of this song, there are a dozen more waiting, just as intense as this one. Ivo didn’t choose any of our fun songs for this record—the country-punk ones that are such a relief to play. Probably ’cause he’s English. “Country” isn’t his country. I was cool with that at the time, but now I’m realizing that every song on this record is gonna hurt and hurt bad.

I know how lucky we are to be here. I know how few bands ever get to this point. I remember all the work we did to earn this opportunity, how many years of practice and playing out. I know a lot of money is at stake and a lot of people are relying on me; I know our futures depend on the performances we capture now ; I know, I know. But this is like being trapped on a roller coaster.

’Cause even when a take is dead, I’m not—the song grabs me as it races past, like “Fish” did at the video shoot, thrusting shapes and colors and memories in my face. And because of the baby, I can’t disappear, can’t hide. I have to sit through every single goddamn note. I can only describe the effect as… anguish.

If I were a crier, I’d be in tears.

catch

catch

catch a bullet in your teeth

But my bandmates are here and their presence is comforting. It’s their record, too. I gotta keep it together for them.

Technically, we’re sitting in a circle facing each other, because that’s how we said we prefer to work, but we’re so far apart, it doesn’t matter. I can’t watch anybody else’s hands ’cause I can’t see them. And Dave isn’t even here. He’s in an isolation booth behind glass. Our amps are in other isolation booths, behind more glass, so there’s no actual sound in the room, no pulsing energy—just cold measuring. The record is supposed to sound live, like the demos, but this feels more like an operation than a show: clinical and cruel. Guts as plain old organs.

I don’t like science anymore , I think, I can’t like it — we’re chaos people. I want my art back.

The studio and control room are both enormous, full of more shining glass and that clean polished wood that’s everywhere here. The carpet is plush and elegant. It’s… someone else’s world. We don’t belong here.

We can’t even talk to each other ’cause I’m the only one with a mic. I whisper into my bandmates’ headphones, “ I don’t like fancy ,” and they shake their heads mournfully at me.

rat

rat

it occurred to me that someone might not understand our world

Our poor producer hasn’t stopped running around the studio listening for a “ booze ” since we started recording seven hours ago. He’s really hyper. Ivo sent Gil to us, having made the match himself. “Gil’s a good one,” he said. And Gil does seem like a good one; we all feel sorry for him, he’s so frustrated. He came all the way here from Liverpool, just to pace and sweat. We blame oursleves.

“I hear a booze , I hear a booze ! Do you hear a booze ?” he chants, racing around the airless studio, running his hands through his curly brown hair. We hold our instruments, wide-eyed, hands over the strings to keep them quiet, and watch Gil run back and forth.

When he bends over to look behind an amp, his glasses fall off. Swearing, he dives after them, freezes and stares into a corner, then turns to look at us. We stare back blankly. It’s like watching a cat chase a mouse, except that I’ve heard of mice. Booze is studio lingo with which I’m unfamiliar. Gil uses a lot of words we don’t know. “Is that it?” he asks no one in particular. “Is that the booze ?”

Finally, Leslie says. “Gil, we don’t know what a ‘booze’ is. ”

“ A booze, a booze ,” he cries frantically, testing cords and inputs and tapping microphones.

The assistant engineer, a young American man who came with the studio, follows him through the room, looking sheepish. “I think he’s hearing a buzz,” he says quietly to Leslie.

Her face lights up. “Oh! I know what that is!”

“Gil’s speaking English ,” clarifies Dave into his snare mic from behind glass.

Gil is a lovely man, just a little keyed up. “Of course I’m hearing a booze , there is a booze ! Don’t you hear it?” He flicks a switch on the back of an amp, checking the grounding, and we hear a snapping sound. “Aaah!” Gil yells, jumping backwards and sticking his finger in his mouth. “Another fucking shock!” he yells through his finger. “What the fuck’s the matter with this country? It’s been shocking me since the bloody plane landed! I wore me jumper and me pumps today, and I’m still getting shocked!” Leslie shoots me a look.

Tea looks deeply confused. “But you aren’t wearing a dress, Gil,” she says carefully. “ Or high heels…”

Gil looks at her, his finger still in his mouth, then he grabs a fistful of his sweater and says angrily, “ This is a jumper!” Pointing at his sneakers, he growls, “ These are pumps!”

“Gil’s speaking English ,” whispers Dave into our headphones.

By midnight, the buzz is gone, one song is done, and the workday officially ends. I yelled all day long. It felt… unkind.

What we did was, we took the song apart, played each piece separately, then stuck the pieces back together. In my opinion, it didn’t work. We’d torn the song’s limbs off, sewed them back on and then asked it to walk around the room. Of course, there’s no song left anymore; we killed it. It’s just a corpse—a neat, clean, sterile corpse—and corpses can’t walk.

I crawl upstairs to my wooden room and run a bath, trying to wash off this day. Dirty and clean are confusing me. Some clean is seeming dirty and some dirty is clearly clean:

A living song is dirty, a dead one clean.

Art is dirty, science clean.

Cities are dirty, nature is clean.

Crazy is dirty, health is clean.

Us poor people are dirty but pure of heart, and rich people are clean on the outside but so dirty where it counts that they hoard money they don’t need. Is that right?

This all seems true, but there’s something wrong with it.

My belly dances in the water. Tiny heels and fists push my skin around. What an adorable monster . I stay in the tub for hours. The water gets cold.

I don’t know if I’ve let music down or music’s let me down. Whatever.

I decide this is no place for a baby. With this thought, I choose the baby over music, and water becomes my friend again. Somehow, this bath washes off all my song tattoos.

some catch flies

some catch flies

Gil’s wife is as pregnant as I am, back in Liverpool, so Gil and I talk baby together at breakfast. While we talk, the chef fusses around us with an angry smile and then leaves to go bang metal things together in the kitchen. “Apparently, babies’re very small,” says Gil, staring into the distance. “And noisy.”

He’s afraid his wife’ll go into labor while we’re making this record. “I’m not usually this nervous,” he says, cleaning his glasses with a shaky hand. “Every time the phone rings, I nearly jump out of me skin.” He glances at my protruding belly, pressed against the table, and his pale face gets a little paler. “And you aren’t making me feel any better.”

Читать дальше

catch

catch